Kalamazoo Lyceum: Intentionality, commitment, communication key ingredients for creating community

Community is where you are and what you cultivate, according to panel members at the Kalamazoo Lyceum. Writer Mark Wedel was there to be your 'fly on the wall' for a discussion on 'Hope for the Community.'

Editor’s note: This story is part of Southwest Michigan’s Second Wave’s On the Ground Kalamazoo series.

KALAMAZOO, MI — One’s community might be created, or one might leave home to find it, or it could be the other people who share your obscure niche interests, or it might just be where you’re stuck.

It’s not likely that a consensus can be formed by a group of individuals who likely disagree on many things, but the Kalamazoo Lyceum panelists and audience shared the opinion that community is wherever we’re all in the same boat — so get to know your fellow passengers and play nice.

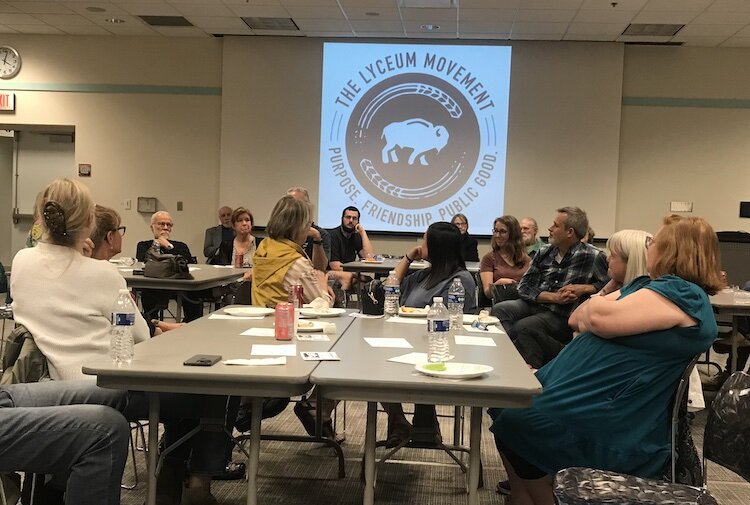

“Hope for the Community” was the topic on April 27 at the Kalamazoo Public Library’s Van Deusen Room. Kalamazoo City Mayor David Anderson, Managing Attorney at Human/Civil Rights Law Center Dr. Kathy Purnell, and founder of The Lyceum Movement Nathan Beacom were on the panel. KPL Community Engagement Librarian Karen Trout led the discussion.

April’s Kalamazoo Lyceum focused on ‘Hope for the Community.’ From L-R, Karen Trout, moderator, Mayor David Anderson, Dr. Kathy Purnell at the Human/Civil Rights Law Center, and Nathan Beacum, founder of the Lyceum Movement.

One might see the Lyceum’s title in two ways: Hope for the community, as in, hope for its wellbeing. Or, hope for the community as this: In a time fragmented by politics, social media, and constantly competing interests, let’s hope we can have a broader community, united by place, shared interests, and shared narrative, here in Kalamazoo.

The panelists focused more on the latter. But first, as Trout asked, we need to figure out, “What does community mean to you?”

Anderson says he grew up in Kalamazoo and went to Western Michigan University during “turbulent times, particularly on college campuses… And I became really disenchanted with what I was doing in college, where I was going, I didn’t know anything about all that. And I decided that I didn’t like Kalamazoo, I didn’t like the structure of how we live together, and I went looking for community.”

He wandered the country and lived in various communes in the early ’70s. He eventually returned to Kalamazoo after having learned, “There is no place to go to find community. There is no beautiful place where community exists. If you want to have community, you need to build it where you are. So that is what community is to me.”

For Anderson, community is, “the intentionality of people wanting to demonstrate that they care about each other… That’s the core for what community is to me, is that people being intentional about the fact that our futures are tied together.”

Purnell is originally from New York City, from parents who came to the city from Alabama and Korea.

Her father grew up in the South, Black during a time before the Civil Rights era. He experienced “more than discrimination, it was racial exclusion,” she says. “And that reality lived with him for a long time, but then he also realized that even in places like that, you do have communities that will support you and will see your value and will mobilize to help you.” Her father relied on family to serve as his community, she says.

Her mother was born in Korea during Japanese colonization. “The whole idea of Korea was very much in question during that time.” After World War II, the Korean War came, and like her father, her mother’s family served as a community, and gave her identity, “a sense of who she was.”

Of her parents, Purnell says, “It’s a miracle that they even found each other and then ended up building a whole new community… but both of them really felt committed to build a new type of community where this biracial, bi-religious experiment could take root, and that was New York City.”

