A tale of two cities: South Bend has been where Kalamazoo is now and the future is promising

'Quieting' downtown streets is a noisy process. Change can be unsettling. Ask any Kalamazoo resident. But South Bend, Ind. has completed the transition of urban one ways to two ways. The results are encouraging: downtown reinvestment, beautification projects, and increased community pride.

Editor’s note: This story is part of Southwest Michigan’s Second Wave’s On the Ground Kalamazoo series.

KALAMAZOO, MI — We’ve heard a lot of this before from the Kalamazoo’s city planners and traffic engineers.

Wide, multi-lane, high-speed, one-way roads through downtown have to be changed to two-way city streets, with traffic-calming elements. The city’s downtown needs a major change, not just for the safety and benefit of pedestrians and bicyclists, but to improve business and make downtown a place people want to live, work, and play.

Eight years ago, city planners in South Bend, Indiana, were saying the same things.

Those reasons for making a big change to South Bend’s downtown streets are all in the past now — because most of the change has already happened, beginning over seven years ago.

Two midwest cities of similar sizes responded to similar circumstances and visions.

In 2024, South Bend has completed much of the street work that Kalamazoo is just beginning. One could say that South Bend exists as a prototype of Kalamazoo’s near future.

Results may vary, but South Bend might have answers to a recurring Kalamazoo question: What will downtown be like once Michigan Avenue and Kalamazoo Avenue become two-way and after most of the traffic calming and pedestrian/bike-friendly infrastructure is done?

And there’s that additional question, often repeated on social media and at city meetings: Why all the changes, anyway?

Tim Corcoran, Director of Planning and Community Resources for the City of South Bend responds to that question for his city, “Part of our thinking is that downtown is for everybody, and it isn’t just merely a conduit to move cars through the city as fast as possible. And we want to support businesses, we want to support anyone who wants to come and visit our downtown. I think we’re a little less concerned about people who just want to go through downtown.”

A tale of two cities’ one-way streets

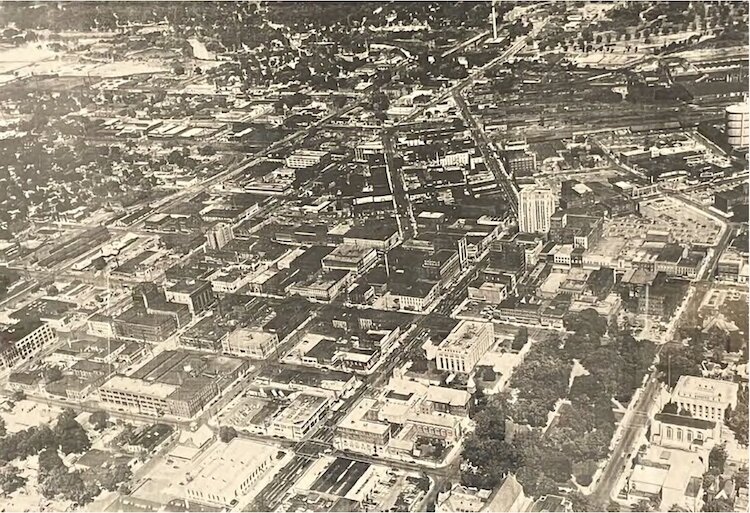

South Bend (population 103,501) and Kalamazoo (73,598) are comparable Midwestern cities. South Bend was established just after the Civil War; Kalamazoo, as we know, was a village that grew around Titus Bronson’s cabin, but wasn’t officially a city until 1883. Both are centers of higher learning, with the University of Notre Dame there, Western Michigan University and Kalamazoo College here.

Both had what city planners like to call “old bones,” infrastructure and buildings that grew with the cities. Both went through the urban renewal era in the mid-20th century which cleared a lot of the old buildings and housing for parking lots and saw wide roads become throughways dividing their downtowns.

Corcoran has been to Kalamazoo often — he enjoys seeing concerts at Bell’s Eccentric Cafe, he says.

