Kalamazoo embraces preapproved plans, zoning reform to turn vacant lots into homes

Several national housing-related organizations have applauded Kalamazoo’s preapproved housing program. The National Association of Home Builders highlighted the city’s approach to filling lots in a report about preapproved housing. Here's a look at how the program is going.

KALAMAZOO ― Kalamazoo zoning ordinances kept people from building homes on vacant lots in the city’s historic neighborhoods. So city leaders changed the rules.

Now, anyone interested in building on those lots can gain easy access to a fistful of permits and the professionally created plans of a house guaranteed to sail through the building process.

Sharilyn Parsons

What’s more, the city figured out how to use its lots to not only increase housing, but increase it exponentially via multifamily residences designed to fit the character and needs of the city’s neighborhoods.

The efforts fulfil several high-priority action steps recommended in the 2022 Kalamazoo County Housing Plan by the W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, commissioned by the Kalamazoo County Board of Commissioners.

The city’s efforts will bear tangible fruit in the shape of new housing cropping on vacant lots, says Sharilyn Parsons, Community Development Manager for the City of Kalamazoo, who oversees the city’s housing strategy.

“All the neighborhoods want more housing,” Parsons says. “Our land use strategy is, if it’s buildable, we’re ultimately going to build.”

Defining the need

The city and county have attacked the lack of housing on multiple fronts for several years. Thanks to the 2022 “Homes for All” millage, the county has allocated more than $26 million to housing development and supportive services and funded at least 1,400 new housing units, with 800 of those occupied, under construction, or breaking ground soon.

Most of those projects are either apartment-style residences ― including low-income apartments, senior housing, and a planned hotel conversion into affordable rental units ― or single-family houses outside the city.

The city itself, as part of its goals set in the “Imagine Kalamazoo 2025” master plan approved in 2017, has invested more than $200 million toward the development and preservation of housing. Most of that, too, has focused on projects that don’t address the at least 150 vacant city residential lots owned by the Kalamazoo County Land Bank, plus other lots owned by the city.

That leaves a lot of lots in Kalamazoo currently sitting vacant.

On North Rose Street, a newly built home fills a formerly vacant lot, thanks to a collaboration between the City of Kalamazoo, Kalamazoo Neighborhood Housing Services, the Home Builders Association of Western Michigan, and LISC.

Filling lots with homes bolsters neighborhood pride and safety, increases tax revenue for the city, and builds density that supports walkability crucial to urban life.

But construction on vacant lots falls short of a perfect quick-fix housing solution. Detached single-family homes are costly to build, live in, and repair, and communities can meet more needs more quickly by focusing on other types of housing.

Still, buyers and neighborhoods want houses. The Upjohn Institute said that of the 7,750 new housing units Kalamazoo needs by 2030 more than 1,000 should be urban and urban-center single-family detached homes. The city also needs another 550 single-family attached units, such as duplexes, according to the report.

When Kimberly Whittaker was looking for a home during the pandemic, the market was saturated with low-end housing.

“They were like sharks,” she says. “They was just selling anything and expecting people to buy it.”

Now, she and a handful of neighbors live in new homes ― not perfect, but nice, she says ― that line Burr Oak Street thanks to the city’s collaboration with KNHS. The home where her grandkids can come visit is a much better use of land than a vacant lot, Whittaker says.

“Use up the space, if it’s available, to build more houses, definitely,” she says. “Provide the opportunity for people that wouldn’t otherwise have it.”

Changing rules, making plans

To meet that need, Kalamazoo officials several years ago resolved to boost the city’s efforts to fill vacant lots.

They quickly realized the city’s own rules kept people from building. Zoning ordinances placed the majority of lots off-limits for home construction without complicated requests for variances. Many city lots, at only 30-some feet wide, were deemed too small to hold a house. Others weren’t zoned for a home at all.

“We looked at it and said, all right, what barriers can we change?” Parsons says.

