Editor’s note: This story is part of Southwest Michigan Second Wave’s On the Ground Battle Creek series.

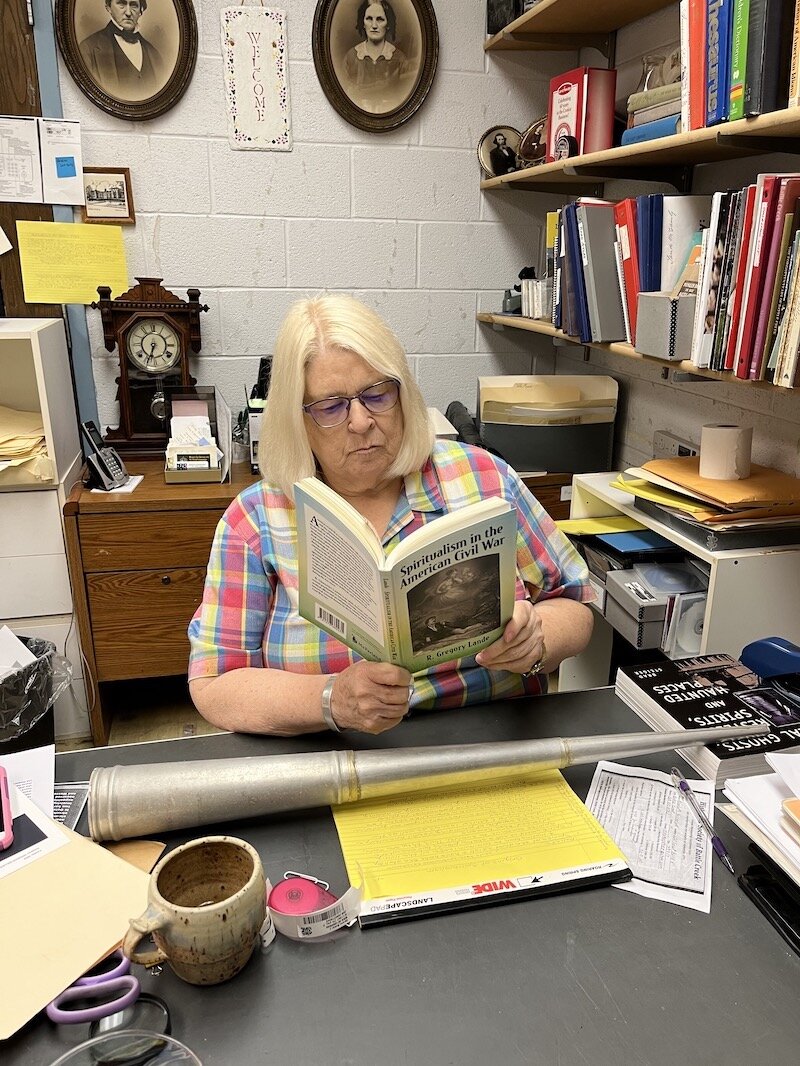

Corn flakes and spiritualism may not seem to have anything in common, but they do, says Jody Owens, a volunteer with the Battle Creek Historical Society.

She says Battle Creek gained renown from each in different ways. While corn flakes established Battle Creek’s place as a leader in the cereal industry, Owens says the spiritualist movement, which was founded on the belief that the dead were eager to communicate with the living, generated national attention for the city during the mid- to late-1800’s.

She will share her insights and the history she has learned about this movement during two sessions on Nov. 22 and Nov. 29 titled “The Origins of Spiritualism in Battle Creek.” Both sessions are part of Kellogg Community College’s Lifelong Learning offerings for the current semester.

“The two big spiritualist centers in the country were Battle Creek and Buffalo, N.Y.,” Owens says. “Spiritualism peaked between 1840 and 1920. There were eight million practicing Spiritualists in the United States and Europe and it’s still a church today called the Spiritualist Church.”

Owens says, “These spirit mediums like (Battle Creek’s) Mrs. Walling were sought after because there were so many lives lost in the Civil War and in World War I and their loved ones were desperate to find ways to communicate with them from beyond the grave.”

In March 1877 she says, about 50 Spirit mediums from throughout the United States gathered in Battle Creek’s Stewart Hall to celebrate the 29th anniversary of Modern Spiritualism.

“In the summer of 1881 spiritualists thronged to Goguac Lake for the Annual Camp Meeting of their State Association,” Owens says. “Battle Creek was appealing because we were right in the middle between Chicago and Detroit and there were all of these religious groups growing up around here.”

Those groups were influenced by the teachings of various religions and movements including the Mormons, Millerites, Quakers, Abolitionists, Phrenologists, and the Swedenborgian Church. Another religious movement supported vegetarians.

