Editor’s Note: This story is part of our series, Sacred Earth which examines the intersection between climate change — and faith, worldview, philosophy, psychology, and the creative arts. This series is sponsored by the Fetzer Institute.

KALAMAZOO, MI — Planet Earth — it’s the only one we’ve got.

So why does it feel like an overwhelming task for individuals to make the changes necessary to save it?

The Kalamazoo Lyceum discussed “Hope for the Planet” on August 2. It was a lovely Saturday afternoon, but the Kalamazoo Public Library’s Van Deusen room was nearly full.

Panel participants Mia Breznau, (Kalamazoo youth activist, Michigan 2023 Youth Climate Leader of the Year), Ben Brown (environmentalist, activist, and an early innovator of Kalamazoo’s tiny homes movement), and Sister Christine Parks (Congregation of the Sisters of St. Joseph) talked about the beauty of nature, the pain of seeing it vanish, and what to do about its destruction.

Should there be greater activism and protests to try to change a polluting society, to stop and reverse climate change? Can individuals create an impact by living a more sustainable life?

Connection to nature

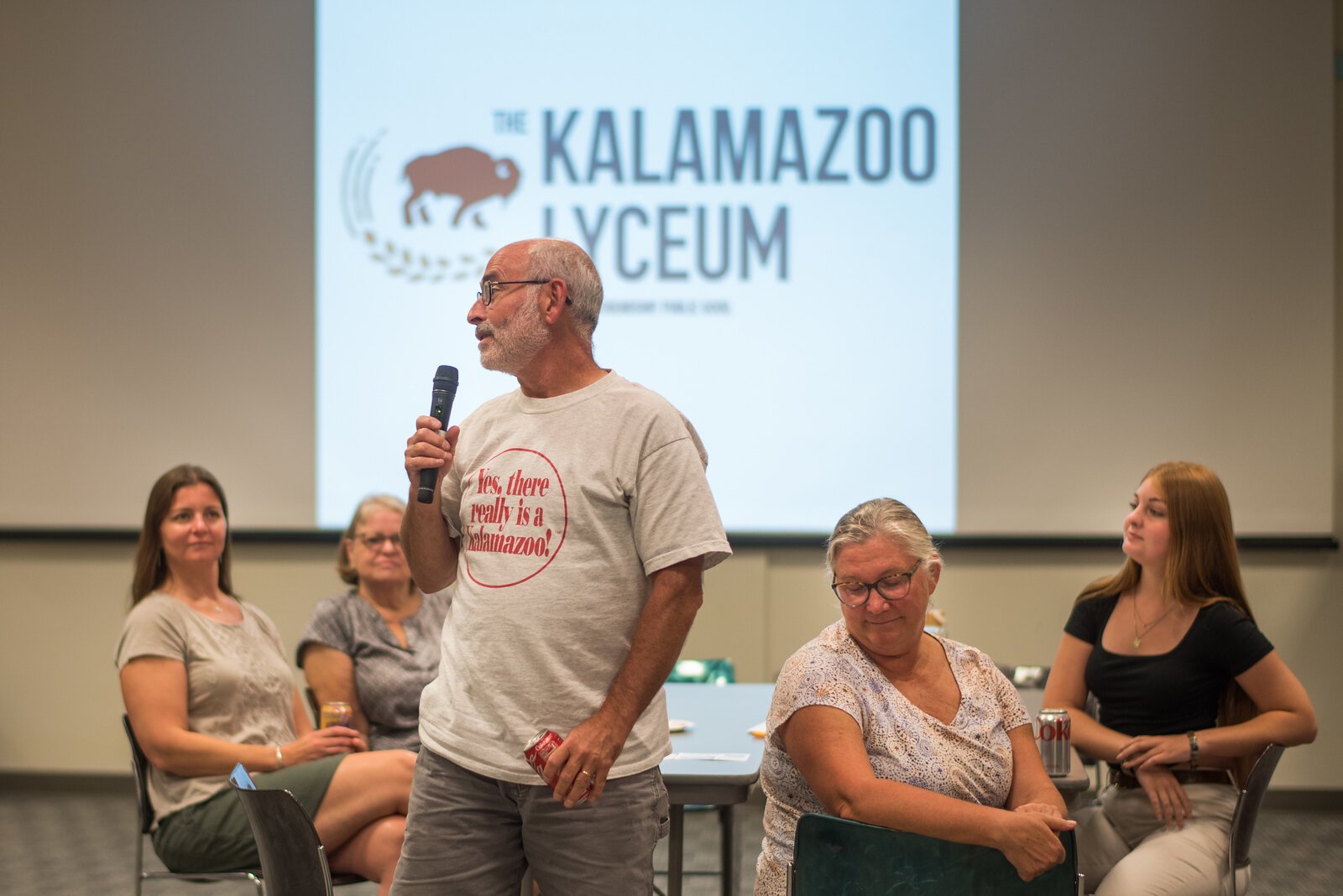

Lyceum host and founder Matthew Miller opened with what became a recurrent theme of the talk, that contact with the natural world leads to one caring about its destruction.

Moderator Matthew Miller speaks about the Kalamazoo Lyceum and introduces the panelists.

Miller spoke about visiting his grandparents, and running off to a semi-natural area nearby, “sneak in through people’s backyard so that we can go run through the water, catch minnows, look at frogs, and just have a good time. It was the most serene place that I can remember as a child, and what in some ways just built my appreciation for the planet.”

Breznau talked about her love of the Kalamazoo Nature Center and local preserves. She’s been on family trips to Appalachia, or snorkeling off the coast in Puerto Rico. But the KNC is top of her list, she says.”Something about the forest there and how big those dang trees are. There’s just an energy there that I haven’t really felt anywhere else in the Kalamazoo area.”

Brown grew up on a farm where, “You could see a five-mile radius around us, because we’re kind of in a bowl, and we could look up. And that diversity of habitat was really neat because you could see orchards and fields, pastures, and forests. And it was just really neat to see a system that had become quasi-sustainable, that had existed for over a hundred years at that time.”