The city began overhauling its zoning and code, consulting with neighborhoods along the way. After more than five years of work, the city has adjusted its zoning requirements to open most city residential lots to new home construction.

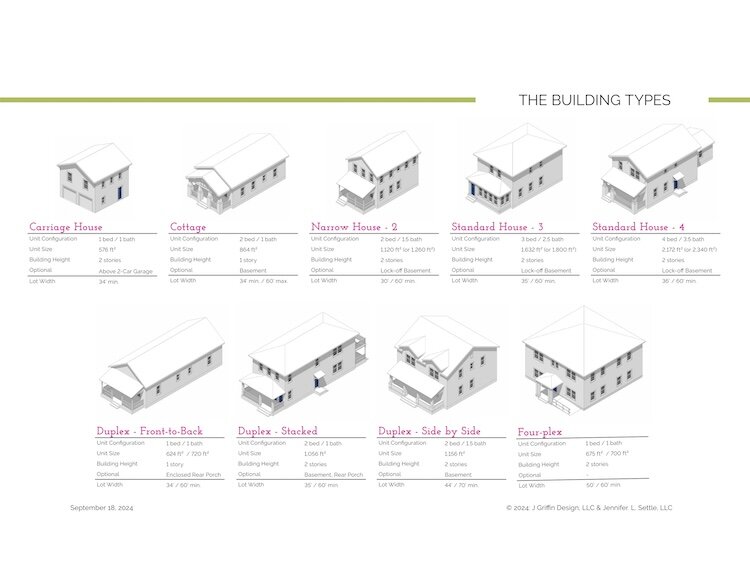

Many of those lots are pretty skinny, Parsons acknowledges. That’s why, when the city created a catalog of preapproved housing plans, it included a narrow house option that can fit on a lot only 30 feet wide and 60 feet deep.

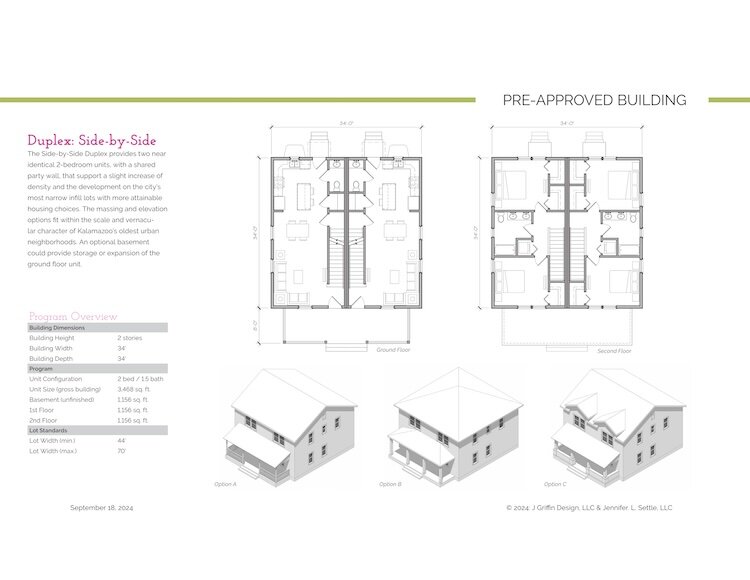

The catalog’s offering of eight house layouts is “meant to be a plug-and-play system,” Parsons says. The city enlisted a team of local architects to create plans for homes that meet all local codes and fit Kalamazoo neighborhoods’ aesthetics. The plans have the OK of all city departments related to home construction, so builders and prospective owners know they aren’t in for surprises and delays during the building process.

Where once a vacant lot meant unused city space, a newly built home now gives pride of ownership to Kalamazoo resident Kimberly Whittaker.

Like other cities using preapproved house plans to fill vacant lots, Kalamazoo saw the relatively new strategy as a way to get people into new homes quicker.

The city has bundled the permits associated with its preapproved designs and provides them alongside the professionally designed, detailed plans. The interested party pays only for the permit bundle. Having permits and an approved design in hand up front saves the builder from several layers of delays normally associated with a building approval process.