Owens says Battle Creek provided fertile ground for spiritualism and different religious views because “we were just really wide open to ideas. The thinking at the time was that if you didn’t agree with certain religious teachings, you started your own. At one point we were the only town in the United States that had a Swedenborgian and a Spiritualist church.”

Mary Green, Director of KCC’s Lifelong Learning, says the classes in Spiritualism have “been a part of our offerings for years. They are like that little gem that nobody knows about.”

In addition to the Spiritualism classes, Owens will also teach a class on Oct. 27 titled “Ghosts and the Supernatural.”

Green says evaluation forms filled out by Lifelong Learning students and research into what types of subjects are being offered in larger markets are used to determine what classes KCC could offer.

“We take a look at a few of those and get ideas for classes and decide if it’s something we want to offer,” Green says. “We use a network of connections to find instructors and people in the community. You don’t need a degree, you just have to have a passion for the subject matter and want to teach.”

Owens, who retired from teaching in 2009, has been a Lifelong Learning instructor for several years. Her previous classes have included a focus on insane asylums and weather fads from the 1890s to today.

“The more gory they are, the more people I get,” she says.

KCC’s Lifelong Learning component was established in the early 1970s as a non-credit option with a mission to connect the community with the college in a way other than attending traditional for-credit classes, Green says.

“This is a way to be engaged and socialize and be part of the college in a different way for people who may not be interested in taking traditional classes in college,” she says.

Spiritualism’s roots in Battle Creek

The Spiritualist movement began in the 19th century in the bedroom of two young girls living in a farmhouse in Hydesville, N.Y. On a late March day in 1848, Margaretta “Maggie” Fox, 14, and Kate, her 11-year-old sister, waylaid a neighbor, eager to share an odd and frightening phenomenon, according to an article in Smithsonian Magazine. “Every night around bedtime, they said, they heard a series of raps on the walls and furniture—raps that seemed to manifest with a peculiar, otherworldly intelligence.”

The family abandoned what appeared to be a haunted house and the sisters eventually were sent to Rochester, N.Y., to live with an older sister. They would go on to practice their ability to communicate with the spirits in both small and large gatherings of the curious. Coincidentally, Rochester was a hotbed for reform and religious activity; the same vicinity, the Finger Lakes region of New York State, gave birth to both Mormonism and Millerism, the precursor to Seventh Day Adventism, the article says.

