Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

KDPS Chief Thomas says gun violence is doing a lot of harm to families and the community. But the city can have an impact on it if people work together.

Editor’s note: This story is part of Southwest Michigan Second Wave’s On the Ground Kalamazoo series.Michael Wilder says he does not understand the gun-toting murder game in Kalamazoo.

“You just seen Jojo kill Johnjohn,” says the Group Violence Intervention Coordinator in Kalamazoo. “Johnjohn is dead and they caught Jojo. So Jojo is on the news charged with murder. Now Jojo is gone. Why do you follow in Jojo’s footsteps and do the exact same thing to Samsam?

“Now you done killed Samsam and now they got you. And then, why is the next person behind you so eager to do that?”

“Whose winning this murder game?” Wilder asks before immediately answering, “There’s no winners in that.”

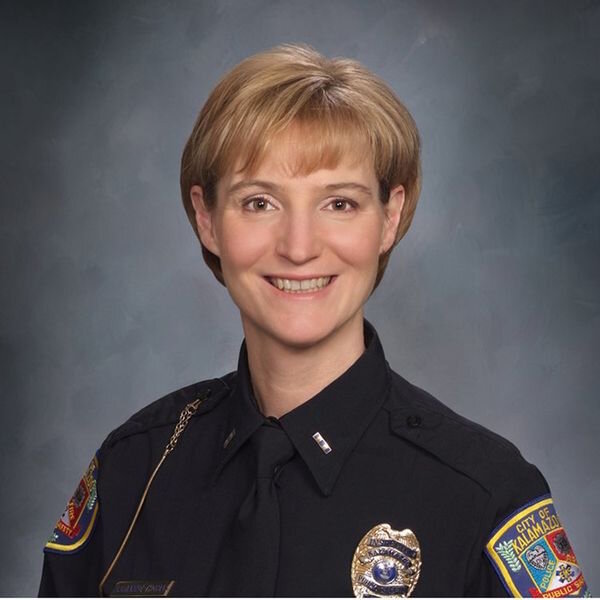

Among those, eight were killed, according to KDPS Chief Karianne Thomas. About half of all those shootings and killings have occurred during the past two months.

“Just since June 1, 23 have been shot and four people have died by gunfire,” Thomas told members of the Kalamazoo City Commission at its online meeting on Monday (Aug 3). And since June 1, there have been 78 shooting incidents in the city, and more than 635 spent shell casings collected by public safety officers at crime scenes.

Mayor David Anderson called it a gun violence crisis “and although cities across Michigan and the nation are having similar experiences, we cannot accept this in our community.”

What is happening?

“Some of them are linked but some of them are just random,” Wilder says of shootings. “Some of them are just people getting into beefs where someone pulls out a gun and starts shooting. Some of them are just people sneaking and doing drive-bys (shootings) and runs-bys (shootings).”

He says that while conflicts over romantic relationships, money and other things may be involved, he estimated that 75 percent of the shootings this year have involved conflicts that started on social media. He doesn’t have statistical data to support that, but he has strong anecdotal examples. Among them is the July 22 evening that two young men were shot and killed in Kalamazoo. Wilder explains that the first shooting occurred about 45 minutes after there was social media traffic between at least two of the people involved.

Dondreal Watkins, 29, was fatally wounded during a 6 p.m. shooting in the 800 block of Woodbury Avenue in the city’s Northside neighborhood, according to KDPS. DeVante Coleman, 28, was shot and killed at about 7:30 p.m. that evening in the 1400 block of Cameron Street in the city’s Edison Neighborhood. A person who had been with Coleman was also shot at that location, officers reported, but did not sustain life-threatening injuries. In each incident, the shooters shot quickly and fled in a vehicle.

Is this gang activity?

“No. It’s not like that. It’s a different demographic,” Wilder says. “If we were in Chicago or Detroit or somewhere like that, yes, we would be able to pinpoint what gang they’re in and we would probably be able to go to their gang leader and say, ‘Hey, are your people shooting somebody else? The feds are going to come arrest you and charge you with murder.’”

“Say you got 12 guys who hang together every day,” Wilder says as an example. “But later on that night, three of those guys go kill somebody. The other nine guys don’t even know what happened and don’t got nothing to do with it. But they hang with them and their name might get put on that murder. And so now all nine of them are targets for the other side when they don’t even really know that their home boys actually did it.”

