Road to Healing: Indigenous woman shares her story of surviving Michigan’s Holy Childhood

The Road to Healing Tour is giving indigenous boarding school survivors throughout the United States an opportunity to publicly share stories that many had suppressed out of fear and shame. In honor of Native American Heritage Month, Southwest Michigan Second Wave will feature three of these women's stories.

Editor’s Note: In honor of Native American Heritage Month, we will feature three stories of indigenous women who survived years of trauma at Holy Childhood School of Jesus in Harbor Springs. To address the “troubled legacy of federal Indian Boarding School policies,” the U.S. Dept. of the Interior is sponsoring the Road to Healing Tour as an opportunity for those impacted by boarding school injustices to at long last publicly share their stories. This story from Marilyn Wakefield of Boyne City is the first of three to be published.

Survivor of boarding schools for Indigenous children finally feels free to speak her truth

The psychological torture and abuse Marilyn Wakefield endured as a child did not come at the hands of her parents or a stranger. Her abuser was a nun named Sister Naomi who terrorized Indigenous children including Wakefield who were students at Holy Childhood School of Jesus in Harbor Springs.

Wakefield, 61, is one of a group of four women known as Holy Childhood Survivors who testified in August 2022, about their individual experiences at the school in front of U.S. Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland and Assistant Secretary of the Interior for Indian Affairs Bryan Newland. Their testimony came during the second stop on the Road to Healing Tour which was created by Haaland and Newland to “address the troubled legacy of federal Indian boarding school policies” and develop comprehensive reports that “lay the groundwork for the continued work of the Interior Department to address the intergenerational trauma created by historical federal Indian boarding school policies.”

Since their testimony in front of Haaland and Newland, they have shared their stories with organizations throughout Michigan including the United Tribes of Michigan earlier this Fall. Jamie Stuck, President of the United Tribes of Michigan and Chairperson of the Nottawaseppi Huron Band of the Potawatomi, says their stories are critical to understanding the true extent of the damage these boarding schools did to the children living there, the majority of whom continue to live with those memories.

For Wakefield, a member of the Sioux Tribe, and her fellow survivors — both those like her who are publicly sharing their stories and thousands more in Michigan and throughout the United States who may never speak openly — that trauma never went away.

“Did I see abuse there? Yes. Was I hit there? Yes,” says Wakefield of the six years she spent at Holy Childhood.

She is one of six of 10 siblings who attended the boarding school on the advice of a nurse who worked at a health clinic on Mackinac Island where she and her family lived. The nurse told her parents that there was a “good boarding school in Harbor Springs for Native American children, a good place to stay with food where they would receive a good education.”

Wakefield, who now lives in Boyne City where she works in a gas station, says she knew she would attend First Grade there, but didn’t know where “there” was.

After a journey that involved a ferry boat and bridges to cross, she and her siblings arrived at Holy Childhood where they were told to take their suitcases upstairs to assigned dorm rooms, change into bathing suits, and head to a lake as a way to separate them from their parents.

After that first year, Wakefield says she and her siblings came back home for the summer and didn’t want to return to Holy Childhood in the fall.

“My parents never asked us any questions about how it was living there,” Wakefield says. “We hid every time we had to go back because we knew what we were in for. My mom and dad talked it up to being homesick and that was part of our trauma.”

The appearance of a vinyl blue suitcase signaled the beginning of another trek to the school. Clothes, toothbrushes, and toothpaste were carefully packed, but the suitcase was only seen again once the children went home for the summer.

“We don’t know if they dispersed our clothes to other kids or just kept them,” Wakefield says. “We were each assigned a number and we had to mark those numbers on our underwear, t-shirts, and socks.”

After those summer breaks, the car rides back to Holy Childhood were filled with laughing and giggling. But that stopped when they reached a hill where they could see the steeple of the church on the school’s campus.

“We knew it was going to be another year of hell,” she says. “I thought that the real mission of the school was to kill the Indian and save the white man.”

The hell Wakefield speaks of included forced separation from siblings that extended to the school playground where they weren’t allowed to talk to each other; mealtimes where no one was allowed to talk; and harsh punishments for the most minor infractions.

Privacy was a luxury afforded to no one. Even the weekly Saturday baths found Wakefield sharing a tub with two girls she didn’t know.

The nuns did everything they could to dismantle any semblance of self-esteem with a mission to dehumanize their young charges.

Wakefield has plenty of examples, one in particular that haunts her to this day.

“There was a girl in our dorm who had started her period and she didn’t know what to do or what it was. She would put all of her dirty things in her dresser and before long it started smelling up her area of the dorm and Sister Naomi came up as we were getting ready for bed and she started screaming and hollering at this girl. The girl held her hands over her head and screamed and cried. Sister Naomi just literally melted this girl down instead of explaining.”

The next day, the other girls in the dorm awoke to find the girl’s bed unmade and her belongings gone, says Wakefield

“I believed that they killed her and I grew up thinking that,” Wakefield says. “I found her and she’s still living. She doesn’t know that I found her and she’s listed as Jane Doe.”

On another occasion, Wakefield says she witnessed the nuns smearing the blood from the head and paws of a bear that had been donated for its meat on the faces and hands of boys sitting at a table.

Interwoven among the painful moments she witnessed happening to other students are those Wakefield personally experienced.

“I saw Sister Naomi cutting another girl’s hair and didn’t know I was doing anything wrong,” she says. After she cut another girl’s hair, she says a nun beat her with a green hose.

