Kalamazoo’s Blueprint for Peace offers collaborative, comprehensive Gun Violence Intervention plan

While Kalamazoo's gun assaults are down, gun deaths, especially among youth, have risen. The Kalamazoo Community Foundation, in partnership with the City and many others, is launching Blueprint for Peace, a program that addresses systemic factors that drive gun violence to create a framework for prevention, intervention, and healing.

Editor’s note: This story is part of Southwest Michigan’s Second Wave’s On the Ground Kalamazoo series.

Gun violence overall in Kalamazoo is down, the KDPS stats say, but it didn’t seem like it this past summer. A couple days after our interview with KDPS assistant chief David Juday, there was another shooting on Cameron Street, on Sept. 22, making it the 16th investigated homicide this year. This broke the records of 2020 and 2021.

Gun violence feels all too common when you hear the gunshots, and then see the police and ambulance lights arrive at a spot a few blocks down the road.

On the night of Aug. 26, a man was shot a few blocks from this writer’s home. Marcell Savon Alguarelles-Bell, 24, was gunned down on Stockbridge Avenue. He later died.

I saw the same lights down Cameron in the same area a month before, July 23. Another man dead in my neighborhood.

July 23’s murder “was actually the second homicide scene that day for me,” KDPS Assistant Chief David Juday says. The first one was on the Northside, Woodbury Avenue. Juday was getting ready to leave for the day when he was called back out for reports of a person down in Edison.

“I was supposed to be going home, and that was the second person I’d seen shot in the head that day.”

Blueprint for Peace: It starts in 2024, but what about now?

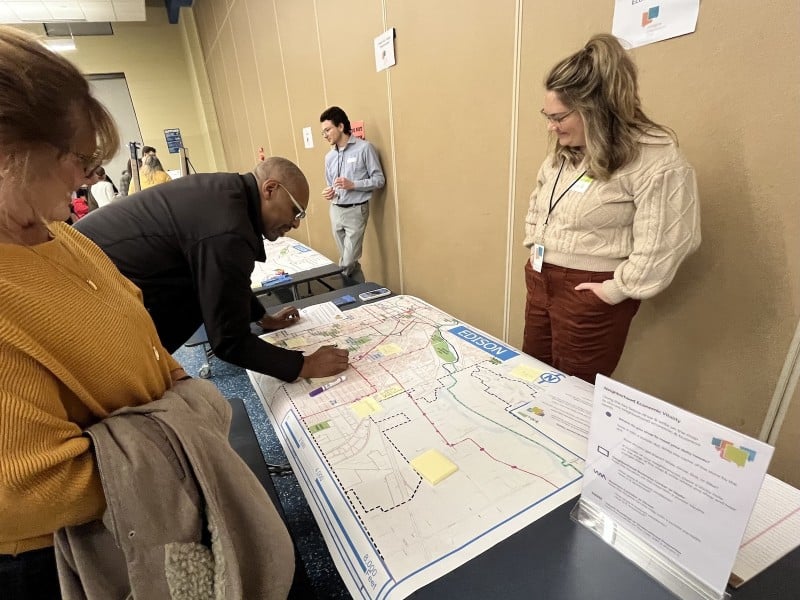

The City of Kalamazoo is now using the Kalamazoo Community Foundation’s Blueprint for Peace as its guide to help rid the city of gun violence. The city is taking grant applications from nonprofits who wish to help in the efforts to reduce gun violence. Grants are to primarily help residents of the Edison, Northside, and Eastside neighborhoods. Deadline is Nov. 3.

Grants will be awarded in January, to kick off year one of the Blueprint.

