Editor’s note: This story is part of Southwest Michigan Second Wave’s On the Ground Battle Creek series.

A stay at a camp in Dowling has been a rite of passage for students in the Battle Creek Public Schools system for 90 years.

On October 14 this anniversary will be celebrated by the Battle Creek Outdoor Education Center (OEC ) Clear Lake Camp, which is owned by BCPS, with a Community Open House from 11 a.m.-4 p.m. Blake Tenney, Director of the OEC, says he is expecting to see multiple generations of camp alumni among those attending the Open House.

“You talk to people in town and people of all ages remember this place,” he says.

During the school year, BCPS students in grades K-6 come out to the camp’s main 175-acre campus. Here they participate in learning activities tailored to the curriculum offered at their respective schools with an emphasis on science and the environment.

A typical day for residential campers begins at 7 a.m. with a cleanup of their dorms and getting dressed. After breakfast, they do an activity, have lunch, and participate in another activity. Rest hour is at 4 p.m., followed by dinner and all-camp activities.

K-4 students attend a Farm Animal Camp and a Pioneer Cabin Experience during the day while fifth and sixth-graders have the option of attending all-day camps or a four-day residential camp where they stay in dorm-like cabins — one for boys and one for girls — that sleep up to 66 students each. Their teachers accompany them and participate with them in outdoor sessions that include time spent learning about plants, farm animals, and the importance of working together, Tenney says.

Most of the students hosted throughout the school year are in grades 5-6.

“The teachers choose from the activities we offer that range from science to team-building through a High Ropes Adventure Course,” he says. “It just depends on the school’s budget.”

The science-based focus features pond exploration and ways that animals interact in the food chain and how food interacts in the food chain. Students also learn about environmental issues. For instance, a farm up the road from the property had unknowingly been feeding cattle food that contained Polychlorinated Biphenyls (PCB) which sickened the animals and produced tainted milk that was consumed by people.