He says when the police arrest the group and start asking questions, they have a hard time getting answers “because the people don’t really know. And the few that do know, really know how to keep their mouths shut. So they blend in.”

He fears more shootings will occur as young men from the Northside (Woodbury Avenue) and Southside (Hays Park Avenue/Cameron Street) seek revenge for the July 22 killings.

What’s the mentality?

Wilder says there is not one root cause for the violence. In this age of social media, he says feuds have started and been escalated tit-for-tat over things that one person said about another online. He says tensions over those online communications have been amplified by people staying indoors to avoid contact with COVID-19.

Working with the Kalamazoo Department of Public Safety, Wilder says he has been allowed to see video footage from homeowners’ ring cameras — the security cameras that turn on automatically with a motion sensor or when someone rings the doorbell.

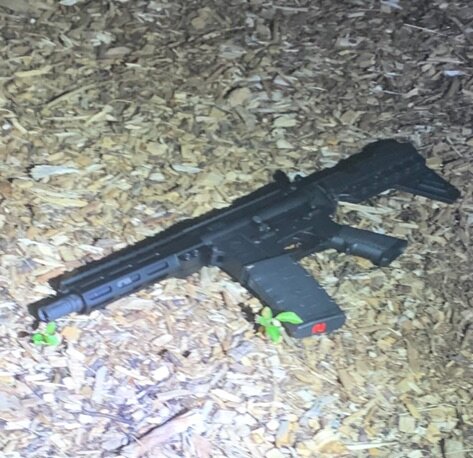

“They’re seeing people, little youngsters, running with hoodies on and Corona masks,” Wilder says. “And they’ll shoot a house 30 times with an AK-47 (rifle) and run away. Or drive by hanging out the car and shoot a house with a .40-caliber weapon 25 times because they’ve got an extended (ammunition) clip in it. And they just keep on riding. They do that. That’s what we’re facing in Kalamazoo right now.”

He says they have been able to amass all types of firearms, often purchased for them by girlfriends, friends or family members who don’t have criminal records and can buy them legitimately. At some point, those guns are reported stolen to shield the original buyers from prosecution if the weapon is used to commit a crime.

What to do?

Sidney Ellis says he doesn’t think there’s any one answer to gun violence. But he would start by talking to children.

“I think a lot of times we try to solve problems with youth that may or may not be a problem,” says Ellis, who is executive director of the Douglass Community Association on Kalamazoo Northside. “We try to figure it out. Or we try to solve it our way without talking to them. My only solution is for us to have a conversation with them, where they communicate with us what they need and what they want. Because we don’t know.”

Of young men who are chasing one another with violence or revenge in mind, he says, “It’s too late to tell them anything other than ‘We love you and we want you to live and not die.’ Some of the people we may not be able to reach, but it’s those younger ones who are following them and looking at them. Those are the ones that I know that we still can reach.”

He says he does not want to sound hopeless or say that anyone is beyond hope, “But there’s probably nothing you can say to someone at 5:30 p.m. that will stop him from shooting at 6 p.m. But what could we have said to them at 9:30 a.m. that morning that may have made a difference?” Ellis asks.

More and better policing is requested

Many people are calling on the city and KDPS to increase policing. “Do your job,” was a statement made to KDPS by more than one person during the City Commission’s meeting on Monday.

Attempts to contact Fields, who also says KDPS needs to stop reckless and high-speed drivers in her neighborhood, were not successful. But her inference appears to echo a yet-uncorroborated story that four suspects were arrested but released after a June 24 shooting that left two children injured. The children, girls, ages 5 and 12, were playing outside when shots were fired at about 9:10 p.m. in the 1200 block of Ogden Avenue, near Douglas Avenue. A bullet grazed the older girl. The younger girl suffered a gunshot wound to the foot.

KDPS officers reportedly found three guns in the trunk of the suspects’ car and spent shell casings on the floor inside the vehicle. But they made no arrests.