The August Kalamazoo Lyceum drew a packed house to the Kalamazoo Public Library’s Van Deusen Room.

He remembers “swamp tromping” as a child. “In the spring, when the peepers first came out, first started croaking and peeping, I used to love going into the pond, which my mom really did not like because she thought I would go right into the pond and not return. But, it was just all the different plants, the different animals, creatures.”

Parks says she’s a “lifelong Michiganian.” She had spent a few years in Indianapolis, Indiana. “It was a lovely place to be, wonderful people,” she says, but “there was something in my heart and soul that said, ‘This is not the geography you belong to. I’m not a Hoosier.'”

She brings up the KNC, plus the 18 preserves of the Southwest Michigan Land Conservancy.”Their nature areas are very, very near and dear to my heart, and I love walking in many of them. Especially I like going to Bow in the Clouds because once upon a time that was our congregation’s property, which we deeded over to them in the interest of keeping that area preserved.”

Reflection

Miller asks the panel about “the power of reflection.”

Parks says, “When I think about reflection, in a sense, reflection is listening. It’s a deep listening. For me, it’s a deep listening to the world around me.”

Panelists Ben Brown and Sr. Christine Parks

“In particular, I love listening to the sounds of nature.” Parks talks about hearing spring peepers, as the “most exciting moment of spring.”

Hearing tiny frogs, or any natural sounds, is important for Parks’ moments of reflection. “It’s not just a reflection for the sake of reflection, but it really is the taking in and the listening to what’s going on around me, listening to what’s going on inside, and then finding a way to, finding a way to let that deepen,” Parks says.

Brown thinks of his mother, and how she had to deal with “12 kids on the farm at home.” After dinner, she would spend time sitting outside to “just look at the beauty of the evening.”

He was around five when he asked if he could sit with her.

Panelist Ben Brown greets a Kalamazoo Lyceum attendee.

She asked, “Do you think you could be quiet for a couple of minutes?”

“I think my first response was, ‘No,’ ” Brown says to the audience’s laughter.

But he managed to be quiet and sit with his mother. “And that was the first time that I learned to listen and to actually look outside of my thinking to see the beauty around me, and have a sense of something greater than myself in nature,” he says. “That was probably the spark that reminded me that to listen, you may hear more than words and may get a sense of meaning.”

