This article, originally published in New/Nuevo Opinion, is part of A Way Through: Strategies for Youth Mental Health, a solutions-focused reporting series of Southwest Michigan Journalism Collaborative. The collaborative, a group of 12 regional organizations dedicated to strengthening local journalism and reporting on successful responses to social problems, launched its Mental Wellness Project in 2022 to cover mental health issues in southwest Michigan. Para leer este articulo en español dale click aqui.

It was a tragedy that roiled Battle Creek Central High School.

Feb. 24 was a frigid Friday night. So as 17-year-old Jack Snyder was driving home from his girlfriend’s birthday party, he offered a ride to two younger boys he didn’t know.

It was a Good Samaritan act that appeared to cost Snyder his life. The boys, ages 13 and 14, allegedly initiated a carjacking and shot and killed Snyder, a Battle Creek Central honor student and varsity soccer player.

As grief washed over the school community, students’ need for support didn’t fall solely on the school staff. Another avenue was Grace Health, a public health agency that has a clinic at the high school.

Through Grace’s team of providers and referrals to other local mental-health services, students were able to get the help they needed to process the shooting death, says Ashley Roberts, Grace Health manager of clinical services.

Grace Health, which has operated the Battle Creek Central clinic since 2018, offers a range of services, including sports physicals, urgent care, immunizations, and behavioral/mental health care. It’s open year-round and is available to the public, for patients ages 5 to 21.

The clinic accepts Medicaid and most insurance plans, and has a sliding fee scale based on income and family size.

In 2022, the clinic served 600 patients in 1,300 visits. About half the patients are Battle Creek Central students and the other half are other youths in the community,

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, most visits were related to physical care. But since 2020, the demand for mental health services has been growing, Roberts says.

“We are on track for mental health services to be the leading service line, probably, in our student health centers,” she says.

In Calhoun County, Grace Health operates full-service clinics in Battle Creek Central and Lakeview high schools and Northwestern and Springfield middle schools. Grace Health also has behavioral health clinics in Harper Creek and Kellogg Prep high schools; North Pennfield, Verona and Purdy elementaries, for Homer Community Schools.

According to Roberts, Grace Health’s behavioral health consultants provide onsite counseling services to students in the above-named schools. Those social workers have a high level of expertise and experience in conditions such as stress, anxiety, grief, and depression. If a student needs more specialized behavioral or mental health care, the Grace Health social worker will work with the student and their family to get connected to additional services.

School-based clinics are filling a critical void in Michigan’s health-care system, particularly in the face of rising demand for mental health services, says a 2022 report by the Citizens Research Council of Michigan, a nonprofit think tank.