In Kalamazoo, “I see a city that’s in a lot better shape than ours,” he says. “We tore down a lot of great buildings — urban renewal, we really embraced that. That did nothing at the end of the day, did nothing for our community. If anything, it really damaged it.

“I could see some of the mistakes (in Kalamazoo) that we had made, but it seems like you didn’t really double down on them like we did. So your town to me felt a lot more intact than South Bend did. Lots of cute buildings and some cool things to do, so I applaud you for that.”

When Corcoran arrived at his position in the spring of 2016, South Bend was at the beginning of its Smart Streets construction. He wasn’t involved in the planning, but he was there for “the implementation and the follow-up.”

Mayor Pete’s Smart Streets initiative brought in bike paths, planted trees, and widened and beautified sidewalks for South Bend’s downtown. Its centerpiece was the conversion of two major one-way streets to two-way, Main Street and MLK Boulevard (then known as St. Joseph Street).

The two streets were four lanes each, with parking. Sound familiar? The streets became one lane in both directions, with a center turn lane. Construction began that spring, and both streets were finished in November 2016.

“Yeah, it was very fast,” Corcoran says. “They wanted to make sure that the impact was minimized…. I think that rushing it can lead to, you know – some things that could have been potentially done better.”

Mayor Pete Buttigieg left to become U.S. Secretary of Transportation in 2021, but the city has continued to evolve with street changes, traffic calming, and beautification projects. The current big project is the removal of a cloverleaf interchange that was built to transport workers at the Studebaker plant. The plant closed in 1963, and “the infrastructure became unnecessary as soon as it was built,” according to an article in the South Bend Tribune in 2022.

South Bend’s downtown transformation, like Kalamazoo’s, is aligned with the Complete Streets philosophy, Corcoran says, which calls for streets that serve all users, not just people in cars.

“One of the most important things that we think about in all of our streetscape projects, in our neighborhood plans, is that great places begin with great streets. They go hand-in-hand. You can’t have a really great place without a great public domain in which the streets are a major part of that,” Corcoran says.

So? How did it all turn out?

After the 2016 conversion, “We instantly saw a lot more interest in reinvesting in properties downtown. We had something close to $100 million worth of new reinvestment into buildings that have been vacant or underutilized in downtown,” Corcoran says.

According to a 2019 South Bend Tribune story, some developers were planning to invest in the city anyway, street conversion or not. But the changes were a “key secondary factor,” at least with J.J. Patel, a developer behind a new $14 million hotel.

“Overall, with the two-way streets and the apartment people, it’s a livelier downtown,” Patel told the South Bend Tribune back then. “Everything kind of came together and it’s cleaned up the whole area. You’ve got a different image when you go down there now, compared to five years ago.”

Between late 2016 and 2019, there’d been a lot of growth in a short time, the paper noted — new hotels, apartments, and restaurants.

“There was a lot more interest in downtown, and I think that has continued,” Corcoran says. “We have currently about a billion dollars worth of new investment, both public and private, that are happening in our downtown area, including upgrades to our baseball stadium and our Performing Arts Center, but also new apartments and mixed-use projects,” Corcoran says.

“The way the major streets were before, again, were high-speed, they were ugly, the sidewalks were narrow, there’s very little vegetation. All of these things really tell you to stay away. They’re not telling you to come here or they’re not encouraging folks to want to be in a place,” he says.

There were people in South Bend, as there are now in Kalamazoo, who feared that the changes would kill off their downtown, ensnarl it with traffic backups, and keep visitors from the area. Did any of that happen?

“No!” Corcoran exclaims, laughing. “I think it added maybe three to five minutes (to trips) through the project area, which was a very large project area. It spanned very far to the south of downtown.”

“Personally, I had some friends who originally were very skeptical of the project…. they said something like, ‘Now why would you do this?'”

His friends were doubtful, “but then I started to see them at downtown events more often, and so they, I think, realized at the end of the day that it was a positive improvement for our community.”