Breznau says, “Slowing down, reflection, pondering, is not something that’s very common in my teenage life. However, that being said, that doesn’t mean that I don’t practice reflection.”

Mia Breznau, Kalamazoo youth climate activist and KalamazoMia Breznau, Kalamazoo youth climate activist and Michigan 2023 Youth Climate Leader of the Year.

She had to write a personal statement essay to apply for college this summer. Breznau thought about a summer learning experience at a marine biology field station in the Bahamas. It had a profound effect on her, “one of the most beautiful landscapes I’ve ever seen, those reefs. So much color, so much life, so much diversity, so many things going on.”

She compares that with a Key West snorkeling trip with her family. There, the reefs were “almost completely bleached and dead.”

Breznau, though she’s about to turn 19 and hasn’t had a long time on this planet, says it made her think “I have witnessed climate change in my own life.”

She thought of other trips where, at Glacier National Park, “we really didn’t see any glaciers,” dead forests in Colorado killed by the emerald ash borer.

Later in the panel, Breznau spoke about “climate anxiety.”

Climate anxiety, activism

Miller asks, aside from being reflective, how does one answer questions to oneself, such as “What am I doing in this world? How do I relate to the things around me?”

“How do you straddle that pressure of this national or worldwide global challenge (of climate change), while at the same time being present at the local?”

Brown replies with a laugh, “Do you have an easier question?”

Panelist Ben Brown speaks at the Kalamazoo Lyceum.

Brown says he thinks back to his family, how “when my parents first moved to Southwest Michigan to my grandfather’s farm, my dad couldn’t get a job in the foundry. There were problems with discrimination, and so my mom organized a bunch of people to write to their local congressperson and help encourage the business to hire my father at the foundry,” Brown says.

“There’s such a push to say, ‘You as an individual don’t matter.'”

Corporations have a greater impact it seems, “but you’ll never believe this — there are people in corporations.”

With enough people, and enough pressure, “we do make a difference,” he says. “A single raindrop does make a difference in the ocean. Take away all the raindrops, there is no ocean,” Brown says.

Kalamazoo Lyceum founder Matthew Miller, and panelists Mia Breznau and Ben Brown listen to panelist Sr. Christine Parks thoughts on Hope for the Planet.

“When I think about addressing climate change, I’m addressing it on a personal basis, but at the same time, trying to encourage my neighborhood, my community, my city, my state, my nation, to also do things,” Brown says.

Breznau says, “The whole individual versus community action is an issue that is kind of hotly debated within the climate community.”

Should a person go beyond recycling or burning less gas, and organize?

“They both do good, right?”

Breznau says she thought a lot about this as one of the youth climate leaders of Ardea. “We’re a group of high school students from across Kalamazoo that kind of just work for climate action within the community,” she says.

Ardea arose out of Heronwood, the KNC’s education facility that teaches conservation to high school students.

Panelist Mia Breznau speaks with attendees.

She’s found studies that show, “The absolute best remedy cure for climate anxiety and depression is taking action. There is no better way to cure climate anxiety than to take action.”

But what kind of action? On the individual level?

“Okay, I’m going to start recycling. I’m going to stop buying single-use plastic. I’m going to ride my bike everywhere. And, you know, the list goes on, right?”

A better step would be to organize and find belonging in a community taking action, she says. “The only real cure to climate anxiety is community organizing and community action. That’s definitely one of the biggest things I’ve learned over my two years at Ardea and over my journey of being a climate activist, is the importance of finding community and really just how much good you can do as part of a community.”

Ardea did a protest and a march of mostly teens in downtown Kalamazoo last September. This led to a lot of comments that protesting is “not going to do any good,” and Breznau’s “first hate comments” on Instagram.

The August Kalamazoo Lyceum drew a packed house to the Kalamazoo Public Library’s Van Deusen Room.

“We didn’t see actual change from that protest, right? We were just a bunch of kids marching around with signs,” she says.

“You know what did happen, though? We felt empowered. The energy at that protest is unlike anything I’ve ever felt before.”

Organizing and protesting helps participants form connections and grow a movement, she points out.