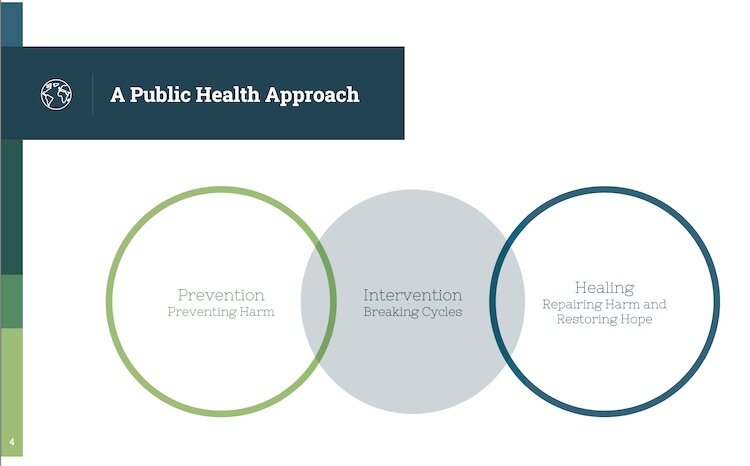

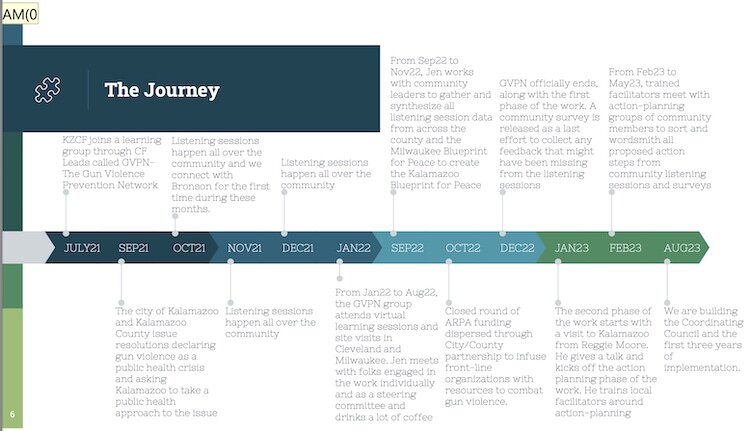

The Blueprint is a three-year, long-term public health approach to gun violence, Jen Heymoss, vice president of Initiatives and Public Policy with the Kalamazoo Community Foundation, says.

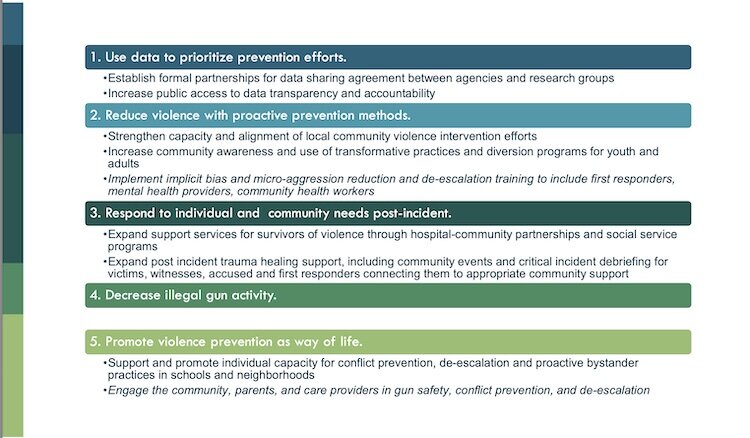

It addresses deeply entrenched, systemic societal problems that contribute to gun violence — trauma, economic instability, racism, lack of education, and more. It all fits in a framework of prevention, intervention, and healing.

The program outlines action steps, she says. One example of an action step is “to promote healthy families and quality early learning for healthy youth development,” to help families get access to “high-quality and no-cost early learning” such as daycare and preschool in these high-priority neighborhoods.

She spoke of what’s planned for year one saying the foundation is being laid. “We are really looking at starting next year, in 2024. A lot of what’s happening is planning for what it’s going to look like.”

Heymoss understands the frustration of people who ask, ‘But what is being done right now?’

“It’s a very long-term strategy that’s looking at these root causes for what’s happening,” she says. “We’re trying to look at long-term strategies, building relationships to share data, (looking at) how do you get different across sectors to coordinate and collaborate, that’s years-long work.