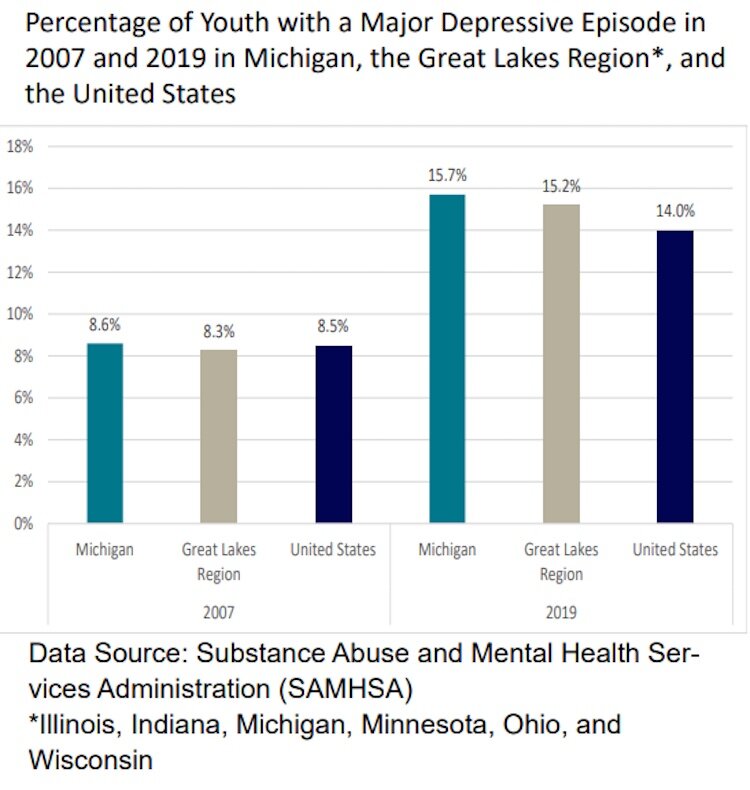

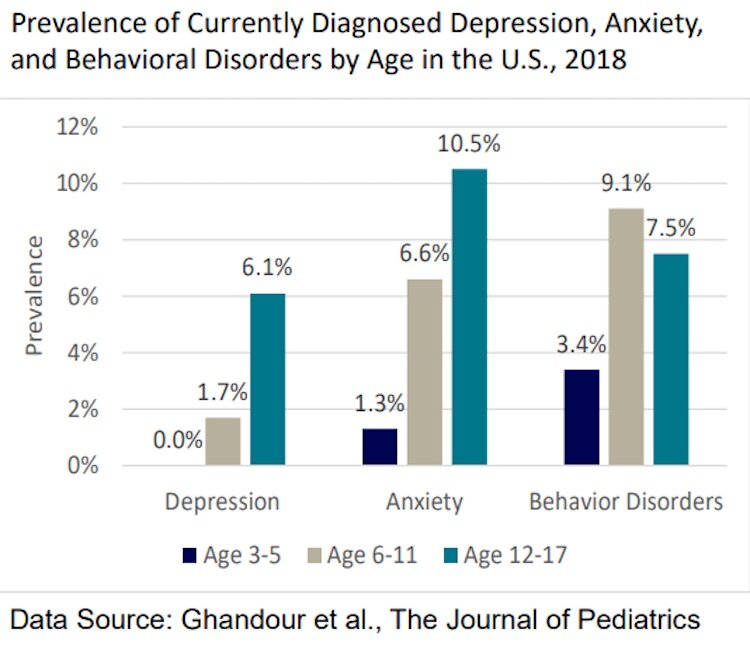

The CRC report points to the skyrocketing rates of behavioral health issues among Michigan youth, as well as issues around access to treatment.

In February 2023, the federal Centers for Disease Control reported a “dramatic” rise in experiences of violence, poor mental health, and suicide risk in teens, especially in girls.

Indeed, 42% of high school students felt so sad or hopeful almost every day for at least two weeks in a row that they stopped their usual activities, the CDC says.

And suicide is now the second-leading cause of death for adolescents and young adults.