That nun also made sure that Wakefield was served raisins frequently knowing that she didn’t like them.

“I would put the raisins to one side of my mouth and spit them out where I could,” Wakefield says. “She was mean and crazy to us.”

During summers at home Wakefield and her siblings would talk amongst themselves about their experiences at Holy Childhood, but never discussed what happened with their parents because “who would ever believe us over Catholic priests and nuns?”

Weekly phone calls home were monitored and Wakefield learned not to say anything that would get her into trouble after seeing what those who did complain faced.

“I live with anxiety and depression because of all of this,” she says.

Her brother was severely abused at Holy Childhood and is an alcoholic and her older sister has been in counseling for more than 30 years.

The siblings as adults never talked about what they had endured, but this changed for Wakefield and her older sister about three years ago when Wakefield opened up publicly.

“It flipped a switch in her,” Wakefield says.

Talking to remember

After leaving Holy Childhood, Wakefield attended high school on Mackinac Island and quit three months shy of earning her diploma. She got into an abusive relationship and says this pattern of behavior was the direct result of what she witnessed and endured at Holy Childhood.

She eventually went back to high school and earned her diploma.

“If I’d had counseling back then I could have worked my way through it. I was in a very angry place. I smoked pot and drank a lot,” Wakefield says. “We learned nothing about our culture, language, or what a real family looks like, or how to parent.”

But this didn’t dissuade her from maintaining her ties to the Catholic Church the only religion she knew, or working for the Diocese in Boyne City where she moved for her husband’s job in a factory. She taught Catechism and Truth and Reconciliation classes at a local Catholic church. That ended two years ago when the remains of children’s bodies were discovered along the side of the road near Holy Childhood during a construction project. When that happened, she severed ties with the Catholic Church and now practices her faith in God on her own terms.

“I didn’t give up my faith in God. I gave up my faith in the people working for him,” Wakefield says.

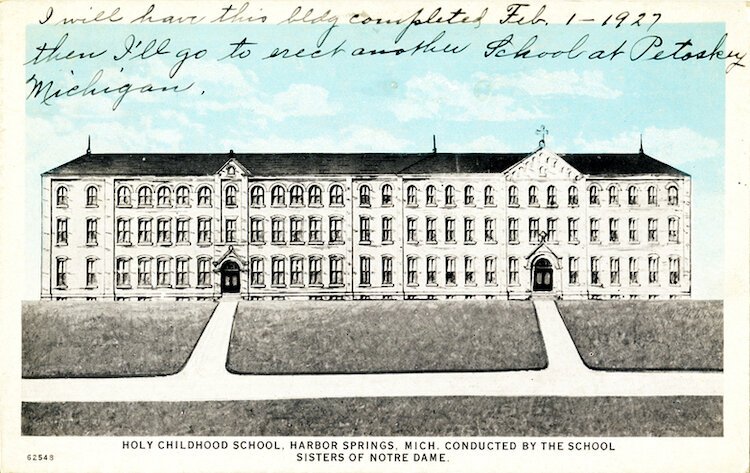

The building housing the school was demolished in 2007. The original school was a mission called New L’Arbe Croche that opened in 1829 but was only open for a few years. This mission school was constructed with the help of Odawa tribes in the area and had lessons in Anishinaabemowin, according to information compiled by the University of Michigan.

Holy Childhood became the first federally run boarding school in Michigan following “changes in federal policy towards Native Americans such as a push for assimilation, federal funding and the Carlisle Industrial School as a model, Holy Childhood transformed and became like other boarding schools. Even with federal funding, there was still a heavy connection with the Catholic Church, as even postcards drew attention to the Sisters of Notre Dame running the school. “

Wakefield asked the Boyne City Diocese administration if they were aware that children had been buried there and received vague responses that “yes, they’d heard something like that” which felt like a betrayal because they knew she had attended Holy Childhood.

What made it worse, she says, was the way the removal of the remains was handled.

The company doing the construction contacted a local tribe and gave them 48 hours to sift through the pile of bones they found, Wakefield says.

Some of those doing the work were mothers with small children who “ended up with PTSD because of that,” Wakefield says. “Harbor Springs should have taped it up and called the police because it was a crime scene. The parents, grandparents, aunts, and uncles never knew what happened to them. There were records from 1913 to 1936 that continue on into the early 1950s, but a chunk of that was missing and those were these deceased children.”

In addition to Holy Childhood which didn’t officially close until 1983, there were similar boarding schools in Mount Pleasant and Baraga. These three schools were among more than 350 throughout the United States, according to the Historical Society of Michigan.

The Road to Healing Tour is giving survivors throughout the United States the opportunity to break their silence and share their stories which they suppressed out of fear and shame. Secretary Haaland’s efforts gave them to courage to step out of their carefully constructed shadows.

“We put ourselves out there. It was such a good relief. It was scary to do the first time speaking openly in a packed gym. I felt such a relief and different people reached out to us. We just want to get our stories out there. We’re the last living set of people in Michigan to get our stories out.”

The sharing of their stories encouraged other survivors of Michigan’s boarding schools for Indigenous children to reach out to them. There is a growing private group on social media of about 107 survivors who connect and find support and the understanding only they would know how to provide.

“The best thing we can do is to get our voices out there so it never happens again, otherwise we’ll be erased. What people are hearing about these schools is 100 percent true,” Wakefield says. “I’m not going to be silent anymore.”