“You’re going to be able to help them form those connections, and ultimately you’re going to help them be able to continue to do action in the future, and that is what is really going to help us solve climate change.”

Sacrifice

Miller brings up the subject of sacrifice, in the context of priests taking vows of poverty and living among the poor.

“Just how much sacrifice is important to our existence as humans, where we have these comforts and conveniences throughout our entire lives, especially in this modern moment that we live in now? And to make a sacrifice, whether it pushes against our social system, whether it pushes against consumerism, especially when we talk about the climate movement?”

Sister Christine Parks of the Sisters of St. Joseph converses with a table of Kalamazoo Lyceum attendees.

Parks says, “For me, a starting point is that making a sacrifice is a choice. It’s not something that can be forced on you. I mean, if it’s forced on you, it’s not a sacrifice.”

Getting rid of “a gas-guzzling car” or recycling might be a “small thing,” but can lead to some inconvenience, she says.

“And so it’s a question of how much am I willing to inconvenience myself for the greater good?”

Her congregation gave land away to become the Bow in the Clouds preserve. The land could’ve been sold and developed, so “in one sense you can say it’s a sacrifice, and in another sense, it’s really a gift. And maybe that’s another piece of sacrifice that to truly sacrifice is to make a self-gift. I’m making a gift for the greater good. I’m making a gift to the future,” she says.

“One of the things that breaks my heart is the thought that future generations of young people are not going to have the experiences that I had, that some of us have had, in the beauty of the world,” Parks says.

“If my gift of time, of energy, of resources, can contribute to a greater good, then that’s a willing sacrifice.”

Brown says, “I think there’s bad sacrifice. I think there’s also good sacrifice. I think I look at sacrifice as liberation.”

He lives in a 230-square-foot house and has long driven an electric car. “Economically, I’m liberated because I can pay this off in a very short period of time. My tiny house, my electric car — It helped pay the down payment for my house because it used so much less (money) to drive it.”

Brown was inspired by Doris Janzen Longacre’s 1980 book, “Living More with Less.” “For me, living in 230 square feet, that was not really a big sacrifice for me.”

However, it took about 30 years of work for him to “have a home so that it would consume less of the planet so that other people could live better — that was a sacrifice of love.”

He doesn’t “necessarily count it as a sacrifice” because “I appreciate this world. I appreciate the people in it. I appreciate trying to slow my impact down.”

Miller looks at sacrifice as liberation, that one could be “able to liberate oneself from the systems that we adopt or view as normalized.”

Panelist Ben Brown listens to the respective toasts from each table.

Miller turns to Breznau and mentions that she and Ardea have gotten concrete results, such as when they got Kalamazoo County to sign onto the Urban Bird Treaty, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s program for bird conservation in urban and suburban areas.

“We came to a Kalamazoo County Commission meeting, and we had speeches, and we got to stand up at the podium and stare into all of their scary faces sitting behind a giant table and present our speeches about why we cared about this issue,” Breznau says.

“I think putting ourselves in that situation of being a little uncomfortable and feeling a little out of place, and then having it turn out so well, again, gave us that sense of empowerment to continue our work later in the year,” she says.

Community and finding common ground

Miller asks Brown what went into his effort to build tiny homes in Kalamazoo.

“Community,” Brown says.

He realized he couldn’t do it by himself. Brown went to Habitat for Humanity, and the Kalamazoo City government, and found “people that I did not remotely expect to come out of the woodwork initially that befriended me, that were interested in trying to make housing more accessible to people. So I am not directly involved with all of the tiny houses that are coming on, but the city used me as a guinea pig, as a template, to see could this be workable, could this be done.”

Brown did research with Sharon Ferraro, the City’s Historic Preservation Coordinator, and found that the homes in neighborhoods like West Main Hill were, at first, tiny.

“People built small houses, but then added onto them over time,” he says. “Today… we think, well, first I’ve got to build a 5,000-square-foot home to start with, rather than grow up to it.”

Kalamazoo Lyceum Founder Matthew Miller talks with Southwest Michigan Second Wave’s Managing Editor Theresa Coty O’Neil.

Miller’s second-to-final question was, what kind of action can an individual take to protect the environment?

