Market forces among barriers to overcome as community searches for more affordable housing

When you dig into the causes behind the lack of affordable housing in Kalamazoo County it turns out one of the big ones is there are not enough houses to meet the demand.

This story is part of Southwest Michigan Second Wave’s series on solutions to affordable housing and housing the unhoused. It is made possible by a coalition of funders including Kalamazoo County, the city of Kalamazoo, the ENNA Foundation, and the Kalamazoo County Land Bank.

It’s just the brutal ways of the market: When a thing grows scarce, the price of that thing goes up.

And it’s brutal when it affects something we all need: Shelter. Housing.

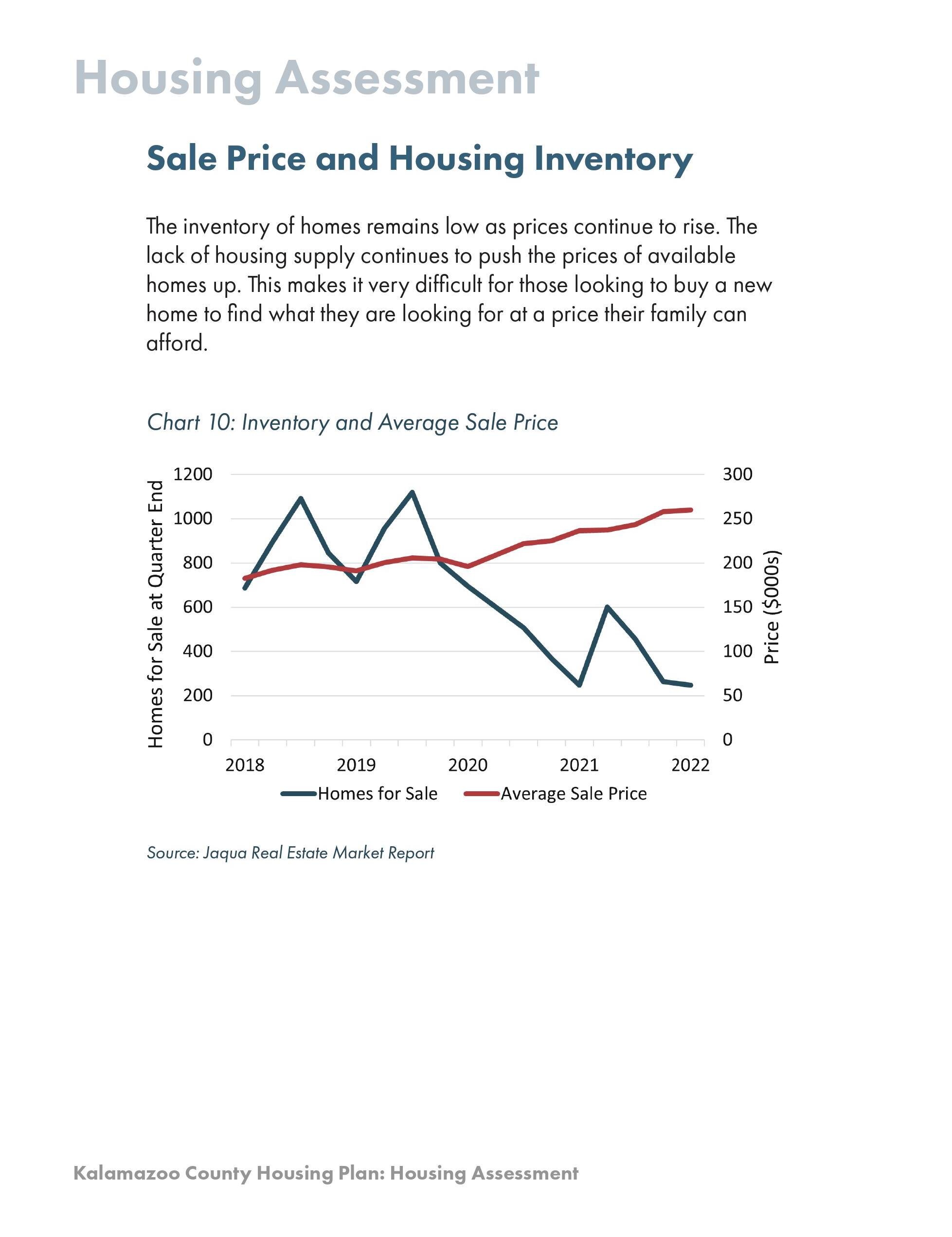

In Kalamazoo County, vacant housing units have dropped from 8.5% in 2010 to 2.7% in 2022, according to U.S. Census estimates for Kalamazoo County.