“While we’re doing that, there’s also a shooting in the Edison neighborhood, there’s a shooting in the Northside…. What do we do?”

Heymoss and the Foundation spent the past two years putting the Blueprint together. She came to realize, “I can’t do long term and not talk about how we do intervention right now.

“It’s a crisis. It’s a public health crisis,” she says.

She hears the message, “Convene people about what we’re going to do right now!” It puts a lot of pressure on the formulation and activation of the Blueprint, “but it’s needed.”

Part of her work is to “get people at the table,” including partners like the Upjohn Institute, “the amazing data folks” at the KDPS, and people working at gun violence intervention at the Urban Alliance and ISAAC. It’s a collaborative effort.

GVI, gun violence intervention, is an example of a piece from the Blueprint that’s happening now. It involves work between Kalamazoo police and men who made past poor choices in the community and now want to do good who work with Peace During War. They contact shooting victims, potential shooters, family, and others in the lives of targets and perpetrators, to stop escalation and try to get wrongdoers on a path away from violence.

This work often begins in hospitals after a shooting, so Bronson Methodist Hospital needs to be part of the conversation, Heymoss says. “In order to get people who are on the ground into Bronson, we’re looking at processes, systems. And all of that is not that sparkly, shiny work; that’s all conversations and hard work.”

Peace During War has been doing GVI work since 2011. The work has reached the point “where people who are on the ground, who are doing violence intervention work when a shooting happens, they know the process for how they do violence interruption in the hospital.”

But only a few people are doing GVI, and Heymoss worries that the work “will burn out that one group,” she says.

So a goal for year one — next year — is to form a “community violence intervention training academy that is hopefully going to be a partnership with several different groups in the community.” It will create “a common language about community violence intervention.”

Heymoss stresses “de-siloing” as something that needs to happen. Public institutions and nonprofits have tended to work within their silos when all need to collaborate.

The de-siloing is happening, she says. “The collaboration I see gives me hope… I see things shifting.” People are working together, “and that’s exciting to me.”

She points to a dramatic example of de-siloing, where people who formally never trusted the police, who lived by the rule “snitches get stitches” are now working with the police.

Heymoss points to GVI efforts, where the community and KDPS have been working together to stop gun violence, as an example of “boots-on-the-ground” happening now, before the Blueprint’s year one.

“You cannot arrest your way out of gun violence.”

When Reggie Moore, who leads Milwaukee’s Blueprint for Peace, spoke to a Kalamazoo audience last February, he said, “We can’t piecemeal our way out of this, we can’t say, okay, we’re going to give $10 for violence prevention and continue to give $100 million for cops, courts, and cages.”

Assistant Chief David Juday says that the KDPS found out long ago “that you cannot arrest your way out of this situation. You cannot arrest your way out of gun violence.”

Back during the dawn of the 1990s, when the crack epidemic hit Kalamazoo, “people were getting shot and killed nonstop, there were robberies nonstop, we had huge gang turf wars, we had people from big cities coming into Kalamazoo trying to take over areas and turf. That’s when the community really wanted heavy enforcement.”

Local police had a “tactical response unit” working violent crime scenes during the ’90s, up to as recently as 15 years ago, he says. “You’d have six, seven, eight police officers up there, stop everybody who’s on foot, everybody who’s in a car, and a lot of those people lived in that neighborhood. They were good people. But what happened was, they were getting stopped all the time because our divisional commander is like, ‘Hey, I can’t have another shooting incident on this street.’

“So we went in heavy-handed. And really, we were on a fishing expedition. we were casting a wide net, stopping everybody that we could to try to find out who this individual was… It caused a lot of heartache in the community, and dropped that wedge between the trust of individuals who lived there and officers doing the work.”

Juday says that the police are now combining a “laser-focused deterrence model” using data and evidence to arrest the right perpetrators or find and divert potential shooters. They’re also using community policing and GVI methods to get individuals away from a life where they may be a shooter or a target.

