Uncovering Adverse Childhood Experiences and trauma-informed care intervention helps children thrive

The ACE scoring method is illuminating the relationship between stresses that children face that lead to public health problems later in life. Awareness of those connections is growing in Battle Creek and elsewhere in Calhoun County.

This article is part of a solutions-focused youth mental health reporting series of Southwest Michigan Journalism Collaborative, a group of 12 regional organizations dedicated to strengthening local journalism and reporting on successful responses to social problems. This story is funded by the Solutions Journalism Network.

Para leer este articulo en español dale click aqui.

Growing up, Kaypree Taylor knew he didn’t have many of the same advantages as his peers.

Taylor was 27 when he finally learned that there was a reason with a name for the “acting out” he did in elementary and middle school and the cloak of invisibility he used to buffer feelings of inadequacies because he didn’t have what others had.

That name – ACE (Adverse Childhood Experiences) – revealed itself to him while working for Summit Pointe in Battle Creek.

“We did a survey with some of the students from Battle Creek Central High School and we were told the adults could take the survey too. That’s when I got clarification,” says Taylor, now 31, who grew up in the city’s Washington Heights neighborhood. “It gave me a sense of belonging to where I felt like I was part of a group of other people who were aware of what I was going through.”

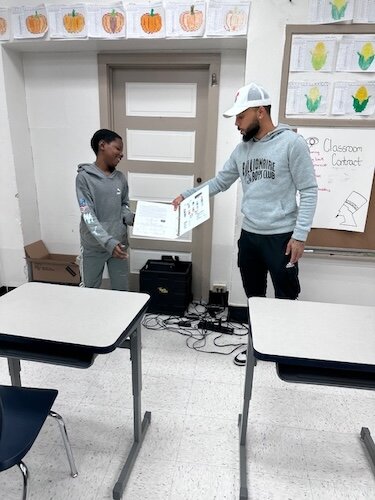

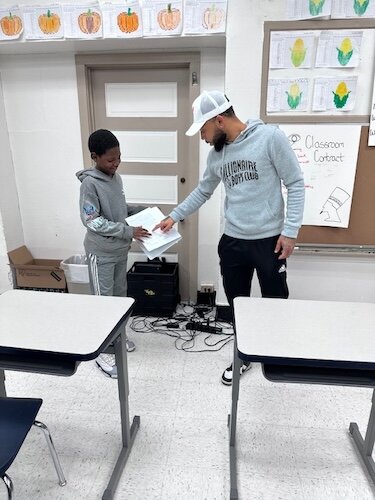

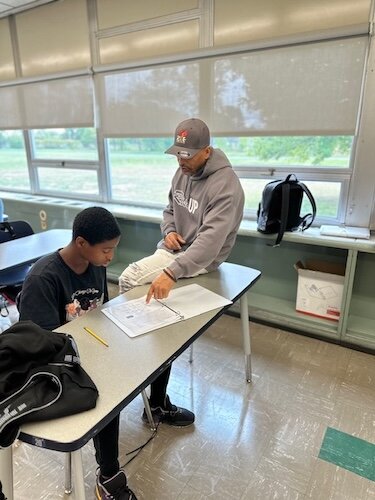

Kaypree Taylor, a R.I.S.E. staff member, works with a youth on their reading skills and assists other youth participants during classroom time.

His ACE score was nine based on his survey responses. Individual ACE scores are assigned a number between 0-10 based on answers to 10 questions that focus on adverse experiences during childhood. The higher your ACE score the higher your statistical chance of suffering from a range of psychological and medical problems.

The ACE scoring method is illuminating the relationship between stresses that children face that lead to public health problems later in life and the importance of preventing ACEs before they happen, a cause being promoted by a number of organizations across the region.

The scoring was created after the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Kaiser Permanente collaborated on a study that was designed to examine the relationships among 10 childhood stressors and a variety of health and social problems. The study demonstrated how abuse, neglect, witnessing domestic violence, and childhood exposure to household dysfunctions are common and highly interrelated, according to the American Journal of Preventative Medicine.

What the ACE Score Means

The scoring has identified a powerful relationship between Adverse Childhood Experiences and the risk of public health problems and it has raised policymakers’ and legislators’ awareness of the childhood origins of those problems, according to the American Journal of Preventive Medicine.

Kaypree Taylor, a R.I.S.E. staff member, works with a youth on their reading skills and assists other youth participants during classroom time.

However, the article goes on to say that questions from the ACE study cannot fully assess the frequency, intensity, or chronicity of exposure to an Adverse Childhood Experience or account for sex differences or differences in the timing of exposure.