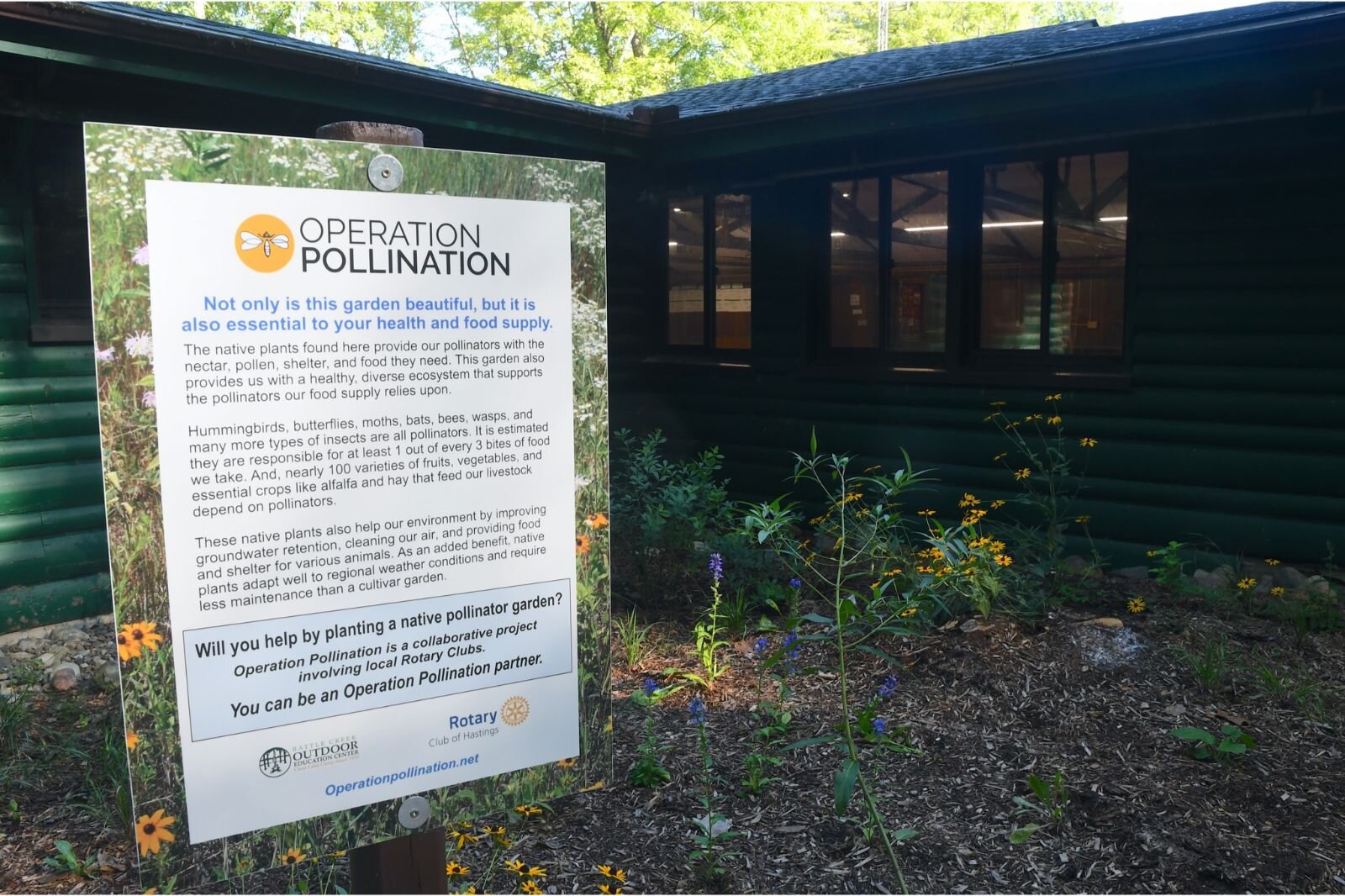

The out-of-doors learning is augmented by sessions in a science building near the front of the camp which has a greenhouse and two classrooms. A large barn houses animals like goats, pigs, cows, and turkeys. The 185-acre lake contains fish, snakes, and amphibians and a Screech Owl greets visitors in the lobby.

Tenney says some of the animals students interact with have been rescued and require extra attention before being released which gives students hands-on experience with feeding and caring for them.

“Little kids get to learn all about that,” he says.

Besides all of the exposure to nature and farm life, students also receive glimpses into the past courtesy of two individuals who assume the roles of “Ma” and “Pa”, owners of a Pioneer Cabin. They demonstrate how gardens were planted in the past, how stews and candles were made, how wood was cut to make cabins, and how root cellars were used to preserve produce.

Miles of trails throughout the property connect students to the buildings on the property and more importantly, to the plants and wildlife that provide spontaneous discovery of their environment.

No child left inside

BCPS students are given priority placement before the OEC facilities are made available to students in other school districts such as Kalamazoo or Detroit. Tenney says the camp also has drawn attention from schools in Chicago.

The average cost per student depends on the length of stay and programs selected. School-sponsored student attendance is paid for by the respective school districts, and the OEC attempts to keep program costs as low as possible by leveraging grants from the George & Emily Harris Willard Trust, the BCPS and Wheels to Woods foundations, and the W.K. Kellogg Foundation.

“It’s important to me that kids come out here,” says Tenney. “We operate like a public school; we’re a nonprofit organization focused on delivering a high-quality, student-centered learning experience.”

Kimberly Carter, BCPS Superintendent, calls the Outdoor Education Center a “truly invaluable asset. It’s been a pillar of the education experience not only for BCPS students but for countless other schools and programs throughout West Michigan for decades. We are proud to be able to offer such an incredible resource where memories are made each year and passed down from generation to generation.”

Tenney shares Carter’s commitment to ensuring that all of the school district’s students have access to the camp.

“It’s important to me that kids came out here. We don’t have as many assets to offer scholarships. We operate like a public school. We’re a nonprofit and we don’t have endless amounts of cash.”