“You don’t have to get special permits. You don’t have to get special uses. You don’t have to get variances,” Parsons says. “It’s been preapproved by the city, and it’s ready to rock and roll.”

‘Missing middle housing’

The city has already seen its lots begin to fill thanks to a partnership between the city and Kalamazoo Neighborhood Housing Services, which, in cooperation with the Home Builders Association of Western Michigan and the Local Initiatives Support Corporation, facilitated the new construction of 48 new, affordable homes in city neighborhoods through the Kalamazoo Attainable Homes Partnership.

Now the city has turned its efforts to promoting its catalog of preapproved plans to help other people effectively build up neighborhoods by building on vacant lots.

In 2022, the city and KNHS unveiled a home based on one of the plans now in its catalog. At the intersection of Wall Street and South Rose Street, the building houses two families in a stacked duplex format that looks like any other single-family house on its street.

Just behind the home, a carriage house, also now in the catalog, houses a 576-square-foot apartment unit above a two-car garage.

The city intentionally included plans for what’s often called “missing middle housing” ― homes for two to five families in one building. In the city’s catalog, that includes front-to-back, stacked, and side-by-side duplexes and a fourplex. All are designed to fit the scale and form of city neighborhoods, using the look and footprint of a standard house to provide living space for more than one family.

Realtors say homebuyers prefer single-family homes. But in the next few years, people looking for homes in Kalamazoo are likely to prefer smaller, more economical housing options such as duplexes and other attached units, according to the Upjohn Institute report.

Multi-family units wouldn’t have been allowed in Kalamazoo neighborhoods under old rules. The city’s zoning overhaul changed that. In some cases, lots also allow for a second unit, such as the over-garage apartment. A national trend supports allowing such secondary buildings, commonly called Accessory Dwelling Units.

Nationally, new construction of multi-family homes screeched almost to a standstill since the 2009 housing recession. But, as housing experts advocate for zoning changes like Kalamazoo’s that allow more multi-family homes, cities across the country are embracing missing middle housing as an equitable fix for their housing woes.

“You’re increasing the density. You’re increasing the amount of people who live there. But you’re doing it very gently,” Parsons says. “You’re doing it in a way that doesn’t change the aesthetic or the fabric of the neighborhood at all.”

Some of the pre-appoved plans from the CIty of Kalamazoo

‘Build your dream’

City officials did not restrict use of the preapproved homes, freeing purchasers to live in one part of a duplex and rent out the other or use it for multigenerational housing. The city commissioned three plan types ― “good, better, and best,” Parsons calls them ― for each home in the catalog.

“We have a plan for whatever your end goal is for that house,” Parsons says, “so you can really manage costs and potentially build your dream.”

The city estimates its preapproved houses will fit into a wide range of budgets, with costs dependent on market costs of materials and labor. Recently imposed tariffs on imported goods such as the Canadian softwood lumber largely sourced from Canada could substantially raise prices for new home buyers.

All the more reason to offer preapproved plans to expedite the process for builders for whom every delay costs money, Parsons says.

Several national housing-related organizations, including the Congress for New Urbanism and Strong Towns, applauded Kalamazoo’s preapproved housing program. The National Association of Home Builders highlighted the city’s approach to filling lots in a May report about preapproved housing.

Parsons gets a lot of emails and phone calls from other communities asking about Kalamazoo’s model ― one that expands the definition of who can contribute to fixing the housing crisis, she says. With the city’s help, an everyday person can fill a lot and create housing, for themselves and maybe for someone else, too.

“Certain strategies require a professional to execute that strategy,” Parsons says. “In this model, everybody could be a solution.”

This story is part of Southwest Michigan Journalism Collaborative’s coverage of quality-of-life issues and equitable community development. SWMJC is a group of 12 regional organizations dedicated to strengthening local journalism. Visit swmichjournalism.com to learn more.

Find out more in this video created by Southwest Michigan Journalism Collaborative partner Public Media Network.