Median rents in Kalamazoo have increased from $710 in 2010 to $1,085 in 2022 — a 53% increase during a time when overall inflation increased 36%.

The amount of lower-priced rentals is shrinking. In 2019 there were 5,398 rental units going for under $500 per month. In 2022, there were 2,514. Units with a rent of over $1,000 went up from 10,787 in 2019 to 22,342 in 2022.

People renting are finding it very difficult to find an affordable home to own. If they aren’t moving up, and out, units stay occupied.

Blame is scattershot, aimed at everything from general post-pandemic inflation to empty-nesters keeping their too-big-for-two-people homes. Is it that no one is moving and creating vacancies, or that too many people are moving to the county thanks to growing companies like Stryker and Pfizer?

For this report, we heard many explanations for why housing is scarce and expensive. But the solutions to fixing this were all focused on the basic fact that we need to build more housing.

A real estate agent’s view

Marissa Harrington is a Kalamazoo real estate agent who says she believes everyone should get a chance to own a home.

Her perspective comes from growing up housing-insecure in Los Angeles. “I’ve never really lived in a house until I became an adult and could buy one with my husband,” Harrington says. “So I became really passionate about just homeownership in general, specifically for black and brown communities, because that’s the community that I come from.”

Marissa Harrington and her Real Estate team.

She now leads the Harrington Team at Keller Williams. She’s also the co-founder and Managing Artistic Director of Face Off Theatre Company, and mother to two young children and one teen. Luckily for us, she had some time to talk about what she’s seen in Kalamazoo’s housing prices.

Harrington moved to Kalamazoo 15 years ago. Her first job in housing was as a leasing agent for an apartment complex. She remembers that around 2015 “you could get a two-bedroom for $680… beautiful amenities, nice layout for $680!”

Shortly after that she met her future husband who owned a three-bedroom, one-and-a-half-bath house in Milwood. Harrington looked up the house’s valuation, and it came in around $125,000.

They sold it in 2017 for $140,00. “It also had multiple offers. That’s when we started to see the real estate market pick up. We had three or four offers on that house and it was bid up to 140,” she says with a laugh.

Starting in 2018 “we started seeing that happen more and more, so the national economy did what it was supposed to do, which was to encourage people to purchase homes,” she says.

Herrington started her career as a solo agent nine years ago, got her license, then “immediately contacted Kalamazoo Neighborhood Housing Services,” she says. “I really believed in their mission” of helping low-income people buy their own home. “It sounded like a program that, when my mom and I were struggling, we probably could have really benefited from. My mom was a disabled veteran” — if she had something like KNHS in LA, “our situation would have been different.”

When Herrington began her career as a Realtor, she sold homes for KNHS and others in Edison and the Northside for $20,000 to $50,000. “But those communities were also majority renters…. The work that KNHS was doing was promoting owner occupancy in these neighborhoods.”

The mission was “encouraging first-time home buyers that they could purchase a house for $100,000 or less and that it was possible and that home ownership is affordable.”

“I literally built my business on that. And then everything took a turn in about 2018,” she says. The economy was better, jobs were coming to Kalamazoo, and people locally and nationally were encouraged to buy homes.

She saw houses getting multiple offers. Prices were going up, but houses could be found that were still affordable, Herrington says.

“When COVID hit in 2020, we had already been on an upswing of housing, inventory becoming a problem, and housing prices rising…. What the pandemic did was, instead of slowing down the housing industry completely, it did the opposite, which we all were very surprised by — I still am to this day — the global pandemic actually created demand for people to want to buy houses!” she says, laughing.

Herrington pictures a couple in an apartment, “I’ve been in this space with you, staring at your face in a 300-square-foot apartment — don’t want to do it anymore!'”

More people started working virtually, and realized they could live wherever they wanted. “And that, coupled with the government stimulating the economy with these really, really low interest rates — I mean, it was bananas. It was BA-nanas.”

