Planting seeds: National movement with local ties works to restore Native cultural food traditions

Once forced to abandon their way of life, the Nottawaseppi Huron Band of the Potawatomi are among those Native Americans nationwide who are teaching tribe members traditional ways of fishing, foraging, planting, and hunting.

Editor’s note: This story is part of Southwest Michigan Second Wave’s On the Ground Calhoun County series.

The growing appetite to restore food systems that were central to their health and culture for centuries has created a national movement among Native American tribes and the Nottawaseppi Huron Band of the Potawatomi in Athens Township is part of it.

These food systems centered around fishing, foraging, and hunting were all but abandoned — not by choice — when tribes were stripped of their land and younger generations were forced into government-run boarding schools where they were banned from using their own language and names or practicing their religion and culture. As a result of this government-sanctioned action to strip tribes of their culture, many young people did not have the knowledge required to continue or maintain the food systems that flourished under their ancestors.

The Nottawaseppi Huron Band of the Potawatomi (NHBP) Tribal Historian Preservation Officer Doug Taylor says people with this knowledge among the Tribe now are teaching these traditions to any member who wants to learn them. While not everyone attends these teaching sessions, he says it’s an important part of an overall plan to increase cultural knowledge and improve the health of Tribal members for generations to come.

“It gets us back to our old ways and our traditional ways,” Taylor says. “It’s important to embrace our history and bring it back. We can’t go back in time, but by having that tradition brought back, we can remember it and pass it on. We have members who will keep the history alive by actually practicing these traditions.”

Some of these members are homesteaders who get connected to those who want to learn the traditional ways of hunting, fishing, and growing the plants that are native to their culture.

“We teach indigenous life through current means,” says Fred Jacko, Culture and Historic Preservation Office Manager with the NHBP. “We use a lot of current technology to begin to educate our community on the different avenues available to them. We start individually and we champion cultural practices and language.”

For the most part, Jacko says members are excited about having the ability to learn the traditional ways of their people.

These local efforts are supported by the Native American Food Sovereignty Alliance, seeded in 2005 with funding through an Oxfam America grant that brought together grassroots Native food activists to make a greater impact on Native American food systems. During these meetings, participants from 13 tribes came together to share their knowledge and skills in agriculture, seed saving, and foods. These activities resulted in the first attempted seed sovereignty declaration and a completed Food Sovereignty Declaration with a Call to Action. (see more here)

Seed sovereignty is the farmer’s right to breed and exchange diverse open-sourced seeds, those that can be saved and which are not patented, genetically modified, owned, or controlled by emerging seed giants, and reclaims seeds and biodiversity as part of the common and public good, according to activist and Global Seed Ambassador, Vandana Shiva Navdanya.

As the NAFSA says, “Seeds are a vibrant and vital foundation for food sovereignty, and are the basis for a sustainable, healthy agriculture. We understand that seeds are our precious collective inheritance and it is our responsibility to care for the seeds as part of our responsibility to feed and nourish ourselves and future generations. As a national network, we leverage resources and cultivate solidarity and communication within the matrix of regional grass-roots tribal seed sovereignty projects.”

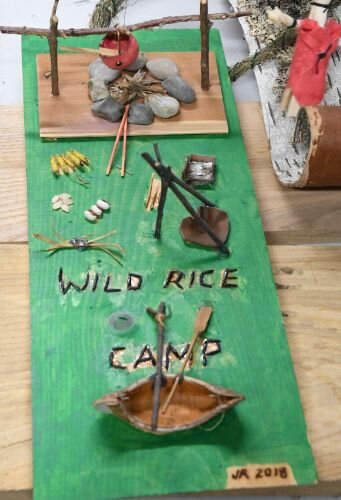

The seeds that produce wild rice are among the most coveted, says John Rodwan, Environmental Director with the NHBP.

This type of rice which was at one time central to the Native American diet used to grow in abundance in riverbeds. But the proliferation of invasive species slowly destroyed the natural ecosystems that allowed the rice to grow in rivers, Rodwan says.

