The Fire Hub restaurant, a casino spinoff, feeds its customers and funds food pantry

What happens when you have too much food on one hand and people without enough food on the other. For FireKeepers the answer was a restaurant and food pantry combo.

As a chef and Vice President of Food and Beverage at FireKeepers Casino Hotel, Michael McFarlen was in a unique position to see the amount of food thrown away on a daily basis.

And McFarlen’s involvement with the South Central Food Bank of Michigan Inc., where he serves as president of the board, gave him a similarly unique view of the number of people in the community who face food insecurity.

Ongoing food waste juxtaposed with a landscape populated with people, many of whom who don’t know where their next meal is coming from, prompted McFarlen and FireKeepers leadership to develop a plan. They decided to renovate an old fire station to accommodate the Fire Hub Restaurant and Kendall Street Food Pantry which share space at Dickman Road and Kendall Street.

The restaurant occupies the front of the building and the food pantry is at the back.

While community service and outreach are not unique to casinos owned by Native American tribes, combining a restaurant and food pantry is, says Kathy George, Chief Executive Officer of FireKeepers.

“It really is unique,” George says. “A number of casinos do outreach, but we’re not aware of anyone who actually created a restaurant and food pantry directly.”

Guest feedback about the food and service at the Fire Hub has been overwhelmingly positive. It has earned 4.5 out of 5-star reviews on TripAdvisor with “excellent” and “very good” ratings. While George says the first year of operation was successful, she acknowledges that revenues were not quite what they were expected to be.

“Anytime you open a new restaurant, you just have to figure a way through that first year,” George says.

However, the Fire Hub and the food pantry exceeded initial expectations for much different reasons – the restaurant for its popularity and sustainability and the food pantry for the numbers of people it has been serving since its doors first opened.

McFarlen says projected numbers were between 65 and 70 households when the pantry began operating. That number quickly escalated to 100 on each distribution day – every Monday from 4-6 p.m. – which equates to between 375 to 400 households per month.

The money to operate the Fire Hub is a combination of $140,000 that comes from the tribe annually and from food and beverage revenue generated by the restaurant.

Proceeds from the Fire Hub have been given to nonprofits, including Safe Place and the Food Bank of South Central Michigan Inc. which recently received a check for $15,000. McFarlen says he’d like to be in a position to make even larger donations to area charities on a more frequent basis.

“We’re building a fiscally responsible business that takes profits and gives to nonprofits,” he says. “As we get more and more involved, we will give to many other charities and nonprofits.”

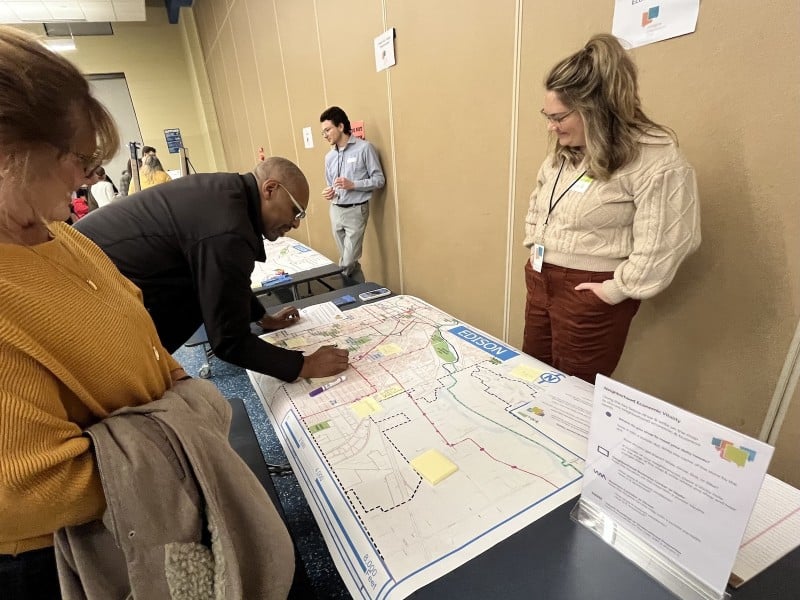

Robert Elchert, Community Impact Associate for United Way of the Battle Creek and Kalamazoo Region, says the Fire Hub is a great United Way partner because they apply their strengths and energy in specific ways to impact the community. He cites the Fire Hub’s hosting of United Way Pop Up Giving events and VolunBeer activities for their young leaders group as examples of this partnership.

“They support our work addressing food insecurity through the Kendall Street Food Pantry, in concert with the Food Bank of South Central Michigan. Partnerships like this deliver a vital return on community and social responsibility,” Elchert says. “From United Way’s perspective, Fire Hub models the kind of collaboration that can address the toughest needs vulnerable individuals and families are facing.”

Food pantry clients are limited to one visit per month. They are registered with the program, which gives food pantry volunteers the ability to track their shopping habits and the number of people in their families, in addition to notifying them about special distributions.

About 45 percent of people who come through only come through once, McFarlen says.

“We have people who need that one-time distribution to get back on track,” he says. “About 20 percent are people who make two or three visits. They’re not all from Battle Creek. Some of them work here, but live in Albion, Marshall, and Kalamazoo.”