There is still a lack of trust between police and the community, “and that’s been a work in progress,” he says. “Right now I think we’re in a really good spot with our community, we work really well with several of our community members and key stakeholders in our community. But, it’s taken 10-15 years to get to that point where we trust and share information.”

A big help is the former gang members doing GVI work. They do what the KDPS can’t — talk to the young men who find themselves caught up in gun violence.

“Yeah, they can talk to people differently,” Juday says. Of Michael Wilder and Yafinceio Harris, the founders of Peace during War, he says, “When I first started, those guys were at war with each other. I used to chase both of those guys around 20 years ago. And now we work hand in hand together to reduce the gun violence.”

GVI workers have their jobs, but on the scene where someone’s been shot, the KDPS has their own jobs to do, immediately.

“Those scenes are very chaotic,” Juday says.

“Public safety is very unique because we provide police, fire, and EMS service,” he says. When an officer arrives, “and we see a victim down, our first initial reaction is to help that victim.” Medical training kicks in, and saving that life is the top priority.

But there are other tasks the police have to do — preserve and collect evidence and look for witnesses or others who may have been involved. “When you have a chaotic scene with a bunch of people around, you also have to remind yourself about your safety and the safety of others.”

Officers then need to try to prevent retribution by working with the GVI model, along with Wilder and Harris, Juday says.

“When we go out and talk to a shooting victim or a shooting victim’s family, we’re trying to get ahead of the situation,” he says. The big hindrance in this work is that “people in the community don’t want to be labeled as a snitch. It’s not that they’re afraid of talking to the police, they’re afraid of their neighbors seeing them talk to the police. They’re just worried about retaliation, it could be as little as a property crime, or as serious as a homicide.

“If they don’t want to tell us what happened, we look through our databases and social media, and different social network platforms, to find the victim’s or witnesses’ or suspects’ influentials in their life.”

An influential could be a grandparent, football coach, or other person with direct influence in the life of the usually young man involved in a shooting. “And then you explain to those influentials what had happened, or what that individual’s future looks like, whether they’re an offender or a victim.”

Influentials are told, “Hey, this is what this individual’s been involved with, and we understand you’re very influential in this individual’s life. Can you talk to them — because they’re certainly not going to talk to me or talk to my officers — but I just want to give you a little bit of information, nothing in detail, nothing that violates anybody’s — you know, we can’t violate the HIPAA laws….”

“We give them just enough so they can talk to this individual and see if they can see what hurdles, barriers, resources that those individuals need to not be involved in any future incidents.”

The Big Small Stuff

Wilder and Harris tell Juday about “the big small stuff.”

What may be a little frustrating to many — like going to the SOS to get a driver’s license, opening a bank account, or applying for assistance or a job — is “really a big barrier to a lot of people in our society.”

Lack of education, illiteracy, a missing birth certificate or social security card, make such tasks embarrassing frustrations. “They say, to hell with it,” Juday says.

The GVI model helps people overcome these hurdles. “Our GVI coordinator (Wilder) picks up people almost daily and takes them around different places, Michigan Works, Secretary of State, to a counselor’s office, to school, to help those individuals out — specifically individuals involved with gun violence.”

Juday says that a big factor behind gun violence is a lack of education.

Earlier this year he had the KDPS’s data analysts list all youth involved in weapons offenses. There were 50 names on the list. “That’s quite a few juveniles.”

He held a resource meeting with parents, in partnership with the NAACP and its president of the Kalamazoo branch, Wendy Fields, “to see if we can have meaningful conversations with them to see if we can get them the resources that they may not even know exist.”

Then Juday “wondered how many of these individuals are actually going to school.” He checked, and found that “all but two were not registered to go to school.” Around 48 school-aged children were not just skipping, they “weren’t even registered.”

“That is a problem… That becomes a society problem.”

KDPS officers have a lot of duties, but fixing the school system isn’t one. In that case, they can only pass the info on to the city.

Another factor involved in shootings that he can’t fix, is “social media. Parents really need to monitor their kids’ social media,” Juday says.

There’ve been some Kalamazoo homicides and non-fatal shootings involving juveniles over “Facebook beefs.”