Corcoran says there’s been no organized movement to revert to the way things were, and there’s only motivation for South Bend to continue the work. It’s all very economically sustainable for the city, he says, helping to grow tax revenues. He compares a popular downtown bar with a nearby shopping mall — the bar generates more tax revenues per acre than the entire mall.

“I don’t think we’re gonna worry too much about people who don’t spend any time downtown and just want to go through. Those folks aren’t contributing to the health, and the life, and the vibrancy of our downtown. Maybe over time, we can win them over and they can begin to see the positive effects that a project like this has had for us. But it does take time.”

Kalamazoo’s past, present, and future

Rebekah Kik, Kalamazoo’s Assistant City Manager, pointed us toward South Bend as an example of what Kalamazoo is hoping to do.

We asked her the question on a lot of people’s minds: Why is this all happening now?

“Honestly, if we were going to have an amazing, economically-friendly, welcoming-to-all place with what we have (now), gosh, we’d have a totally different place, right?” Kik says.

“If our goals are to have this economically diverse and growing city, we can’t get that by staying where we are.”

Changing downtown’s streets hasn’t been a sudden effort that came out of nowhere, she points out.

Kalamazoo and Michigan Avenue were converted to one-way in 1964. “By 1968 things really started to go awry and they were saying, wait, maybe we didn’t make the right choice. And that was the first study to change the traffic back to two-way,” Kik says.

The city did another study in 1977, and still more studies in the ’90s. The city gave control of the streets to MDOT, “because the city just didn’t have the money to take care of those streets,” she says. “Then we really tied our hands behind our back on making any other future decisions from the ’80s forward,” because of MDOT control.

In 2015, the city started talking to MDOT about getting the streets back, “so that we could consider a different vision for our downtown, that’s when the tide changed. That’s when we got to say, wow, we could really envision something different happening, and got the momentum to do so.”

Public studies including the Kalamazoo Area Transportation Study (KATS) and Imagine Kalamazoo 2025 were developed through community engagement and further solidified plans for future changes.

In 2023 the University of Notre Dame School of Architecture, along with participants from the City of Kalamazoo, released a finely detailed 81-page study of downtown. It covers everything from street changes to zoning changes to the species of trees that should be planted along downtown streets.

All these studies and plans aren’t pushing strange, new ideas, Kik points out. Especially the conversion of one-way to two-way streets — “They’ve been happening for decades in other towns. In fact, we’re definitely the late adopters.”

She says the city is working with consultants who’ve worked on such conversions that were completed or are happening in New Albany, Indiana; Oklahoma City, Oklahoma.; Lowell, Massachusetts; Davenport, Iowa; Boise, Idaho; Cedar Rapids, Iowa, Kik says. “These are towns that are relative in size to ours,” she says, “not San Francisco and New York, right?

“Nationally, there are so many other downtowns that understand, and have taken up the same mantle and said, we also aren’t seeing the success we need from large parking lots and fast one-way streets.”

Kik says that the one-way streets and high-speed traffic cut off neighborhoods from downtown, affecting housing and other developments, and business in general. “And we put that out to the public, and especially when you talk to property owners, business owners, and residents, they say, make the change.”

But some vocal critics don’t want change, as one can see from social media comments.

“This is totally my speculation… The people who are really upset at us are the people who just drive through downtown, and they’re just headed to Gull Road or the opposite direction. They’re just headed up West Main. They’re headed to Portage. They’re not stopping in Kalamazoo. We’re just this convenient cut-through for them. And they’re upset that we’re jamming them up for an extra two-and-a-half or three minutes on their commute to somewhere else,” she says.

“We have to look at the Complete Streets philosophy. Once we get the streets right, then the developers go, okay, I’m in. And that’s how South Bend changed, they did the streets first because they knew, again, the development wasn’t coming.”

The motivation to do this now is also coming from the fact that the money is there — however, funding is in what Kik calls a “lasagna” form. That’s “when we get many funding sources that you stack up together to make a project move forward.