What drew them to the city wasn’t community, it “was opportunity, freedom to just exist without being judged so that they could have an opportunity to find who would support them in life and to help them thrive.”

For Parnell, community is where “we co-create belonging, meaning it’s inclusive, right? We kind of see each other. We have confidence that each of us can influence where we live, to build it together.”

Communities need to face questions, she says: “Is it open to newcomers? Is it a place where people can actually build a life, find work, and build the type of community they want to live in?”

Beacom’s notions of community were part of his reasons for starting a new lyceum movement — based on a 19th-century lyceum tradition of speakers and community members joining together in discussion — in the 21st century.

“Each city that has a Lyceum has its own kind of profile, vibe, and Matthew’s (Matthew Miller, founder of the Kalamazoo Lyceum) been doing a wonderful job in Kalamazoo and that’s exciting, exciting to see how many people have continued to come and enjoy and benefit from these events,” Beacom says.

Community means commitment, says Bascom, but that commitment is likely going to be difficult because “we are going to always live with difficult people because human beings are difficult. And we are always going to live with people who disagree with us,” he says.

“And sometimes if you live with a bunch of people — I don’t know if this was your experience, David, in the commune — who really agree with each other, they actually end up disagreeing more because of the small differences.”

It might be difficult, but communicating with others in one’s community is important, because, “we become well-rounded, we become whole when we encounter people who are different than us. And whether it’s at the local or state level… whether you’re urban or rural or this ethnic background or this political ideology, (one should realize) we belong to the same place and we want that place to do well.”

Community in a fractured era

The next question was on commitment to community.

Purnell added to what Beacom said about living with difficult, disagreeing community members.

She had just taught her first class at WMU in immigration law and policy. Prunell says she had anxieties based on the controversies that surround the topic of immigration.

One assignment was for the students to write an op-ed about the topic. She found that the students were expressing “a lot of anxiety” about it. They realized that “before they wanted to express their thoughts, they knew that there was a lot that they should research, that they should investigate, and that their opinions carry weight. So they wanted to be able to make sure that they did the homework in the background, to make sure that they could communicate with one another.”

April’s Kalamazoo Lyceum focused on ‘Hope for the Community.’ From L-R, Karen Trout, moderator, Mayor David Anderson, Dr. Kathy Purnell at the Human/Civil Rights Law Center, and Nathan Beacum, founder of the Lyceum Movement.

This made her “think about how do we create those spaces where people can speak across different experiences. How do we create those spaces where people are free to learn and grow and not worry so much about being judged about what they say?”

Anderson says that when he became mayor, he thought a lot about how people were becoming more isolated, not communicating, how in “a political space… we don’t get along, we’re yelling at each other, and so on.”

“And I’m gonna propose today that I’m completely flipped on that,” he says. “This story about how we don’t talk to each other, we’re not engaging, we don’t see each other, we don’t spend any time with each other — which granted, certainly did happen more during shutdown time — but that narrative, I really am beginning to feel like is not the case,” Anderson says. “Every day, people are involved in so many things, and there’s so much going on, and so much connection, in my opinion, that’ll make your head spin.”

Beacom disagreed.

He senses that Kalamazoo is community-oriented — though he had just driven here from Chicago, his first visit here.

“I hate to be the Johnny Raincloud,” he says to some audience laughter, “but I’ve had a little bit of a different experience in some different places I’ve lived.”

Beacom had a job in Washington, D.C. (his LinkedIn says he was assistant director of the Regulatory Transparency Project, 2018-2020). He moved from there to live in Lyons, Nebraska, a town of 800 people.

“I went from my lunch break walking past the White House and being like, hmm, do I want sushi, or Lebanese food, or Chinese food, to Lyons, where the only place to get lunch was a flower shop that had an oven in it, and on Tuesdays and Thursdays, you could pay her $7 for whatever she happened to make,” he says.

It felt like two different worlds that did not communicate. “They didn’t speak the same language, they didn’t have the same concepts or narratives of what America is, in many ways, and it wasn’t just between Lyons and D.C., it was Lyons and Lincoln, and Lyons and Omaha, they felt like they were totally unheard, and people in Lincoln probably never heard of Lyons, or many of the small towns across the state.”

There are “shared concerns,” he says, between rural and urban America, “but there’s a lack of trust and there’s a lack of shared language.”

He wanted the Lyceum to be a place for people to simply meet and talk. “We’ve had such a difficult time in our kind of hot-button conversations, where we just walled ourselves off with our kind of preconceived opinion, that if we can get into the Lyceum with people who disagree with us, we can talk about like you (Purnell) were saying, it can be a space to kind of do the homework… and to feel like you’re safe in exploring those, and that’s something that I’ve been very proud to see, is people do feel safe in the environment to do that.”