But, even with the availability of funds to offset the cost, he says for families living paycheck to paycheck, any cost is a “stretch for some of them.” For this reason, Tenney says BCPS has always done what it can to supplement the cost for these families.

The OEC’s annual budget is between $400,000 and $500,000. In addition to 10 instructors, the staff is made up of Tenney, a Programs and Events Coordinator, two custodians, and a groundskeeper.

When not working with students during the school year, they are on-site to make sure things run smoothly for youth attending summer camps offered through BCPS’ 21st Century Programs or private groups like the Lions Club for its Blind Camp for visually impaired adults; the Trillium Twill dance club; a role-playing group called Dystopia Rising; and area football teams and high school bands who hold their camps on a regulation-size football field at the OEC. There also is a house that is available for private individuals to rent.

The OEC also owns another 75 acres across the lake from its main campus. Canoes get students and others across where they can have cookouts and hike around.

Except for the football teams and marching bands, other groups use the OEC on weekends when students aren’t there, Tenney says.

Back where he started

The OEC property was originally owned by the Campfire Girls of Battle Creek — a precursor to the Girl Scouts. In the 1930s the property was acquired by WKKF, which was established in 1930 with one of its goals being the promotion of better health for children: three camps were soon initiated in southern Michigan for that purpose, says the OEC website.

In 1932 facilities at Pine Lake were used for summer camping for children. In 1933 WKKF expanded into winter camping and added to the Clear Lake land, constructed a main lodge similar to Pine Lake’s, and began using the camp during the winter months. In 1937 the Foundation began to use a third camp, St. Mary’s Lake, for winter camping.

In 1966, the name Clear Lake Camp became Battle Creek Outdoor Education, but Tenney says many former campers still refer to it by its original name.

“It’s got a great history. So many people have come here that want to continue to send their kids and grandkids,” he says.

Tenney was one of those kids. He attended for the first time as a 6th grader at Dunlap Elementary School in Pennfield. That initial visit ignited a passion for summer camps. He spent summers at other camps where he held jobs including counselor and staff trainer until he aged out as a specialist. After high school graduation, he attended Central Michigan University and earned a Bachelor’s degree in Education with Minors in Biology, Reading, and Planned Programming in 2005.

Even though he was at different camps, Tenney says he always felt a special connection to the OEC.

“I loved the environment and the experiences I had there,” he says.

With his degree in hand, he made a beeline for the OEC where he worked for four years as an instructor. He then “ran away” to Colorado and worked in the restaurant industry and also taught at the Keystone Science School which focuses on Outdoor Education. From there he spent 12 years in Arizona as an event planner for the National Football League (NFL), National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA), and Fortune 500 companies.

He stayed in touch with staff at the OEC and when former director, Amy Cherry, told him she was retiring, he decided to apply to be the facility’s 9th director.

“I was hesitant to switch career fields, but I had loved this place for so long and so I came back,” Tenney says.

Four months into the job, he says he has no regrets.

“I love being in nature. It’s very peaceful. Out here you’ve got woods, a lake and a pond, an orchard, and a farm program. This is a way of life that’s slowly slipping away from people. It was a great change of pace coming back here. It’s awesome seeing when kids learn something and it clicks.”

Carter says the OEC offers that “powerful blend of nature, adventure, learning, and fun that makes for some of our students’ most memorable moments in school. So many in our community have experienced Clear Lake Camp for themselves as children and have those memories to look back on and share with their children who are now in school, too. I think there’s a familiarity and even nostalgia attached to the OEC in this community, and that’s been a huge part of what has made the program so successful over the years.”

Tenney says people who attended the OEC in the 1950s and 60s share their memories when they come back to visit or volunteer.

Without a place like this, he says students don’t have the experience of immersing themselves in nature and they become indoor children.

“Too many of them stare at their screens all day and then they’re parents wonder why they’re not getting these outdoor experiences,” Tenney says. “It’s a missed opportunity if kids aren’t going to places like ours. The most important thing for me is that they can go somewhere like this to learn and grow and develop an appreciation for their environment outside of the walls that keep them inside.”