Herrington figures that now that her husband’s old house in Milwood that they sold for $140,000 in 2017 would now go for “$275,000 easy… So you tell me what’s happening with housing!” she says, laughing again.

People aren’t moving

Kalamazoo County Housing Director Mary Balkema, who oversees the multi-million dollar housing millage, says there are many factors behind the spike in housing costs.

Plus, there are factors that worsen the problem.

Living space used to be “about $125 a square foot. Right now, we’re looking at $225 a square foot,” Balkema says.

“Housing costs have increased and the wages haven’t. So we have a gap in affordability. I think that is something that we’ve never seen,” she says.

General inflation is up, interest rates are up, plus “the taxable value of the county and the city is at the highest it’s ever been. So when the taxable value has increased, so has everyone’s tax bill.”

“You know, if your salary hasn’t increased 7% to 9% every year, you’ve lost buying power, right?”

Also, people get very comfy in their old homes when their mortgage interest rate is less than 4%. (As of May 12, average 30-year fixed home loan rates are at 7.09%, according to Freddie Mac.)

People don’t want to move and free up their homes.

“They are not going to move, and then have to get a mortgage rate at a lot higher unless they absolutely have to. And we are dependent upon people moving for there to be inventory.”

Balkema continues, “And I don’t know if interest rates are going to drop back under 5% in the short term, if ever. And so this really might be a new normal.”

She knows of aging families, where the children have moved out, and the parents are sitting in big, empty nests.

“They are not selling their homes, they’re staying there when really a four-bedroom, four-bathroom house should be going to a new family. We should have naturally occurring housing and we don’t.”

Homes for seniors, that are affordable, enough space for two, one floor, in an area where they feel safe and are a reasonable distance to services — “That doesn’t exist anywhere,” she says.

Boomers aren’t moving, and Gen Z, “can’t afford anything,” Balkema says. And there isn’t anything like the “starter homes” of their parents’, or more likely, grandparents’ past.

Incentives to keep a house are huge in Kalamazoo. If one, for example like this writer and his wife, owned a house in the City of Kalamazoo for 20 years, “over time you have grown equity in the last 20 years,” Balkema says.

“But if you were to sell it, the next guy would have sticker shock and all the taxes would uncap, that value would uncap. And someone would get not only a sticker shock on buying your house, but they would get a much larger tax bill.”