“The majority of the funds are from the federal infrastructure bill,” she says. Federal funding includes a RAISE (Rebuilding American Infrastructure with Sustainability and Equity) grant and a Reconnecting America grant.

MDOT dollars and the city’s capital improvement fund will also go into the lasagna. Grants from the Irving S. Gilmore Foundation, the Kalamazoo Foundation for Excellence, and others are being requested to go into beautification and placemaking efforts, she says.

The need for outside funding calls to mind Kik’s statement that the city handed off its two major streets to MDOT back in the 20th century because the local tax base couldn’t pay for their upkeep.

Is the motivation to do this all economic? Is it all about the money? Could the changes lead to a tax base that keeps the city sustainable?

“That would be a great outcome, you know? I think that probably hits third or fourth on the list,” Kik says.

“I think the first outcome that we want from this is certainly a safer, more walkable, livable environment for the people visiting from our neighborhoods to the downtown, from the colleges to our downtown.”

If downtown becomes “a place they want to stay,” then “investment follows, people’s businesses that are already here grow because now they’re more accessible.”

Economic growth and increased traffic safety seen already

Kik adds that growth is happening now.

She points out that the warm-up to the street conversions, the Michigan Ave. pilot that included bike lanes and other traffic-calming changes, has not driven down visits to downtown.

In fact, visits are up. Discover Kalamazoo has “this amazing data about all the people that are visiting in the downtown. I’ve got my downtown businesses that are telling me that they’re doing better than they have since COVID, that they’re thriving and they’re doing really well,” Kik says.

Dana Wagner, Discover Kalamazoo’s Director of Marketing and Communication, says, “Everything shows that visitation has increased when you compare 2023 to 2022.”

In all of 2022, there were 981.7K visitors to downtown. In 2023, there were 1.1 million visitors, Discover Kalamazoo shows. Visits during the later months, comparing Michigan Avenue before and after the new bike lanes, were up also.

During the holiday season, there were 334.1K visitors in 2022, and 369.3K visitors in 2023. The downtown holiday parade saw attendance doubled, 20.3K in 2022, and 45.7K in 2023. The Chili Cook-Off in January brought in 26.4K visitors in 2023, and 29.2K in 2024.

Most impressive, Kik points out that, although “our traffic numbers are showing that we’re up like one or two thousand cars per day,” traffic collisions involving injury are down.

We checked with the City’s Traffic Engineer, Dennis Randolph, and he confirmed with the Michigan State Police. For the downtown Kalamazoo area, Michigan State Police crash data for the periods of August 1, 2022, to February 21, 2023, and August 1, 2023, to February 21, 2023, show a -2.8% reduction in personal injury crashes, a -1.7% reduction in property damage only crashes, and a -1.9% reduction in the total reported crashes.

“While a relatively short period, the reductions in crashes reflect a positive trend,” Randolph says. “The decrease in crashes can be attributed in part to speed reduction, which has been about four to five miles per hour reduction in the average speed.”

Randolph emphasizes that this data is from “a relatively short period of time.” He says, “Overall, for the downtown area, despite a lot of construction and detours the results so far are positive. Also, this has been a big learning experience for many drivers, and we expect even better results as drivers become more accustomed to the new lane configurations.”

Kik says, “There’s real evidence that’s showing there are more people downtown, less accidents — we’re doing something right.”

So, when it’s all done, will Kalamazoo see the success that South Bend brags about, with hundreds of millions of investment dollars coming in, along with walkable, inviting, streets?

Kik thinks more along the lines of, “What’s the city gonna look like for my 11-year-old, who will be, you know, 21 by the time these projects are wrapped up and looking beautiful? I hope to have a vibrant and thriving downtown, where lots of people can come into our downtown from multiple modes…. (with) our neighborhoods more connected to our downtown.”

The big change is underway right now, starting with Michikal Street. The two-way Kalamazoo Avenue conversion follows, then Michigan Avenue.