It starts when youth obtain guns, and post photos of them online as a status symbol. They then join friends in their neighborhood to take their guns to rivals’ neighborhoods and post photos of them with their guns out in a threatening manner.

“We had it on the Eastside. There were five guys standing on top of a big apartment complex sign, and they all had guns, and they posted on social media.”

A recent non-fatal juvenile shooting this summer came out of the same type of beefs. “They went on Facebook live, they took a bunch of pictures… ‘Hey, we’re on your turf, where you guys at?'” By the time they got back to their own neighborhood, “the shooting started.”

Monitoring social media has become a big part of the prevention of gun violence, in order to intervene before the shooting starts, he says. “The iPhone came out in 2012, it’s not that long ago,” he says. But it’s probably not coincidental, in his opinion, that since then there’s been “a spike in our violence.”

Does GVI work?

The KDPS has the data showing that “not only is violent crime down compared to last year, but assaults with firearms are also down.” The details can be found on the KDPS transparency page.

“Year to date we are down 18%,” he says, in violent crimes from aggravated assault to murder.

Assaults with firearms are also down 18% from last year.

Data analysis is a huge part of the KDPS work, Juday says.

For example, they track juvenile offenses. “If you have two or more police contacts (within 30 days) as a juvenile… your name will go on this list.” The more negative interaction a youth has with the police, the more likely they’ll end up a shooter or a victim.

At the beginning of the year, the report had 14 pages of juveniles. Recently Juday’s been receiving eight pages. At the beginning of the year, some youth have had up to 13 contacts with police over 30 days; now the highest number of contacts has been four, he says.

To the public, “It doesn’t seem like what we’re doing is working, because you open up the social media, you open up the news, it seems like every weekend for a while it’s somebody getting shot,” Juday says. “You see that and hear that all the time, you sometimes forget the silent information that what we’re actually doing is working.”

Juday says he knows of times when gun violence intervention has worked, where “if we didn’t get ahead of the situation or have that intervention, the two groups would’ve continued to feud back and forth.”

Another tool they have is “the custom notification letter.” It’s a letter from the KDPS, saying that “we’ve reviewed your criminal history, we noticed you’ve been involved with some type of violence, specifically with gun violence, and we’re going to pay very close attention to you from here on out if you decide to continue with the gun violence.”

Often, a shooting victim refuses to name the shooter. In the past, the KDPS would close the investigation, Juday says.

Now, their detectives keep the investigation going.

Still, they might not have what they need to arrest a suspect. They can’t “pin them with a gun, but we know they shot this individual. I send community policing officers and some other community resources, and GVI, to their house to talk to them or to talk to their influentials and say, ‘We know they’re involved with gun violence. Here’s a letter showing we’re telling them ahead of time, that if you continue with your gun violence, based on your criminal history, this is what you’re up against. You could be charged on the state side, or with your criminal history, you could be charged on the federal side if you continue with gun violence.”

In the past, the KDPS would only work for that special moment in any police career: “Ah-hah, we got ’em!” he says.

“Now we’re telling these individuals, hey, if you’re involved in gun violence we’re going to tell you we know who you are and what you’re doing, you better knock it off.”

They’re also notifying the person “We know that there’s the potential for them to be a victim. If they’re an offender today, there’s a potential for them to be a victim, because retaliation is really high. We’ve seen a lot of retaliatory shootings — if it’s not at this specific individual, it’s at their house, their mother’s house, their grandma’s house, their friend’s house,” he says.

Friends and family could be hurt or killed. “One thing I always tell kids is, these bullets ain’t got no eyes.”

If they can’t put a person in jail, the next best thing is to use other methods to stop them from committing violence.

Enforcement is “one-third of what we do,” Juday says. Much of the rest could fall under the category of prevention: intervention, mediation, and outreach.

The KDPS, those working in GVI, the city, and society in general need to get ahead of gun violence, “because we simply cannot arrest our way out of it. I could send 25 officers out there and make gun arrests — we make gun arrests every day, but we still have gun violence.”