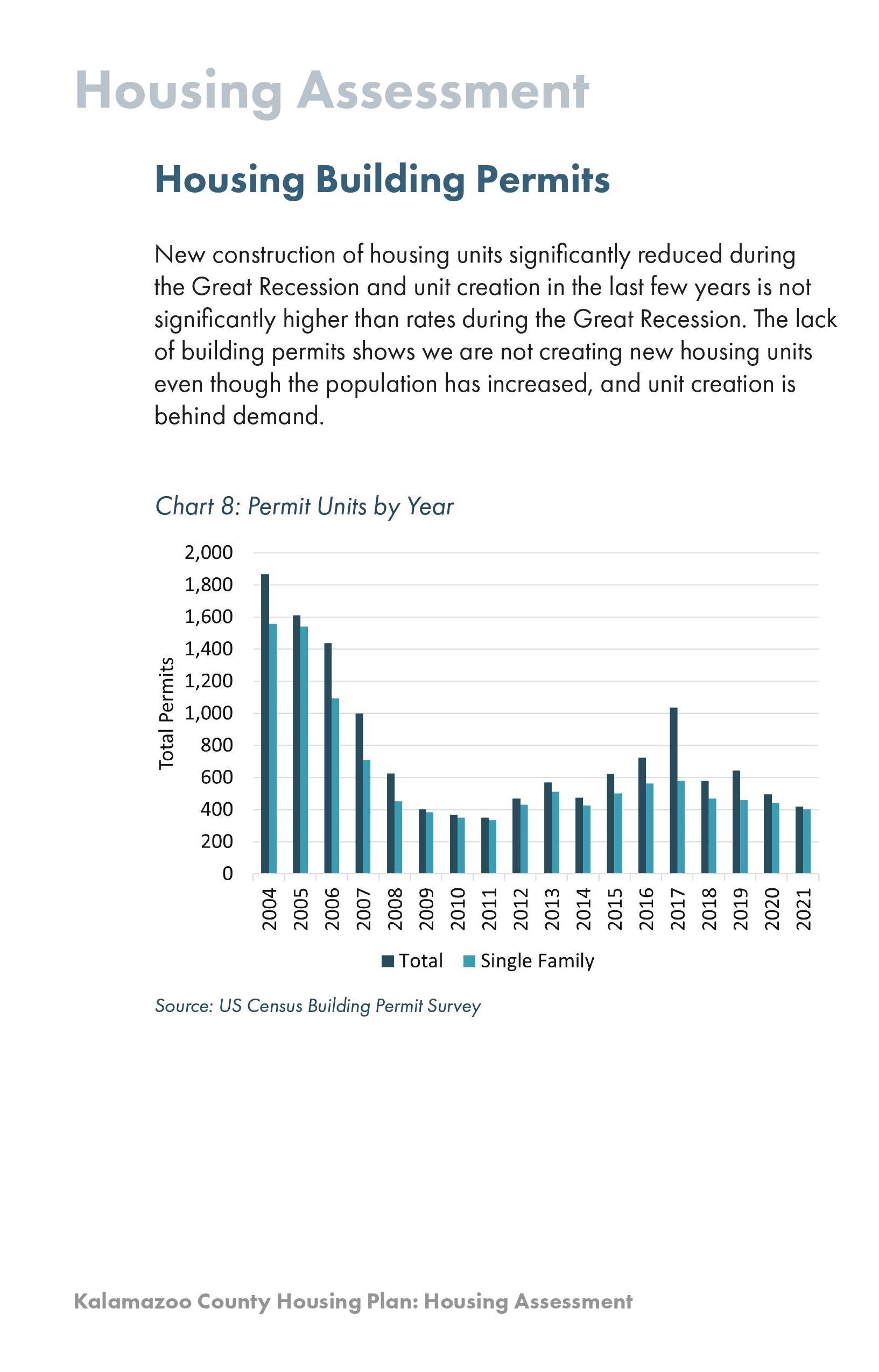

Meanwhile, the number of new homes and apartments needed to meet demand have not been built. “I think the Upjohn study showed that over the past decade, builders were not building at the rate that they were previously because of the economic downturn,” she says.

“So we didn’t have the inventory that we were used to having. During the economic downturn in 2008, people had lost a tremendous amount of value in housing, and we were in a recession and people get nervous.

“So when you get nervous, you’re not going to build a new house. You’re probably going to hunker down and have your savings go up a little bit because you’re not sure what’s going to happen.”

Demand went up, “and then when we came out of the housing recession, (in) our starter neighborhoods like Oakwood or Edison or Milwood, people with higher earnings, earning power, were buying those houses for cash and they were giving bids over the price,” Balkema says.

“I think some of them are out-of-town investors. I mean, if you look at our mobile homes, we have 28 mobile home (parks) in the county. They’re all owned by out-of-town investors,” she says.

Balkema suspects there’s “value stripping” going on at the parks, “meaning they charge higher and higher lot rent, don’t put any money back into the park. And then at some point they’ll walk away when all the value is stripped from it and it’s pretty much in disrepair. “

Investors may have had some winnings, but people looking for a home, not so much.

“And so anyone else who was a lower income, who was even mortgage qualified, lost out every single time,” Balkema says.

Housing migration

Sharilyn Parsons, the City of Kalamazoo’s Community Development Manager, sees housing as an ecosystem.

She concurred with many of the reasons that we heard from Balkema on why housing is so expensive and scarce in Kalamazoo.

New housing builds slowed in 2008 during the Great Recession, population grew, and construction never regained to keep pace, Parsons says.

“During that time people who were in the construction trades moved on,” she says. “You throw in a global pandemic where the trades were unable to work and you are now dealing with what was already a stressed labor force and you’re trying to mend a stress fracture as well as rebuild.”

Also, housing that might’ve been refurbished was demolished. Following 2008, and within the last decade, “there was an abundance of homes that were demolished, as stated as blight, but they were just demolished and not restored or salvaged or retained,” she says. “The Land Bank now is the owner of these vacant lots.”

Sharilyn Parsons, the City of Kalamazoo’s Community Development Manager

Obviously, it’s a problem of supply and demand, she says. What is known as “housing migration” — where people move as their life circumstances change — isn’t happening.