Some worry that the suspects were not jailed because law enforcement is trying to keep the population low at the Kalamazoo County Jail to avoid the spread of COVID-19. With courts closed since March for all but emergency cases, and with jails trying to avoid major outbreaks of the coronavirus, Sheriff Rick Fuller has said police are issuing court appearance tickets to all but violent crime suspects and felony drug suspects. That is expected to end as courts reopen.

KDPS has not responded to Second Wave’s requests for comment about gun violence. And attempts to contact Kalamazoo County Prosecuting Attorney Jeffrey Getting about arrests and prosecuting suspects, have not been successful.

The elephant in the room

The talk about how to stop the shootings comes at a time when this community is trying to deal with the COVID-19 pandemic and the nationwide movement to stop systemic racism and police brutality.

To combat police brutality, some are calling for KDPS to be defunded; to have some of its funding reallocated toward programs that help solve underlying contributors to crime, such as joblessness, substance abuse, mental illness, and lack of education.

Wilder says he understands the need to halt racism and stop police shootings of unarmed Black and brown people. But he says the issue of Black men killing other Black men is the elephant in the room that no one is addressing.

Wilder says he knows people care and, “I have seen police officers cry as a result of the senseless gun violence they see in Kalamazoo.” But he says.

most Black people seem to have put in on a back burner while they focus on police-involved shootings.

Shootings among Black males — by other Black males — appear to be on the rise in Kalamazoo’s Northside, Southside and Eastside Neighborhoods, each of which has a significant population of African-Americans. Residents of those communities are asking for more and better policing to stop that gun violence and to stop speeding cars and reckless driving, which some people have associated with the shootings. They are asking KDPS do more serious police work to safeguard residents in the city’s core neighborhoods.

“We need policing,” a Northside man said during Monday’s City Commission meeting. “We need the commission and the Department of Public Safety to step up. They need to step up to eradicate this type of behavior here in the community.”

Without it, he said it’s just a matter of time before residents of the neighborhood react to it “in ways we don’t want to do. So please do what’s necessary. We don’t mind policing in the neighborhood. In fact, we encourage it. Wherever there’s a problem that’s where we expect Public Safety to be.”

But all that comes at a time when the fear of negative repercussions from harsh confrontations in the African-American community have to be in the back of many police officers’ minds.

Bringing people together

At Monday’s meeting, Chief Thomas said gun violence is doing a lot of harm to families and the community. But the city can have an impact on it if people work together.

“Our tools in the criminal justice system are at a standstill due to COVID — jury trials not starting, jail restrictions, and other things,” she said. “But we know what works.”

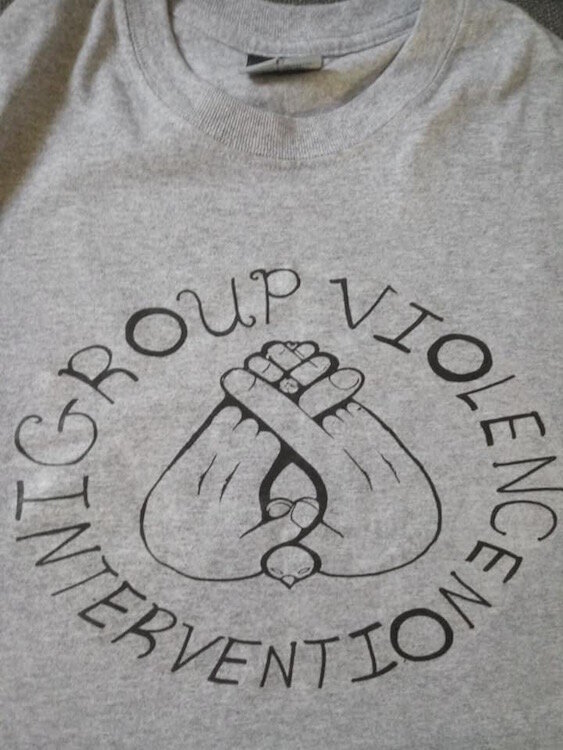

She said she knows that partnering with others in the community works, as do strategic interventions, “like our Group Violence Intervention program where we reduced group-involved shootings by 50 percent last year.”

“We know that we can make an effect even though our tools are limited,” she said. “I think we’re going to pick up some new ones that we can (use to) partner with the community and address this gun violence because it just can’t continue.”