As a result, “projecting the risk of health or social outcomes based on any individual’s ACE score by applying grouped (or average) risk observed in epidemiologic studies can lead to significant underestimation or overestimation of actual risk; thus, the ACE score is not suitable for screening individuals and assigning risk for use in decision making about need for services or treatment,” says the AJPM article.

The real-life effects of Adverse Childhood Experiences

While in elementary school, Taylor got in trouble a lot and would be angered by the “littlest thing.” His elementary school principal allowed him to lie down in his office and take a nap as a way for him to calm down.

“When he asked me why I got angry, I told him I didn’t have a male role model in my life,” says Taylor, whose father was killed when he was 3 years old.

He suffered another loss when one of his brothers killed himself shortly after his father died. His mother worked multiple jobs to support him and his seven brothers and sisters, leaving her little time to address the social and emotional needs of her children.

While working for the 21st Century program funded through the Battle Creek Public Schools, his first job out of college, Taylor interacted with high school students who were experiencing some of the same things he had experienced as a youth.

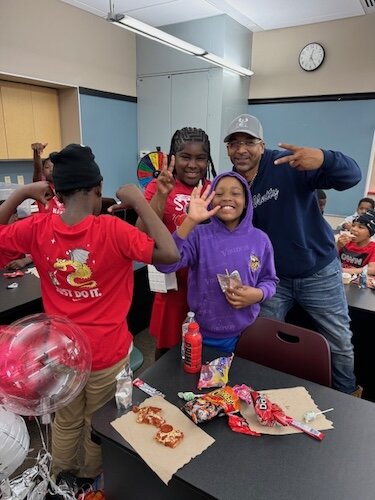

Damon Brown, R.I.S.E. founder, enjoying a lunch break with youth participants.

“I could empathize with them and let them know that they weren’t alone,” he says.

He made a point of learning about community programs in Battle Creek that offered a deeper dive into what young people were going through by seeking out resources in the community. He eventually reached out to Damon Brown, founder and CEO of RISE (Re-Integration to Support and Empower), one of a number of local groups working with ACEs scoring.

Battle Creek and Calhoun County also have gone into various parts of the community with awareness training on ACEs, facilitating screenings of a video about ACEs called “Resilience”, expanding its availability through acquiring additional licenses, and being part of the Master Training Program of the Michigan ACE Initiative, wrote Rick Murdock, the Michigan ACE Initiative Grant Coordinator in his blog in 2018.

The United Way of South Central Michigan also is actively engaged in providing resources about ACEs.

“These critical health and social consequences highlight the importance of preventing ACEs before they happen,” the organization’s website asserts. “Healthy school, community, and home environments are necessary for preventing children from experiencing ACEs and appropriately supporting students living with chronic stress.”

Validating the trauma

Among RISE’s pillars of success is education done through programming for youth that provides extracurricular learning that keeps children engaged and in a safe environment after school and over the weekend, Brown says.

“Aware that many local youth have challenging home lives — typically the children have high Adverse Childhood Experience scores — all RISE activities are crafted with trauma-informed care as the foundational objective,” he says.

ACE scoring is the foundation that this programming is based on, says Brown who has experienced childhood traumas; he was raised in challenging circumstances that he believes led to his sentence of 12 years in prison for selling crack cocaine after he was arrested during a federal drug sweep in 2001.

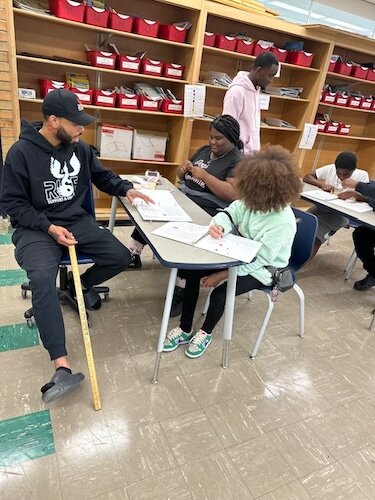

Damon Brown, founder of R.I.S.E., spends some one-on-one time with a youth participant.

He and his staff of six, which now includes Taylor, meet regularly in group settings or in one-on-one sessions with some of the 106 children and 50 adults currently served by RISE.

About 64% of adults in the United States reported they had experienced at least one type of ACE before age 18. Nearly one in six (17.3%) adults reported they had experienced four or more types of ACEs, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In Michigan, 68 percent of adults reported having one or more ACEs and 63 percent of high school students in the state reported one or more ACEs, according to the MI ACE data dashboard. The dashboard MI ACE Data Dashboard was unveiled in 2022 by its creators, the Michigan Public Health Initiative (MPHI) Center for Strategic Health Partnerships, to launch the statewide MI ACE Data Dashboard that would measure and track ACEs in Michigan.