Beacom remembers starting a Lyceum in Fremont, Nebraska, a “Costco chicken plant town” of 25,000; a Lyceum the mayor predicted people wouldn’t attend, since no one attends the city meetings. It’s a town of houses that, instead of front porches, have large garages facing the streets. “The garages are out front… the structure of the city has blocked us off from being in a community together.”

But people did come out to talk with their neighbors at the Lyceum. He observed, “If you know where to look, there are people who inspire hope, and there’s a lot of activity, dedication to improving place, and local champions, and local community. I think there’s a hunger for local community, but I’m just a little less sanguine on it.”

Purnell says of Kalamazoo, ” I feel like I’m closer to the sources of hope for our community.”

She continues, “I can see the founders of nonprofits every day, walking around in our community. I can see the energy that leads us to create different coalitions to tackle inequalities in our community and different challenges, like with respect to housing, with respect to economic inequality. I feel like I’m closer to the sources of hope, which are our people here, in a way that I didn’t, I couldn’t fully appreciate when I was living in larger cities.”

Trout brings up an essay Beacom wrote in Comment Magazine about online communities versus “communities of moral calling.”

Beacom says, “I think the risk with online community, or what we try to make of online community, is that it caters almost in a consumeristic way to what we already want. So the algorithms feed us things that we already like. If we click on something, we get more of that. We can separate ourselves into, ‘Oh, this is the public forum of all the people who think exactly like I do.'”

He asks, “Are you really in a community if you’re in Tallahassee with somebody in Spokane who you’re never gonna meet?”

He contrasts this with groups like the Rotary Club, chapters around the country that meet in person with an oath to truth, fairness, and goodwill.

“My idea of a community of moral calling is that community is about more than just a shared interest, it’s about a shared life.” These groups establish “a moral framework that says, here’s a way that you can grow beyond what you already are,” Beacom says.

Little League and board games

Trout brings up “geographic and political sorting,” where people seem to self-divide into political/regional groups and never communicate.

Anderson speaks of his duty as mayor to throw the opening pitch for Kalamazoo’s Little League season, “one of the most stressful things I do as mayor,” he says.

“So, hundreds of people there, all different backgrounds, everything volunteer, sponsorships from little businesses, volunteer coaches, beautiful fields, kids all over the place, people coming together, parents of all different persuasions, basically because they want to have their young people to be involved in some positive activities with each other,” he says.

April’s Kalamazoo Lyceum focused on ‘Hope for the Community.’ From L-R, Karen Trout, moderator, Mayor David Anderson, Dr. Kathy Purnell at the Human/Civil Rights Law Center, and Nathan Beacum, founder of the Lyceum Movement.

“Now, are people sitting around and talking politics in the bleachers? I don’t necessarily think so, but in my estimation, it’s one thing to sit down with somebody who you don’t know and start right off talking about what do you think about gun control. It’s another thing to sit down with somebody you don’t know and get to know them as a person.”

Anderson says that as mayor, he’s been invited to events hosted by Black sororities and fraternities, which he’d known nothing about. They “are busy supporting each other and the community, and if you are not connected with that, you have no idea that’s going on.”

He’s become aware of a community of board gamers. A person he works with had moved here from Marcellus and joined a board game club as a way to connect to people in a new city.

It’s “another way to connect, it’s not politics-driven, it’s not intentional about, ‘we gotta get together and talk about things.’ You know how you might play cards with somebody, it’s sort of a construct just to have a conversation?”

Anderson continues, “I think the idea that we can connect first in some way in relationship, you know, and then find the ways that we do agree, which I think there’s a lot of agreement, I think if we keep being in that space, and being open to it, I think we can have some resolution about this, despite the drama we’re all experiencing at a national level.”

Parnell adds that even if it’s something as simple as enjoying a game together, one should “stay curious… stay open.”

She says, “Staying curious about motivations, people, that’s fundamental to keeping that space, for bridging across differences… We can talk about our given communities, ones we’re born into. But we’re also talking about the broader community that can support families and businesses and other places where we gather.”

Beacom says to Anderson, “Yeah, I think what you said, David, is really true that there needs to be a counter-narrative. Even though I think the problem is real, I agree that just bemoaning it is not super useful. And there’s a lot of inspiring people, a lot of inspiring things, in almost, pretty much every town, there’s somebody inspiring, doing something to build a community.”

He continues, “I think what we need to do is talk about politics less, sometimes, and just talk about baseball, or talk about, you know, ‘Settlers of Catan‘ or whatever.”