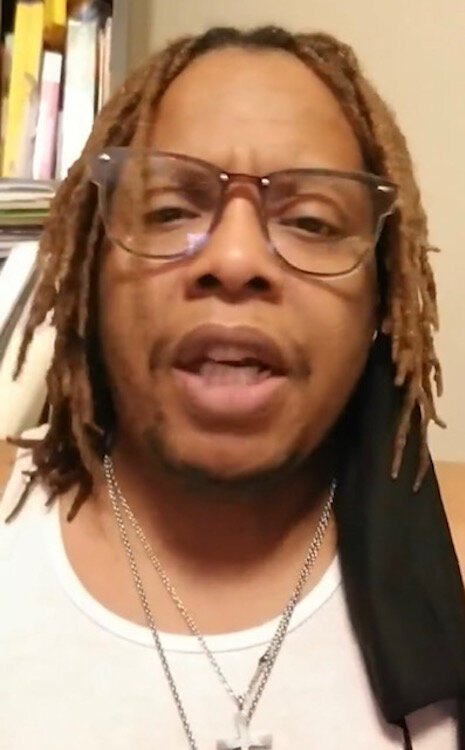

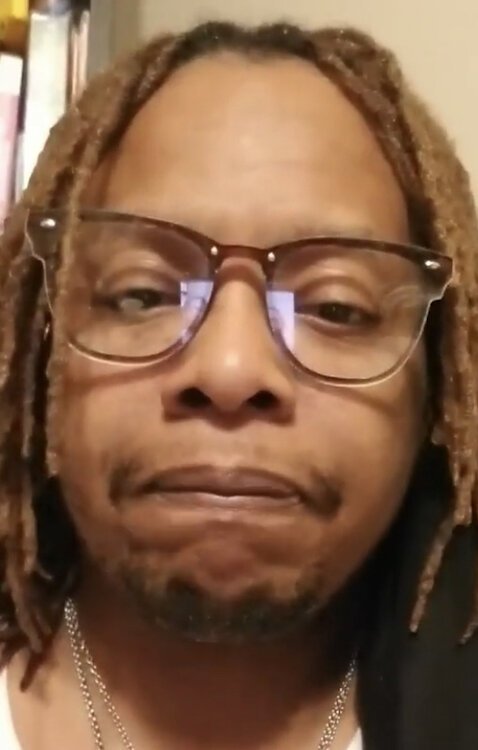

As coordinator of Kalamazoo’s Group Violence Intervention strategy for the past three years, Wilder is called on by KDPS to work with criminal offenders and suspected offenders (accompanied by community members and law enforcement) to try to set them on a path to better futures, and provide resources to help them find jobs and steer clear of other crimes.

A native of Chicago, Wilder sold drugs here in Kalamazoo, was convicted of seven felonies and was imprisoned three times before he found Christianity and turned his life around about 15 years ago. Now age 47, he is married and is the father of two young girls. He also works as a support staff member at Kalamazoo Covenant Academy, an alternative school that helps at-risk young people.

Where things are headed

Ellis says, “Here’s the thing: there’s no one problem so there’s no one solution. There’s no one solution for a multitude of problems.”

In regard to the shooting, he says, “We have to work on the elementary school kids and some of these middle school kids. And as much as we can, work with the high school kids. But how do you reach them? What will you say to them? I don’t know. Another thing is who are they going to listen to?”

He says they might listen better to people who have “been there and done that” than those who have not.

For his part, Wilder says, “Right now, I’m not even trying to get them to stop shooting at each other.”

He says he knows people will frown on that. But right now he says he is concentrating on getting young people who carry guns to agree — in a truce-like fashion — to stop shooting into people’s houses. Some of them do that as an easy way to retaliate against an enemy. But it’s extremely dangerous and cowardly, Wilder says. And they don’t consider they could kill someone’s mother, grandparents, or children.

“We want to make it illegal on the streets to shoot up a house,” Wilder says

Shooting up a house is a part of the murder game he doesn’t understand.

“If you haven’t touched my child, if you haven’t did anything to one of my children, I don’t want to kill you,” he says. “I don’t want to take your life. Why is it that our young people are so eager to take each others’ lives? To throw each others’ lives away?”