A young single person might be fine in a studio apartment, then they find someone and become a couple, and need a larger place, then start a family and look to buy a home. “If I’m in my starter home and… now maybe my family has increased or maybe my job has increased and I’m ready to move to the next home — typically people will move in between three to seven years,” Parsons says. “If there’s nothing available for me, I’m going to stay put.”

“But if there’s something for me to go to, then there’s a natural recycling of housing units that are available happening. If there’s no availability, there’s no recycling of existing units.”

“And all we can do is build more units so that A, we have units for people to go into and B, that we create opportunities for units to recycle,” Parsons says. “And if we’re not building and we’re not being sensitive to a sort of an overall housing strategy, then … we lock people in place, ergo, we continue to stymie the housing market.”

Solutions?

In a March City Commission meeting, Parsons outlined all the new units that have been built or are being built. She included units from those for extremely low income, (for one at 30% and below AMI, the maximum rent for a studio apartment should be $529, she says ) to the luxury units of The Exchange.

The building has opened up 152 units downtown — but how are luxury apartments going to help people with 30% AMI get shelter?

Parsons explained at the meeting that it’s all about migration. People who can afford the apartments will move out of their homes, freeing those up for people doing a bit better, and so on down the line. “‘OK, now I can afford to go here, so I’m going to go here.’ That opens up this next layer down to be open,” she said in March.

The city is working with partners, making use of Kalamazoo County’s housing millage, approving and creating site plans, changing zoning, and working in other ways to get more lower-income housing.

At the meeting in March, Parsons said overall future plans should result in 155 new units, “39 of those units are for extremely low income, 95 of those units are for very low income, 21 of those units are for low-income units.”

In her late-April interview with Second Wave, Parsons says one project is a hotel conversion that should result in 80 units, with 66 for low-income residents.

She points to 530 S. Rose that’s being built, plus other developments for seniors on the horizon, that should expand the choices for people to free up that empty nest.

Zoning adjustments have been in the works since 2018. “We’re in the final legs of that between this year and probably the beginning of next year,” Parsons says.

Traditional lot sizes will be able to feature duplexes, accessory dwelling units, and other structures to house more families than the usual one-lot, one-house configuration. “You could have a single lot that actually could house three families,” she says.

The City has just unveiled pre-approved plans for various dwellings to fit a variety of lot sizes. “We have plans from all the way from the accessory dwelling unit, the cottage, to a three-bedroom, to a four-bedroom,” to various configurations of duplexes.

The plans make it clear to builders what’s possible on Kalamazoo’s many empty lots, plus they save builders a large chunk of the cost. “If the builder doesn’t have to pay for the architectural designs, that’s a savings that can assist in the creation of homes faster,” Parsons says.

Affordable mobile homes

Balkema has been looking for, and working on, getting more housing for the county.

According to an April press release from Balkema’s office, “The ‘Homes for All’ Housing Millage made significant strides in its initial two years, contributing over $13.4 million to housing development and supportive services.

To date, approximately 185 new units have been completed, with an additional 85 under construction, and more than 100 owner-occupied homes have received critical repairs to resolve health and safety issues. Additional projects, including the Mt. Zion affordable housing development in the Northside, and the workforce housing community in the City of Portage, are expected to break ground in Summer 2024.”

One of the county’s latest projects that she pointed out to Second Wave, is to put 10 new mobile homes, built in Indiana, at the Sugarloaf mobile home park in Schoolcraft near Portage.

Willa DiTaranto and Mary Balkema point to new mobile homes they helped make available at the Sugarloaf mobile home park in Schoolcraft near Portage as one way to stretch millage dollars on affordable housing.

More density in urban Kalamazoo is also “an answer,” Willa DiTaranto, Kalamazoo County Housing Project Manager says, joining the interview with Balkema.

“I think that one strategy that we’ve been using with the millage is, we’ve been trying to build new housing for the higher AMI,” DiTaranto says, in the “60% to 120% (AMI) range, because the cost of the subsidy is going to be a lot less to build that than it would be to build housing for a 30% AMI unit, for example.”

The county’s strategy involves “putting in subsidy to build housing that needs less subsidy, so we can get more units, but then we’re also investing millions of dollars to rehab our existing housing stock to make sure that every house in Kalamazoo County is safe and habitable.”