There need to be more non-political activities and institutions, Beacom says, “because that’s where we build connections across differences.”

Purnell points to nonprofits’ efforts to take on “complex issues together across different political divides.”

“So many of them are in the work of building up our community and recognizing the variety of needs in our community,” she says.

Anderson says of engaging with a wide variety of people in the community, “It’s my job to do that as mayor.”

He speaks about people not coming to “a boring city commission meeting,” so that’s why the city reached out to residents at public events to develop Imagine Kalamazoo 2025. The city should be out again, because “we’re in the process of building Imagine Kalamazoo 2035, which is this idea of what is our current vision and how is that going to form our choices over the next 10 years.”

“It’s an imperfect process,” Anderson says of the city’s efforts to seek public consensus on the city’s development, because once the actual work is underway, “sometimes people flip out about it. And once it’s happening, they couldn’t hate it more. And then I hear about that all the time in emails.”

Building bridges through simple communication helped turn a lawsuit into cooperation, he points out. The City and County of Kalamazoo were fighting over the city wastewater and water system, “which serves a lot of out-county areas, the city system, there was a big lawsuit about that.”

Officials met on the issue, “We got to know each other, we have resolved that lawsuit, we now have a 40-year contract, so this issue is off the table now.” This evolved into regular meetings with Kalamazoo Township supervisors, to discuss shared issues.

Anderson adds that he discovered that a scavenger hunt was happening downtown on the same Saturday as the Lyceum.

“Who organized that?” he asked a participant.

“Nobody knows,” he says, to audience laughter. “No one knows who organized it, but it’s some diverse groups of people walking around, following that same thing… a community event of people getting together, and no one knows who even organized it.”

He says, “I just feel like it’s kind of built into our DNA,” how people naturally fall into a community.

The discussion continued, with Parnell emphasizing her points on openness and inclusivity, and Beacom “name-dropping” Alexis de Tocqueville.

The 19th-century French political thinker warned that American democracy could erode, because “our sense of responsibility will be limited to the circle of our own personal affairs and our own private business,” Beacom says.

A “sense of responsibility for the community has to be cultivated,” was de Tocqueville’s point, Beacom says.

Discussion

In the Lyceum tradition, the audience is organized into discussion groups.

The group this journalist participated in started with the notion that we have disagreements, but we’re all in it together.

I suggested that community is like the current downtown traffic calming/bike lanes changes, that we might have disagreements, but we share the same space, that drivers, bikers, and walkers are all using the streets, and all need safer streets.

This led to disagreements in the group about the bike lanes (it looked to be three for, two very against, two others withholding their opinion). We managed to turn the heat down and agreed on one thing — that the arrangement of bike lanes between parking and the sidewalk on Michigan Avenue makes things difficult for people with mobility issues.

A couple of participants spoke on how they worked to help immigrant communities get their lives going in Kalamazoo. In some cases, “they were brought in overnight almost, taken away from what was home to them and now brought into an area where it’s bewildering to them in terms of navigating even simpler things,” they said.

In the case of a group of Afghan refugees, Open Roads donated bikes so they had some transportation, since it would take a while for them to get a driver’s license.

However, the Afghans needed a place to store the bikes during the winter. Congregation of Moses donated space at their synagogue for storage.

The refugees were Muslim and had never known Jewish people. “And for the first time, they actually had a data point where the men had a positive impression of Jewish people because it was an act of service,” they said. “You build community in ways that are kind of surprising.”

Postscript: The New York Times, the “kumbaya industry”

A journalist for The New York Times was in the audience.

We chased him down after to ask why is he at the Kalamazoo Lyceum.

Jonathan Weisman says it started when he wrote a story for the Times on Silverton, Colorado.

In early 2020 the town of 600 people, “came apart at the seams over Trump and politics. And literally, the mayor had to leave town because of death threats and all these things,” Weisman says.

The town managed to pull itself back together, hold meetings, and talk over its problems,

“I decided I wanted to do this, I wanted to kind of have a side beat, not on writing about the disintegration of our society, but on efforts to pull people back together,” he says.

There’s a “kind of burgeoning kumbaya industry,” he says, of organizations trying to bridge divides, meet, and talk.

He knew of Nathan Beacom and the Lyceum, so he came to Kalamazoo’s Lyceum. (Also, “My wife is actually from Kalamazoo… she went to Norrix.”) The next stop for Weisman is the Rural Urban Exchange of Kentucky, where Kentuckians from inner city Louisville and rural areas meet to talk.

The piece may take a few months to work on, he says, “just put together a story on this burgeoning effort to actually try to figure out how to get people to talk again.”