“Our sub-watershed, which is the Nottawa, has some very good occurrences of wild rice and the Kalamazoo watershed does as well, but the St. Joseph River is a little more prolific,” Rodwan says. “It’s really the two watersheds. We do harvest river rice, but we don’t have enough to feed the community. The rice we have now is for ceremonial use and seed stock.

“We use the seed stock to replenish and supply, but we’ve got to beat back invasive species. There are just pockets of wild rice, where it used to be abundant, it’s now just spotty. We try to re-establish beds, it’s an annual so it has to re-seed each year and some seed actually lies dormant for years. It’s very difficult to restore wild rice.”

Its rarity is such that the Tribe can only collect 10 percent of what is grown annually and must have a permit issued by the state’s Department of Natural Resources to harvest the wild rice.

A federally-funded grant provided resources the Tribe has used for more than 10 years in its work to re-propagate riverbeds with wild rice. This work led to them becoming the leading authorities in the region, Taylor says. Three years ago they were approached by researchers with the University of Michigan who were interested in the techniques being used.

“They asked for our help to show them how to grow wild rice,” Taylor says. “Wild rice is a different type of a plant. You just don’t throw it in the water and say ‘See you in a little while.’ It takes years of experience and cultivating. Even if you do it all right, it may not want to grow. We seem to have mastered the art of growing wild rice.”

Rodwan says this mastery falls under Traditional Ecological Knowledge.

“A lot of the federal programs are looking for climate adaptation farming and they’re looking to Tribes who have been a sustainable people through adaptation,” he says.

A costly lapse in sustainability

Tribes have been in survival mode for many, many years and now have the ability to move forward in their history, Jacko says.

“Learning to cultivate indigenous foods is a natural progression for us similar to the language and the history. You can’t have one without the other,” he says.

Native Americans were made all too aware of this when the Federal government began an assimilation process in 1885. Since there was no further Western territory to push them toward, the government decided to remove Native Americans by assimilating them. Commissioner of Indian Affairs Hiram Price explained the logic: “It is cheaper to give them education than to fight them.”

As part of this process, Native American children were given new Anglo-American names, clothes, and haircuts, and told they must abandon their way of life because it was inferior to white people’s.

“The government tried to take away our culture. They put our kids in boarding schools and forbid them from wearing their hair long. They tried to decimate our culture and turn the Indian into a white person,” Taylor says.

After centuries of growing food, and hunting and fishing traditions that followed the seasons, Native Americans for the most part were forced to abandon a diet that maintained their health, although there were some who went underground and quietly continued those traditions that they grew up with.

“Because our traditional foods changed over the seasons, our food habits and menus changed as the seasons changed,” Taylor says. “It was kind of unique how that society worked overall. It was tied into that lifestyle of taking and growing only what you need. Back then we didn’t have that many associations with another culture. We were isolated from other diseases.”

As processed foods were introduced into their diets, incidences of cancer, diabetes, heart disease, and strokes began to escalate. As a child growing up on the NHBP’s Pine Creek Reservation, Taylor says bacon grease was used like olive oil and the fresh foods his ancestors grew up on were virtually non-existent.

Jacko says, “The U.S. government-led programs to get foodstuffs to native communities included white flour and ultra-processed foods and we weren’t ready for that high sugar content. The foods we were given were inappropriate for anyone to consume. You’re not exerting energy to get that food and it’s chockful of calories. We weren’t putting in the exertion and we were eating food that’s terrible for our bodies.”

“If we were left alone in our own traditional ways of eating food, we wouldn’t have had the heart disease and strokes and cancers associated with other society, Taylor says.

However, those traditional ways require a significant investment of time to grow, hunt, fish, and forage for that food. In the society that Native Americans find themselves a part of, Jacko says the focus is on making money which leaves little time to practice the traditional ways of gathering food.

“We’re part of an overall culture in the United States,” Taylor says. “When we first started out it was really on the Tribes and the families who worked together, but as times changed we went from farming to general labor work and people started migrating away from the Tribe and their families and moving to Battle Creek, Kalamazoo, or Grand Rapids because they wanted to make a living and have the ability to buy a car, have a nice house and send their kids to college.”