Even though these people are employed, they continue to struggle, says Heather Mauney, director of Agency Relations for the Food Bank. In addition, she says, there is also a small number of people on a fixed income who are likely to always need their services and the services of others.

“We’ve seen a significant increase in households where one or both adults are working and they find themselves in some sort of crisis situation like an illness or car accident and they need our help,” Mauney says. “We get a lot of people who are not used to how the system works. We’re able to cater to people who are working, but still need a little help during the month,” she says. “The need has not decreased. If anything it has increased and shifted.”

The Kendall Street Food Pantry is the only one operated by the Food Bank of South Central Michigan which partners with more than 300 agencies in a service area that includes Barry, Branch, Calhoun, Hillsdale, Jackson, Kalamazoo, Lenawee, and St. Joseph counties. Heather Mauney, director of Agency Relations for the Food Bank, says it’s not common for food banks to operate food pantries.

“We cover a 5,000-square-mile service area and the logistics of overseeing and running a pantry 100 miles away in Lenawee doesn’t make sense,” Mauney says. “The opportunity presented itself with FireKeepers and we just really didn’t have a good reason to say no. It makes sense for us to operate it because it gives us an opportunity to try out and test new things before rolling them out.

“It is quite small compared to other pantries. Sometimes space can be a barrier for people who want to start a food pantry and we are able to show off how much we can do in a smaller space.”

From the outset, the food pantry was designed to be a “choice pantry” which allows individuals to come in and “shop” for whatever they want. Milk and meat are among the staples people ask for on a regular basis, so the shelves are fairly well-stocked with these items. In addition, there are canned goods, boxed meals, fruits and vegetables and a small selection of gluten-free and vegan items.

The pantry has the look and feel of a store with shelves that contain neatly arranged food products and shopping carts. “We wanted to take away the stigma and make it more like they’re going into a bodega or little store,” McFarlen says.

Mauney says across the industry more work has been done with to address the stigma of individuals needing food pantries. Her food bank is working with agencies across its service areas to make sure that those who come into a food pantry are treated with kindness.

Food to stock the Kendall Street Pantry shelves comes from a number of sources, including the United States Department of Agriculture; the Kellogg and Post companies; several large retail donors and stores; individual donors; and FireKeepers.

Remember that food that McFarlen says remains unused or untouched at the Casino and Hotel? Well, that food is packaged up and taken to the food bank which then distributes to its partner agencies.

“We purchased the equipment that is necessary to receive the proper licenses to flash-freeze food from the buffet and we make family trays out of them,” George says. “In addition to canned goods and fresh fruits and vegetables, we supplement them with family portions from the buffet.”

Last year, more than 14,000 pounds of frozen food from FireKeepers made its way into area food pantries through the Casino/Hotel’s participation in the Environmental Protection Agency’s Food Recovery Challenge. As part of the challenge, organizations pledge to improve their sustainable food management practices and report their results. The Food Recovery Challenge is part of EPA’s Sustainable Materials Management Program, which seeks to reduce the environmental impact of materials through their entire life cycle.

“We drop off about half a ton of food each month and the food bank decides where it goes,” McFarlen says. “The FRC gives you an idea of where you stand with other people trying to make an impact. For a small community that we’re in to make this kind of impact I could only imagine what they do in Los Angeles and New York.”

The prepared meals can be microwaved or boiled. But, McFarlen and his team also work with food pantry clients to show them how to prepare and cook fresh food, including vegetables that are donated by area farmers. This initiative came about after they learned that a lot of highly-nutrient, plant-based foods were being thrown out, particularly vegetables like rutabagas and kale.

“We identified a shortcoming where families in need were getting the food but didn’t know how to prepare or create a recipe that their family would eat,” he says.

The food bank and representatives with Michigan State University Extension Services partnered with McFarlen and his team to create recipes designed around what was being distributed. He says about 50 of these demonstrations happen each month throughout the Food Bank’s eight-county service area.

Another component of FireKeepers efforts to address food insecurity involves a greenhouse program with the goal of establishing free salad bars at area schools. A variety of lettuces, cucumbers, tomatoes, micro-greens, and other salad staples are being grown organically (without pesticides) at a greenhouse on land owned by the tribe under the watchful eye of an agricultural specialist and employees with the Casino/Hotel’s Groundskeepers crew.

“We looked at Battle Creek community schools and identified those schools with the highest number of students receiving free- or reduced-lunch. We looked at how we could tackle lunch programs and decided to put together a greenhouse program where we could put free salad bars into those schools,” McFarlen says.

The first harvest is expected to happen in about one week. On April 1, the first salad bar will open at Athens Schools.

Once the Community Garden is fully operational, McFarlen says he will rely on volunteers to augment the work required to make it sustainable. He anticipates getting support from casino employees, his team members, and individuals from the Food Bank.

McFarlen says the majority of the day-to-day work and execution of the plans to broaden the scope and reach of FireKeepers work to address food insecurity in the community is done by his team. “They have done an amazing job,” he says.

FireKeepers CEO George says it’s always been a priority of the tribe and FireKeepers to be good stewards of the community.

“The Casino and band are phenomenal people,” she says. “They have such a huge heart and want to continue to be great partners in the community.”