Turtle dogs: How South Carolina bird dogs help count Michigan turtles

Boykin Spaniels can find the turtles that elude people searching in the undergrowth.

Taking a natural resources inventory isn’t as easy as checking off the number of boxes on a warehouse shelf.

Documenting elusive butterflies or rare plants can mean slogging through mud and brambles hoping to discover things that are often, by nature’s design, very hard to spot.

But Michigan biologists tasked with tracking Eastern box turtles are getting a helping hand, from a former English teacher who has trained his troupe of hunting dogs to sniff out turtles on the move.

Once they find them, the dogs gently, gently pick up the turtles and deliver them to be counted.

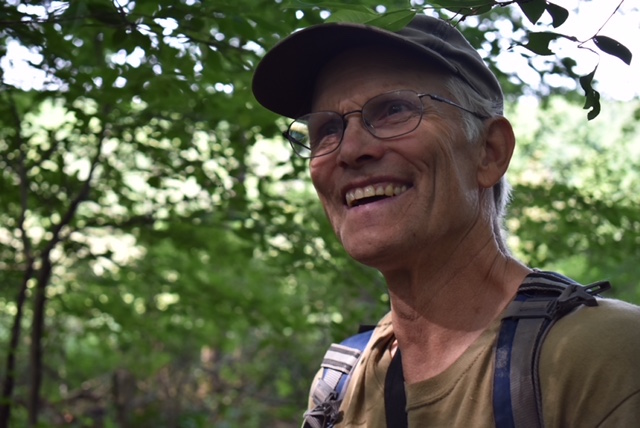

John Rucker travels the country with his Boykin Spaniels, a breed designated the state dog of South Carolina, where it is prized for hunting waterfowl.

“I’d been hearing about John and his dogs for years from his work with box turtles at Fort Custer (Recreation Area),” says Nate Fuller, Conservation and Stewardship Director for Southwest Michigan Land Conservancy in Galesburg.

At Fort Custer, Michigan State University and the Michigan Department of Natural Resources were studying effects of prescription burns on the turtles.

At the Land Conservancy’s preserves, biologists hope to get an idea of how many turtles are on the sites to establish a baseline. Later studies can show whether the population is growing or dwindling. But getting a handle on the number of turtles was proving to be tough.

Then “this past winter a friend who works for Nottawaseppi Band contacted me to see if I was interested in pooling resources,” Fuller says.

Together with the Pokagon Band and Pierce Cedar Creek Institute, Southwest Michigan Land Conservancy got together more than 10 days of work, enough to make it worth Rucker’s drive from his home in Montana.

On June 25 Rucker arrived at the land conservancy’s 189-acre Portman Nature Preserve in Van Buren County, where he worked with four mature dogs — Rooster, Jenny-Wren, Jay-Bird, and Mink — all 10-year-olds with extensive turtle hunting experience.

The next day, two-year-old Scamp was added to the group for an infusion of youthful energy.

“Scamp roamed large circles around the group while Rooster got tired and kept a much smaller orbit around John,” Fuller says. “Mink was the most thorough, determinedly tracking turtles that had even burrowed under logs.”

A team of three dogs visited Bow in the Clouds Preserve in Kalamazoo as well.

It’s usual for the team of seven dogs to work in rotation, with the old pros teaming up with younger dogs to teach them the art of finding the well-camouflaged turtles, then gentling carrying them to Rucker. If the dogs find a turtle too big to carry, they will insistently bark until a person comes to praise the dog’s find, Fuller says.

Each turtle is released, unharmed after researchers document information and photograph its shell. The markings of each turtle shell are unique, so the photos serve as mug shots of the population, Fuller says.

The dogs are far more efficient at finding the turtles than the human field researchers are. “At Portman, the dogs found more turtles in two mornings of work than we found in two years,” Fuller says.

That’s because the dogs can sniff out the trails of turtles on the move, says Alicia Ihnken, stewardship analyst for the MDNR in Lansing.

