Step inside an award-winning library for people with disabilities

Roel Garcia shares what it's like to visit the Library for the Visually Impaired and Physically Disabled in Muskegon. Part of the Muskegon Area District Library, it is a fully functioning library specializing in additional services for people with disabilities.

A familiar feeling overtakes me upon entering the Library for the Visually Impaired and Physically Disabled in Muskegon. It is the soothing, calmness of thousands of books on shelves and the sweet aroma that only libraries and old bookstores exude. It is a warm feeling, and there is nothing quite like it.

The library, part of the Muskegon Area District Library, is a fully functioning library, complete with a children’s section, public computers, and many other materials. However, this library specializes in additional services for people with disabilities.

Last year, the National Library Service for the Blind and Print Disabled at the Library of Congress honored the Muskegon library with the Sub-regional Library/Advisory and Outreach Center of the Year Award.

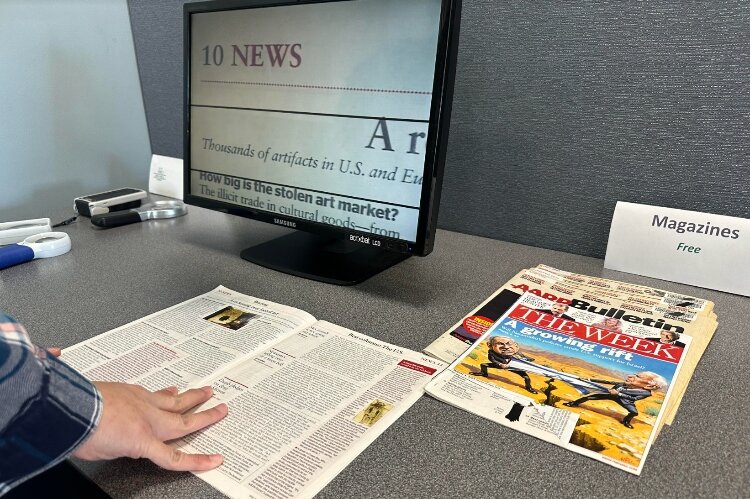

The library has a device that magnify images.

The library, with one full-time librarian and a part-time reader advisor, serves more than 940 patrons in Michigan’s Muskegon and Ottawa counties.

Among the library’s initiatives are a Senior Book Bin service, which delivers bins of large-print books to area senior organizations each month, and Phone-A-Story, a dial-in service that offers weekly recordings of poems, short stories and children’s stories.

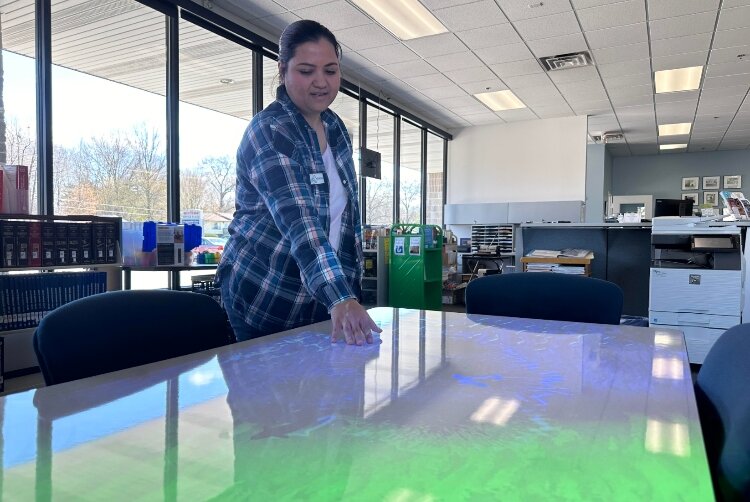

The library has an array of accessible technology for patrons, including closed-circuit televisions that magnify images, an optical character reader, a refreshable braille display, and an interactive game table that stimulates memory development in those with intellectual disabilities.

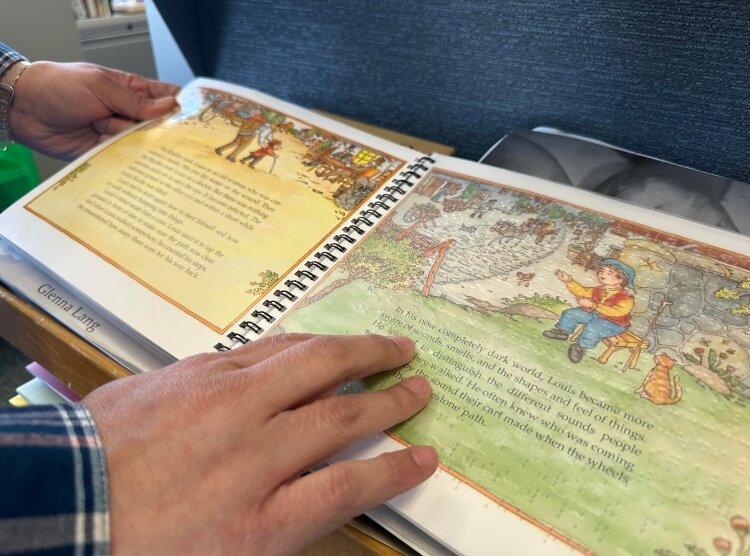

It offers a large collection of large-print books for people with low vision and the Talking Book Program for those with vision and physical disabilities.