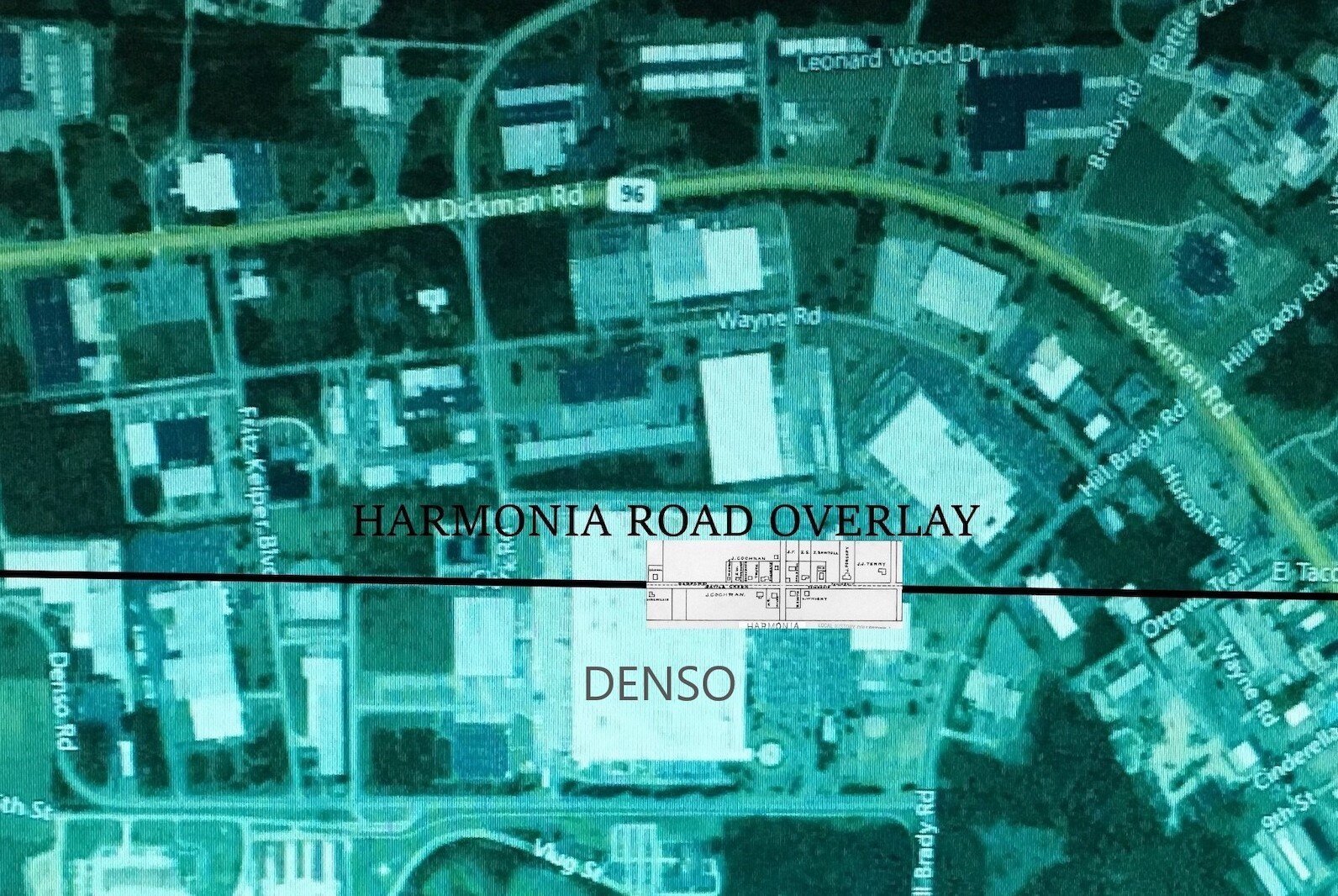

In addition to the Fox sisters, Owens says the other big name in Spiritualism at that time was Dr. James Peebles who combined Swedenborgianism and Spiritualism. Together, with a group of Quaker pioneers in Battle Creek who had embraced spiritualism, Peebles formed the village of Harmonia, a Utopian community whose most famous resident was Sojourner Truth. Harmonia, now a ghost village, was located on land occupied in part by the Denso facility in Fort Custer Industrial Park, says Kurt Thornton, a local historian.

While the advent of a community like Harmonia and different religions were finding their place in Battle Creek, new ideas were taking root that complemented the non-traditional ways of thinking such as a focus on the vegetarianism movement that was being put forth by Ellen White, founder of the Seventh Day Adventist Church, and Dr. John Harvey Kellogg, founder of the Battle Creek Sanitarium.

“They were so far ahead of their time with their beliefs about health, no smoking, no drinking, and vegetarianism,” Owens says of Kellogg and White. “Vegetarianism came from Rev. Dr. Sylvester Graham who invented crackers that did not contain refined sugar, an ingredient he was adamantly against. He spent time in Battle Creek as well.

Not without its share of skeptics

The legitimate and well-intentioned efforts that fostered different religions and ways of thinking for a time in Battle Creek overshadowed attempts by those like Mrs. William Walling who were seeking to take advantage of individuals looking to connect with the spirits of their deceased loved ones.

Owens says she was not able to find a first name for Mrs. Walling, which is not unusual because during the late 1880s women’s identities continued to be tied to that of their husbands.