“Without the dogs, it’s all just (done by) sight,” Ihnken says. Since 2012 Ihnken has worked with a team to document the turtles at Fort Custer Recreation Area near Battle Creek.

“That first year (before the dogs) we were just wandering around looking for turtles, Ihnken says. Through networking with other turtle researchers, Ihnken learned about Rucker and his dogs.

“Everyone who does terrestrial turtle research uses John,” she says.

Rucker travels in a custom van rigged with individual kennels for each dog, and he sleeps in a tent alongside the vehicle every night he’s on the road, Fuller says. He even brings outdoor kennels to house the dogs who are not working on a particular day.

“John makes an annual trek from Montana to the central-eastern U.S.,” Fuller says, which includes a regular job with a university studying turtles in Tennessee that takes up most of the month of May. He then travels all over the East and Midwest to where people have work for him and his dogs.

“He had stories of looking for turtles from just about everywhere except in the Southwest,” Fuller says, where big rattlesnakes pose too great a risk to the dogs.

Rucken’s first trip to Michigan came in 2013 when Ihnken’s group brought him in.

Southwest Michigan’s habitat created its own challenges that first year. The dogs, used to working in old growth forests where it was easy to maintain eye contact with their handler, were a little thrown by Michigan’s dense shrubs and scrubby understory, Ihnken says.

“The dogs couldn’t navigate the same way they did down South,” she says. “It’s like the difference between a person walking on a trail or off trail.”

The Boykins quickly adapted.

At Portman this year, dogs and observers alike struggled to move through the dense vegetation and deep muck.

“As we wallowed through the muck and mire, John would say ‘This is the Major Leagues! Can you believe what these dogs are doing! This isn’t easy stuff – this is Major League ball going on here!'”

Ihnken said the turtles are easiest to find during nesting season, when they tend to congregate in sandy areas outside of the deep forest and when they are on the move. The dogs are keying in on scent trail laid down as the turtles crawl. If turtles haven’t moved, the dogs can walk right past them without scenting or seeing them, Ihnken says.

“But as soon as they catch a whiff, they are remarkable,” she says. “One of the dogs went into a shrub, working, working, working—” and eventually came out victorious with a tiny 2-year-old turtle in its mouth.

That was the first documentation of a young turtle at Fort Custer, proof that the turtles at Fort Custer are reproducing, she says.

It was very welcome news.

Box turtle populations are declining across the state, Fuller says. One problem, people are collecting from the wild for pets, especially for certain species like Blanding’s, box, and spotted turtles, Fuller says.

But nest predation is the biggest problem.

Turtle eggs are incubated by sunshine, he explains, so nest site selection is limited to areas with loose sandy soil and bright sunshine.

“Unfortunately invasive brush often shades out good potential nest sites and the turtles are forced to concentrate nesting efforts,” Fuller says. “The nest predators, especially raccoons, can raid these areas like a buffet line.”

To help, the land conservancy is clearing brush on south-facing slopes with sandy soils at some of its preserves, like Portman and Bow in the Clouds, to provide more nesting options.

“This way all the turtle eggs aren’t in one basket,” Fuller says.

Biologists also are exploring ways to deter predators. “So far it sounds like the only reliable option researchers have found to protect nesting areas is electric fencing, set high enough to allow turtles to go under it, but low enough to zap raccoons, foxes, skunks, opossums,” he says. “But we’ve been reluctant to put electric fencing out where we have high public visitation.”

Tracking the populations is one way to learn more about whether such efforts are helping, and in that the dogs have been key. But in the end, it’s all about much more than turtles or the dogs that find them, Fuller says.

As the land conservancy strives to protect and restore the biodiversity of its preserves, understanding the animals that are living there in the first place is a critical first step in making management decisions.

‘Eastern box turtles use a variety of habitats and are so long-lived they can serve as a barometer for how our preserves are doing for decades to come,” Fuller says.

“Our goal is that the preserves will be thriving sources of enjoyment for both people and turtles for many generations to come.”