“We try to help everybody who has a disability,” says Sax Mahoney, lead librarian for the Library for the Visually Impaired and Physically Disabled.

Librarian Sax Mahoney displays a digital player for the Talking Books program.

Huge selection of audiobooks

The library’s most popular offering is the Talking Book Program. This national program of nearly 120,000 audiobooks and dozens of audio magazines brings the world of books into the lives of people with disabilities.

About 900 residents from the library’s two-county area use the Talking Book Program, Mahoney says. Those who qualify cover a multitude of disabilities.

“The program is for someone who can’t read regular print or who has reading disabilities like dyslexia,” Mahoney says. “But it’s also for people who can’t hold a book. So if someone can see but if they have Parkinson’s or arthritis so that they can’t hold a book open, they would still qualify.”

Qualifying individuals are lent a Digital Standard Player that plays audiobooks. These machines can be adapted, depending on a person’s disability.

For example, some digital machines have a breath switch. This adaptation is for individuals who are missing limbs or who have dexterity problems and who cannot hold books open. People use puffs of air to work the machine. Similarly, some devices have pillow speakers for individuals who are bedridden.

The library carries a large collection of braille books.

Must qualify for program

Mahoney says those with hearing impairments also can get adaptive applications to assist with hearing the audiobooks. The digital players have an internal amplified speaker with connected headphones that plays the audiobooks very loudly.

“It is incredibly loud. To qualify for this is a separate application. (Applicants) must have the application signed by an audiologist,” Mahoney says.

To qualify for the Talking Book Program, individuals must first fill out an application. Part of the application requires an authority, such as a therapist, doctor, nurse, or social worker to verify that the applicant qualifies for the program, Mahoney says.

Once a person qualifies for the Talking Book Program, the process of receiving audiobooks begins. A digital player is sent to individuals. It has a slot where cartridges filled with downloaded audiobooks can be inserted.

“The cartridges are like empty flash drives. We put as many audiobooks as you request and we mail them to you,” Mahoney says.

Cartridges are mailed in thick, blue plastic containers. There is no time limit to how long a person can keep the cartridges. When the person finishes the audiobooks, cartridges are mailed back in the same blue containers. No postage is necessary.

Mahoney says that when setting up for receiving audiobooks, people can choose from a vast list of categories, genres, and authors. Audiobooks from those chosen genres will be sent out in the cartridges. People can add as many audiobooks per cartridge as they want.

Individuals qualifying for the Talking Books Program also are eligible for the BARD (Braille and Audio Reading Downloads) website. If users request BARD, they will receive a link to the website and they will need to add a username and password. They also can download the BARD app onto their smart device or phone.

“You log in and download books onto your device,” Mahoney says. “When you’re done listening to them, you can delete them.”

Braille eReaders can be lent out for those who can read Braille. Braille books can be downloaded onto them and people can read them on the go.

Library Assistant Syarifah Alhasni demonstrates Tovertafel (Dutch for Magic Table), an accessible library feature.

App lets you listen anywhere

Using the app on portable devices such as cell phones makes it easier to listen to books on the go because people don’t have to carry the larger digital reader with them.

For a voracious reader like myself, I enjoy having access to the BARD app on my Smartphone as well as the digital reader. When I am waiting at an appointment or on a bus, I can listen to a downloaded audiobook on my cell phone to pass the time. While at home, using the digital reader works because I can listen to audiobooks while doing tasks around the house.

Technology has created huge advancements in the Talking Book Program. The Talking Books Program began about a century ago. In the 1920s, records and record players were mailed out, Mahoney says. Over the years, record players and records transitioned to large cassette players and cassette tapes, and now audiobooks are on digital formats.

“(The program) started out as a program only for blind persons, then for low vision, then physical disabilities and more recently learning disabilities,” Mahoney says.

Audiobooks are added to the collection every week. There are books for children, teens and adults. More recently, audiobooks are available in a multitude of languages ranging from English to Spanish and French to Chinese.

“Since the program is nationwide, if you move, you can transfer to a library wherever you go,” Mahoney says.

The address for the Library for Visually-Impaired and Physically Disabled is 4845 Airline Road, Muskegon. The phone number is 231-737-6310.

To request information about applying to the Talking Books Program, email the library at lvpd@madl.org or go to www.madl.org/lvpd.

Photos by Shandra Martinez

This article is a part of the multi-year series Disability Inclusion, exploring the state of West Michigan’s growing disability community. The series is made possible through a partnership with Centers for Independent Living organizations across West Michigan.