“The kids are actually going through these ACEs in real time and the adults already have experienced it. For the adults, it’s more of a healing piece, being able to acknowledge and validate what’s going on and recognize what they’re going through using a trauma-informed approach,” says Brown, who is Master Trained in ACEs. “We are finding ways to address each of the 10 ACEs questions.”

On-Site ACES Resources in Schools

In addition to the services offered at RISE, the organization also has an on-site presence at Northwestern Middle School and Ann J. Kellogg and Verona Elementary schools through a contract with BCPS. RISE’s six staff members are paired off in dedicated classrooms during school hours Monday through Friday to work with children experiencing learning or behavioral issues.

Northwestern also offers a RISE elective for students in a dedicated classroom to supplement their in-school learning with the organization’s ACEs foundation model. Northwestern ranks 517 out of 689 middle schools in Michigan, according to U.S. News & World Report. Some 82% of the students enrolled there come from economically disadvantaged circumstances.

The contract and funding from the W.K. Kellogg Foundation, the Binda Foundation, and the United Way of South Central Michigan offset the cost of operating the in-school component.

In real-time, RISE staff can step in as buffers when teachers or administrators request this intervention to help youth understand what they might be going through. Brown says there’s a tendency for the youth to blame themselves for negative things going on at home that they have no control over.

“We are educating and giving them coping mechanisms and constantly drilling into their heads that what they’re dealing with is not their fault,” Brown says. “The things a child goes through has everything to do with the parents. We look at who are their parents; are they being raised by a single parent or are they in foster care? Do they have rides to school? Are they being fed in the morning? Do they have clean clothes? Are mom and dad drug addicts? These are the things they have no control over.”

Data points to success

In a 2023-24 data report presented by RISE to leadership with BCPS, the organization’s efforts are showing some successes.

Of the 24 students at Verona Elementary who participated in the RISE program during the 2023-24 school year, 11 of them increased their NWEA (Northwestern Evaluation Association) scores in math, and16 students (67%) improved their NWEA scores in ELA (English Language Arts) during the spring test.

There also was an increase in attendance rates from 90% to 97%.

“Attendance is a critical factor in ensuring student success, as regular attendance is closely linked to improved academic performance and positive behavior,” says the end-of-school-year report.

Academically, 12 of the 21 participating students at Ann J. Kellogg increased their spring NWEA scores in ELA, and 11 students improved their scores in math. Attendance rates for all 21 increased from 92% to 100%. However, the report says, “it is important to note that 17 students experienced an increase in discipline incidents compared to the previous school year.”

At Northwestern Middle School, 20 of the 59 students participating in the RISE program met the district attendance goal. Despite the attendance challenges, 23 students earned a “C” or better in their English class, and 26 students achieved a “C” or better in their math class.

“These academic successes demonstrate the resilience and determination of the students, as well as the effectiveness of the academic support provided by the RISE program,” the report says.

Based on these outcomes, RISE was asked to provide a version of this in-school programming at the Douglass Community Association in Kalamazoo. RISE staff are on-site from 5-7 p.m. on Thursdays.

Generational Trauma Overcome with Empathy

“Many of the kids we work with have parents who never grew out of their ACEs,” Brown says. “We keep telling them that what they’re going through has everything to do with the adults in their lives. These kids are smart. We have to talk to them and prepare them to deal with their own ACEs much earlier.”

Youth and adults served by RISE in the ACEs space are assessed through a social-emotional lens to see what areas could be strengthened. The youth and adults engage separately in a 12-step program focused on decision-making, regulating their emotions, making positive choices, and understanding the impact ACEs has on their lives.

“We use empathy and active listening. We create a safe space for them to be able to share and process emotions and acknowledge the different things they’ve been through,” Brown says. “First, you’ve got to get people talking about it and feeling comfortable.”

They are encouraged to focus on mindfulness and self-care that includes practicing yoga or meditation and engaging in creative activities involving art or music. Brown says this helps to re-frame negative beliefs and self-talk stemming from ACEs which present differently in adults and youth.

“Some people think that if their ACEs score is a 10 they’re doomed. I was able to find enough resilience in my environment to pick myself up by the bootstraps if you will,” Brown says. “It’s about building resilience and being able to adapt. We’re helping people to create those coping and problem-solving skills and we can also hook them up with other resources in the community.”