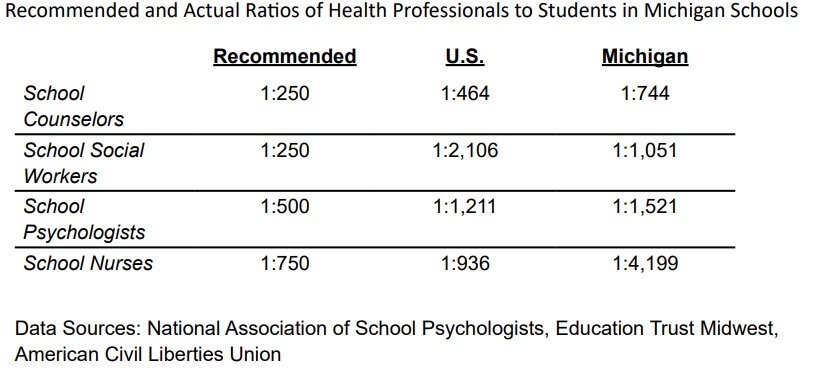

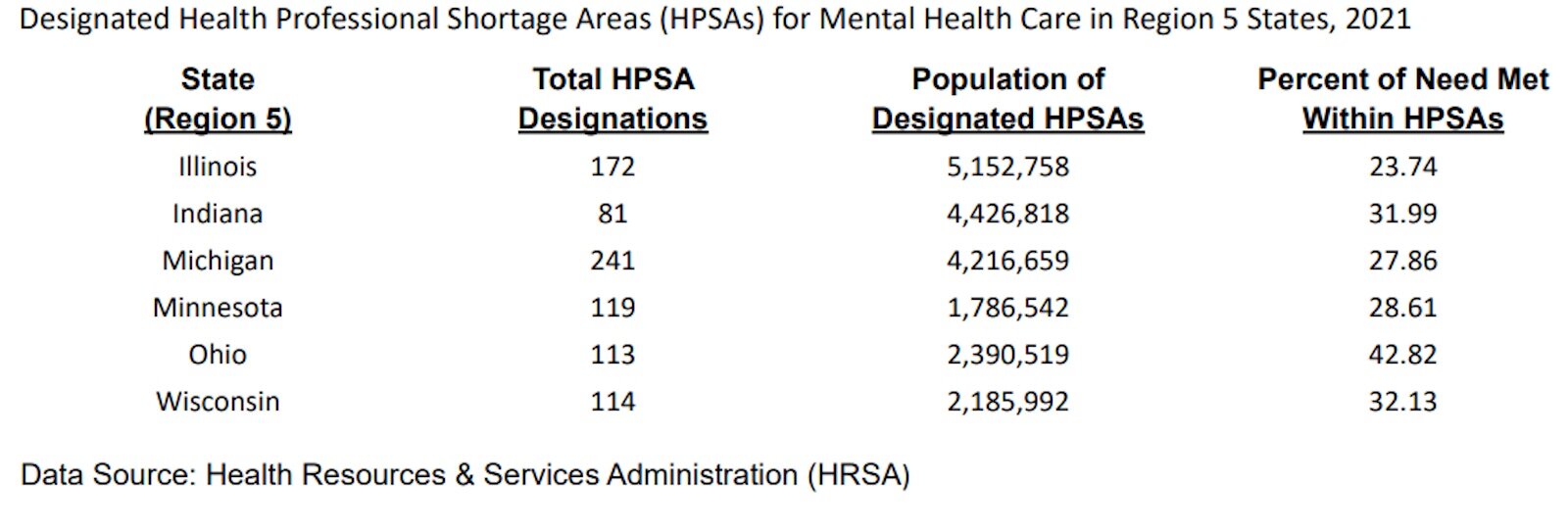

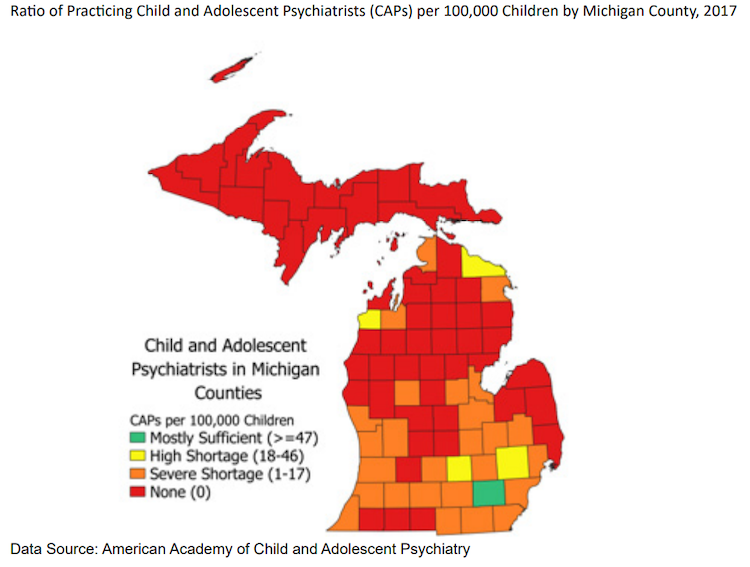

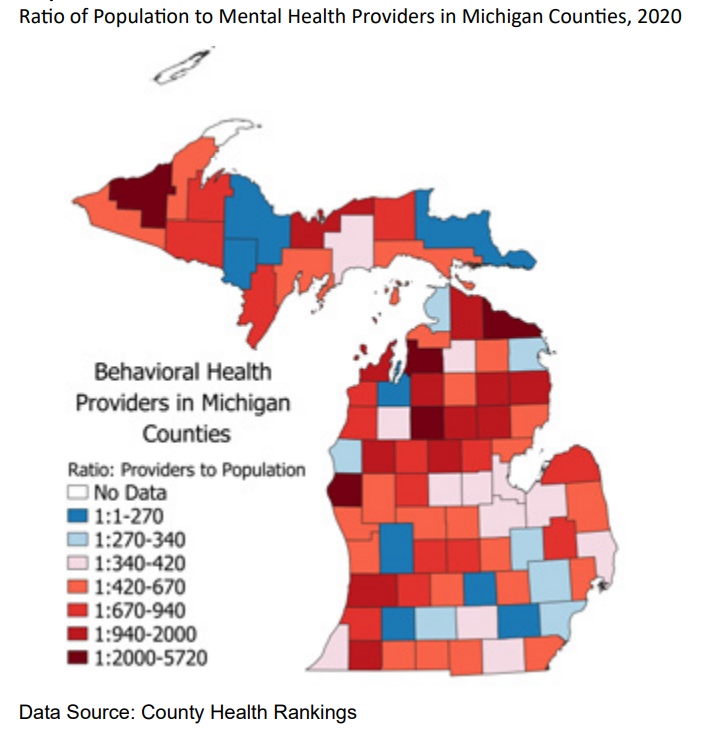

At the same time, there’s a dire shortage of mental-health professionals for children – both inside and outside of school, the CRC report says.