Breznau answers with, “the importance of sacrificing some time out of your day to go out and experience nature and the landscape.”

It would be hard to care about something one’s never experienced, she says, “because if you don’t experience it, and if you don’t have that connection to it, how are you really going to care about those headlines?”

Parks says, simply, “Talk to people.” She points to Katharine Hayhoe’s book “Saving Us,” on the importance of communication during the climate crisis.

“Her research showed that there are many, many more people who care about the climate crisis and who care about having a better world, having a sustainable world, but people don’t talk about it because they don’t know or they’re afraid of what might happen in that conversation,” Parks says.

Attendees from each table offered a toast after the discussion.

We should “look for the common ground with people… We all care about our children, our grandchildren, our nieces, our nephews. We care about a particular piece of the landscape that’s near and dear to us.”

Brown says that he agrees with that, but needs to add that one should “make space to have conversations with yourself as well. Journaling, to me, has reminded me so often of what I do value, what I do cherish, and why I cherish it.”

Miller asks what’s become the traditional last question of the Kalamazoo Lyceum, “What is giving you hope these days?”

Breznau says, “Being outside, always. And quite frankly, Biden stepping down. That gives me a lot of hope.”

Brown says, “Seeing all of the electric cars on the street. It used to be 13 years ago when I was driving, I would be really odd. I’m not as odd.”

Parks says, “My sense of hope is grounded in my faith. It’s grounded in my faith in what I would call the holy, the sacred…. It’s a deeper hope than the ‘please don’t rain on my picnic,’ the shallow hope that we often engage in. It is a hope that there is a longer view, and it’s a hope that’s not reliant on the outcome.”

Parks continues, “It is reliant on connecting with people and that critical mass, and what some call a morphogenic field, and I’m not going to try to explain that to you, but it is that sense of, what do we feed? Do we feed the positive, or do we feed the negative? And so for me, hope is part of feeding the positive energy.”

“More important than money.”

After the panel, the audience was organized into discussion groups.

The group I was in had one member struggling with employment, retirees, volunteers with local environmental groups, and others, all above the age of 50.

Following the discussion period, toasts were offered from each table.

Nature is “more important than money,” the unemployed person says. “I think about how poverty impacts people’s relationship to the environment and what they care about because they’re either just trying to survive or… it’s not the first thing in their thoughts.”

The group looked back to the 1970s environmental movement, when “there wasn’t the same type of urgency. Things have changed rapidly in the past decade.”

They’ve seen in their lifetimes how weather patterns have changed, local blueberry crops are ready to pick three weeks earlier, and winters have a lot more snow. Though this area of Michigan hasn’t been hit too hard, it’s obvious there’s a problem.

But it’s hard to know what to do on an individual level. “It’s frustrating when I think of something on that scale, like how do we fix this? It’s like, okay, I’m going to recycle my stuff and I’ll ride my bike, but there are times when I need to pick up something from Lowe’s and I’m going to have to take the car,” one person says.

“It’s easy to do nothing because you can’t be absolute. Or because it’s so big,” another says.

As is tradition, each discussion group had to form a toast to the rest of the Lyceum.

Western Michigan University Professor Steve Bertman offered the final toast from his table’s discussion.

Our group’s freewheeling discussion was wrapped up in our somewhat scattered toast to the audience: “What happened to the snow?” and how older folks are impressed the younger generation, that “they’re just waiting for us old folks to get out of their way so they can get in there and change the world.” And though “money makes the world go around,” what’s important is connecting with others. “Money is less important than connection.”

Other groups toasted to nature, to the youth and local environmental organizations, and to ideas to combat climate change, such as planting food forests and electrifying everything that burns fossil fuels.

It was hard for all to have a say in the time allotted, because, as Miller noted, “This is one of the most highly attended lyceums that we’ve had, and I think that speaks, one, to the importance of the moment, but to the hearts of the people that are here.”

It was to be the last Kalamazoo Lyceum of 2024, but Miller says there is a new discussion series coming. “We have a big announcement coming up” on Sept. 7, he emailed Second Wave. “I want to keep the details mum until then, but it will include a multi-partner event series across several months.”

Stay tuned.

Following the discussion period, toasts were offered from each table.