DiTaranto adds, “The more units you get, the more it frees up that naturally occurring affordable housing.”

But the stresses on housing aren’t dwindling. Balkema and DiTaranto remind us that new employment opening up at local companies, from Stryker to even Marshall’s coming BlueOval battery plant, will fill the rare vacant housing.

DiTaranto was the Housing Resource Specialist for the City of Portage last year. She says then, “so many of the families I work with, their rents were getting raised and they can’t afford them anymore, because somebody who works for Stryker will come in and rent that unit for more than what they can afford, or more than what a section eight voucher would pay, for example. And so when you just don’t have the housing there, it kind of crushes what used to be there as affordable housing. It squeezes that market.”

The Upjohn housing study found a “shortage of 7,750 units, that’s all units. And the goal was to have 700 or 800 units for 60% AMI and below by 2030. And with the millage funding, we’re on track to meet that goal if not exceed it. The goal was 125 units for 30% AMI and below.”

The millage has funded 100 new low-income units, Balkema and DiTaranto say, and is on track to meet its goal.

The millage “is working exactly like it was supposed to,” Balkema says.

Herrington asks what else can be done

Herrington says, “How I train my team is, people transact real estate from two different places, either from pain or pleasure.”

Moving into one’s first home or into a nice upgrade is a major, positive, life step. Having to leave one’s home can be painful.

She likes to focus on the positive. “I’ve always prioritized this aspect of homeownership for all. That was not my personal experience growing up…. It was rare — like I saw people that were homeowners, they were, like, rich. But it never seemed like anything that would be attainable for me.”

Like KNHS, Herrington’s team has just started holding homeownership classes for first-time and low-income buyers. “They’re free for the community, we get sponsors from our lender and title and home inspection partners. We get experts to come in and talk about things that people always have questions about when they come sit in with us.”

She and her team are more “relationship-focused, education-focused” than transaction-focused, Herrington says. “How can we educate you to empower you in this home ownership journey?”

But so many in Kalamazoo aren’t empowered, aren’t moving forward on any home journey.

Herrington says with real frustration, about the state of housing in Kalamazoo, “I have an issue personally with driving around in this city that I love so much, and seeing so many boarded up properties. And so many nonprofits and so many resources here, and the houseless population growing. I’m just having a really hard time reconciling it.”

The market is driving up the price of having a roof over one’s head. There need to be more entities working to drive housing costs down, or working to make up for the gap between the price of housing and someone’s low income, she says.

Building new homes, renovating homes to make them livable, acquiring homes to increase vacant stock for low-income people — there’s a cost to that, she points out.

“Can there be enough of us to be OK with eating the cost?” Herrington asks. “Nonprofits are especially positioned to be able to do this, right, because we’re not about profiting, If you’re a nonprofit, you’re uniquely positioned to be able to go, ‘Yep, we’re going to maybe lose money because it costs so much money to build things now or renovate things.'”

This is a costly endeavor, “Yeah, absolutely, but y’all, there are too many people on the street — we could probably have more boarding houses, but, hey, do we live in a community that would support that?

“I’m having a hard time reconciling why it’s still an issue,” she says.

Homeownership isn’t the answer for all, she points out. There’s a problem if “we’re only going to address the people who can work really hard to get into home ownership — but even if you work really hard, if you can’t afford $200,000, ‘Oh well!’ There are people slipping through the cracks, so I think we have to figure out where the cracks are.”

Kalamazoo needs everything from group homes for people who cannot live on their own, to transitional housing for people to get on their feet, and houses for “first-time home buyers who, maybe their max budget is $200,000. There’s some of them that can’t even get up that high, $150,000,” she says.

“I mean you’ll be losing hundreds of thousands of dollars if you try and build a house and then put somebody in it for 150. I get it. But maybe that’s what needs to happen!”

Herrington says “KNHS is doing wonderful work, and they always have,” and other organizations are also admirable for their work, “but we need multiple organizations providing housing.

“I don’t know what the answer is. But I live in this city. I invest in this city. My babies go to KPS. I run a business in this city. I have an arts nonprofit in this city. I am all up and through this city, and I see a lot of blight that I have a hard time understanding.”

Julie Mack contributed data research to this report.