School-based clinics help address these issues on multiple levels by offering easy access to free or low-cost mental-health services, says Craig Thiel, research director of the Citizens Research Council.

“Because kids spend a considerable amount of their day and their week in school, it’s logical to situate those centers in schools,” he says. “Doing so, it breaks down the access challenges to mental health services that occur outside of school like transportation.

“These are largely free health centers in the schools available to anybody. You don’t need to have insurance,” Thiel says. “These aren’t costing the kids anything to seek counseling.”

School-based clinics also help break down the stigma around mental-health care and offer an “ideal milieu to deliver information around mental health and teach social and emotional skills that foster resilience,” the CRC report says.

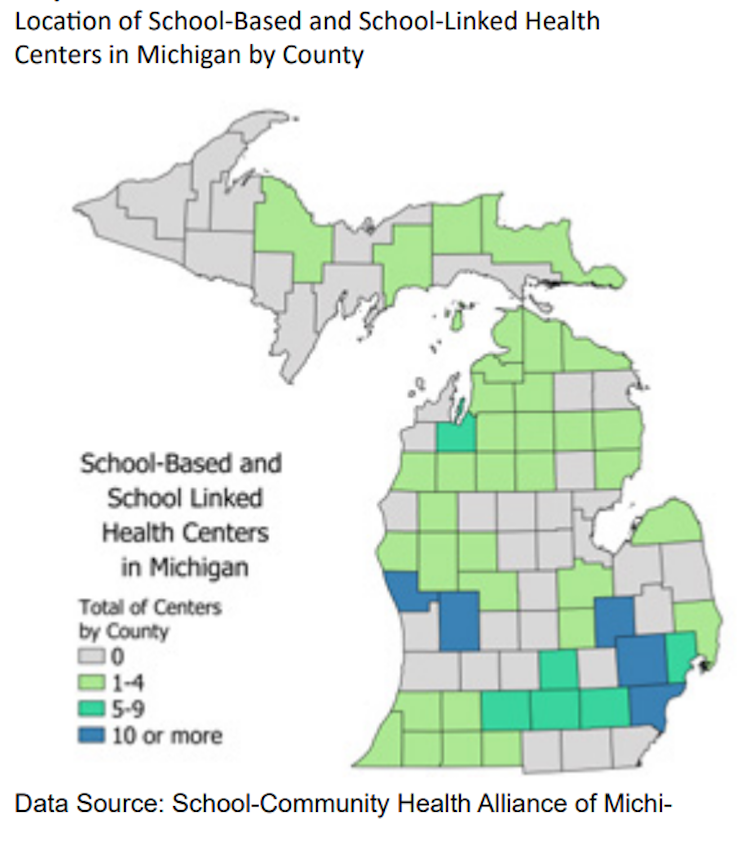

About 200 Michigan public schools have school-based or school-linked clinics, the CRC report says.

Roberts says having behavioral health counselors present in schools allows faculty to focus on their primary job of educating students.

“It takes pressure off from the school staff that are already turfed or challenged to be able to just provide education to our kiddos in the community,” Roberts says. “It gives another set of eyes, another opportunity to ask different questions, to be a positive adult in the building.”

Thiel says one of the largest obstacles that school-based health clinics face is a lack of funding.

“It’s not that anyone has been explicitly against these programs,” he says. “It’s been more the case that academics have been given more of a priority.”

The Michigan Department of Health and Human Services recently announced $2.4 million in planning grants that will go to 26 child and adolescent health centers across Michigan. The pilot school districts include Otsego Public Schools, Concord Community School District, and Kentwood Public Schools, among others.

Despite challenges, Roberts describes Grace Health as a success just by its presence. Grace tailors its efforts toward what is going on in the Battle Creek community at the time — like the February shooting of Jack Snyder, the Battle Creek Central student.

Especially in schools with younger student populations, like Verona Elementary, Grace Health empowers students to understand their health needs and how to care for them, Roberts says.

“Verona is not a traditional elementary,” Roberts says. “It’s third grade through fifth grade, so I feel like that is such an instrumental time of life to empower the kids to understand the importance of maintaining good physical health, but also mental health and what it looks like and how it’s important to recognize it quickly and the resources that are available to help support them.”

The CRC argues that Michigan needs to invest more in school-based health clinics, saying they “provide an ideal mechanism for both treatment and prevention at an early juncture in people’s lives.”

“Efforts should be made to expand this model,” the report says.