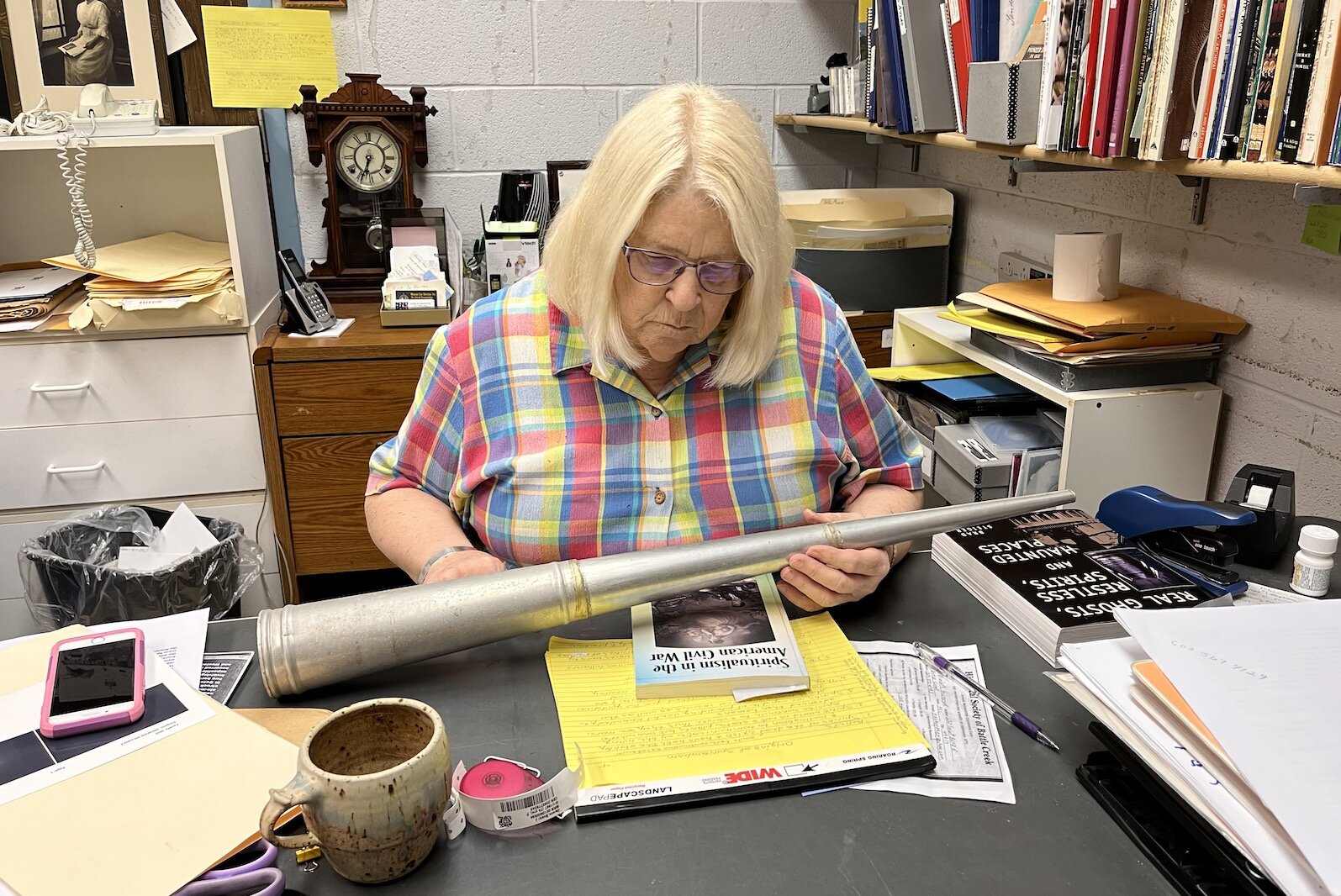

A written account called “The Walling Expose – December 1883” put together by Owens, tells of a particular séance that exposed her fraudulent tactics.

“Mrs. William Walling, when she started doing her seances in Battle Creek, was doing them out of her home. People had to pay 50 cents and they were in a darkened room and sat around a table where everyone was holding hands and she could summon spirits. She had a spirit guide like all mediums did,” Owens says.

The Walling’s home was an octagon-shaped house at 41 North Avenue. (That address has since been changed to 159 North Avenue.)

Owens says, “Everyone in Battle Creek was flocking to her séances to see what spirits would materialize. Spirits of famous local figures were seen, including Sojourner Truth, who had died a few weeks before one séance.”

However, Walling would be exposed as a fraud by a group of prominent male citizens who attended a séance to see if the “manifestations were genuine,” Owens says in her written account.

During the course of the séance, one of the men, Dr. Wattles, insisted on shaking hands with a “spirit” through the partially closed door of the cabinet. Soon Mrs. Walling was exposed.

“She was in the cabinet and at one point some spirits were supposed to materialize and someone at the séance wanted to shake hands and a hand comes out and when Wattles shakes her hand and the ‘spirit’ pulls back, he pulls someone out and it was Mrs. Walling.”

Mr. Walling would be arrested and charged with violating a city ordinance relating to licensing exhibitions. He was arrested instead of his wife because he owned the home where the activity happened. He was ordered to court and paid a fine of $39.60.

The city’s two local newspapers – the Journal and the Moon – began their own investigations and discovered that Mrs. Walling had been “denounced as a trickster and a fraud” in Chicago and Terre Haute, Ind. before she moved to Battle Creek with Mr. Walling to ply her trade.

Owens says the couple moved outside of the city limits to avoid further legal issues and she continued to hold seances. Despite the negative publicity, Walling continued to have quite a following.

While a spiritualist movement continues throughout the world and maintains its share of believers and detractors, Owens says she will continue to present information that will leave her audiences to draw their own conclusions.

“My role as a historian is to share what I have uncovered about Battle Creek’s rich past and share those anecdotes and stories with others,” she says. “There is so much that residents of Battle Creek don’t know about their city and past events that helped shape it into the city we see today.”