This migration created an even greater divide between the traditional way of life and what had to be done to live in a society not of their own making, Jacko says.

“I cannot work with the seasons and pay my bills,” Jacko says. “We are subject to the majority culture that says we have to have other responsibilities. How can we practice these lifeways, which is our birthright, and live in this other culture? In the White culture, you have families who have been able to build their assets for many generations. If a parent has accumulated wealth they pass that on to their children. We don’t have that, but we are in a place now where we can start doing that.”

He says there is no other choice if his people are to continue to grow in numbers and thrive.

Besides the financial side, Jacko says there is a clash of cultures when it comes to hunting and fishing which are both government-regulated activities that require licenses and include designated areas and specified times of the year.

Rodwan says one of his goals is the continued purchase of land that can be set aside free of regulations for Tribal members to hunt, fish, and forage. The Tribe currently has about 1,000 acres of land set aside for these activities that stretches as far north as Grand Rapids and south to St. Joseph with the largest concentration being in Calhoun County.

“I try to get property that is zoned for open space because you can’t have a traditional lifestyle without the land,” he says.

Restoring what was lost

Rodwan says the foods that are part of a Native American diet never went away totally, but the re-capturing of those foods will take time and knowledge and the ability to successfully merge the contemporary world with the old ways.

This involves the selection of heritage varieties of plants and the pesticides and nutrients to manage the growth. Many of these plants are being grown in a 6,000-square-foot hydroponic greenhouse and on adjacent land that’s tucked away on the Pine Creek Reservation.

Under the watchful eye of Greenhouse Manager Steve Wherry, lettuce, tomatoes, swiss chard, and a variety of herbs are grown and harvested for use by the tribe and for area schools, and to a lesser extent the Fire Hub, a restaurant and food pantry, operated by the NHBP. Outside there are areas where corn, squash, and wild blueberries, and strawberries grow.

“Each year we expand the footprint of our food sovereignty,” Wherry says. “This year we brought in chickens that are kept in the back of the property.”

The focus of much of the work on the property centers around the restoration of habitats with naturally-occurring food on them, Rodwan says. Among these are corn, squash, beans, and a sugarbush that annually produces between 25 and 50 gallons of maple syrup that is supplied to restaurants at the FireKeepers Casino and to Tribal members.

Rge sap from these maple trees was originally used as sugar that remained usable for extended periods of time. Traditionally, it was among the first foods of the year for Tribal ancestors, Rodwan says.

“All year the ancestors would try to stockpile food for the winter and if they made it through the winter they would get the first foods which are maple sugar and syrup,” he says.

There are currently about 150 maple trees, most of which are on the reservation that are part of the Tribe’s sugarbush inventory. Rodwan says this variety of tree grows well in this area of Michigan and more are being planted to create a staggered population that could lead to the production of more maple syrup.

Among the trees that have not fared as well are Black Ash.

“Black Ash trees were used to make the baskets, which were a very important commodity for the Tribe,” Rodwan says. “We don’t have very many of these trees left in southern Michigan.”

Central to the food sovereignty effort is adapting to the environment that’s currently available using traditional methods, which means that not everything that was lost will be regained.

“We don’t have what we need or the previous generations to get it back to the way it was,” Jacko says. “But, you cannot have a cultural heritage without understanding your own foods and how they are cultivated. Primitive lifestyles were gathered around food. Anytime people gathered together that’s when events were happening. We’re a culture that passes on knowledge verbally.”

Among these events were Wild Rice Harvests which Jacko says were “a huge community event because of the large amounts of labor involved in harvesting and cultivating. It takes a lot of effort to harvest. That’s the way it was meant to be.”

Wild Rice Harvest events have been re-introduced and female Tribal members play a major role in preparing the rice for use in Tribal ceremonies and gatherings. This is another example of merging the traditional ways with life as it is now for Native Americans.

“You can’t know who you are unless you know who your people are,” Jacko says. “We don’t belong to a culture, we belong to a local people. Tradition gives you a place to belong. It is critical to our mental and physical health that we know who we are.”