Editor’s Note: This story is part of our series, Sacred Earth which examines the intersection between climate change — and faith, worldview, philosophy, psychology, and the creative arts. This series is sponsored by the Fetzer Institute.

The science of the climate crisis has been available for decades. Yet still, many dismiss it as unimportant or irrelevant, even as sea levels continue to rise and extreme weather has become a common and tragic occurrence. How to reach people?

While science appeals to the mind, art can touch the heart. To make change, we need both.

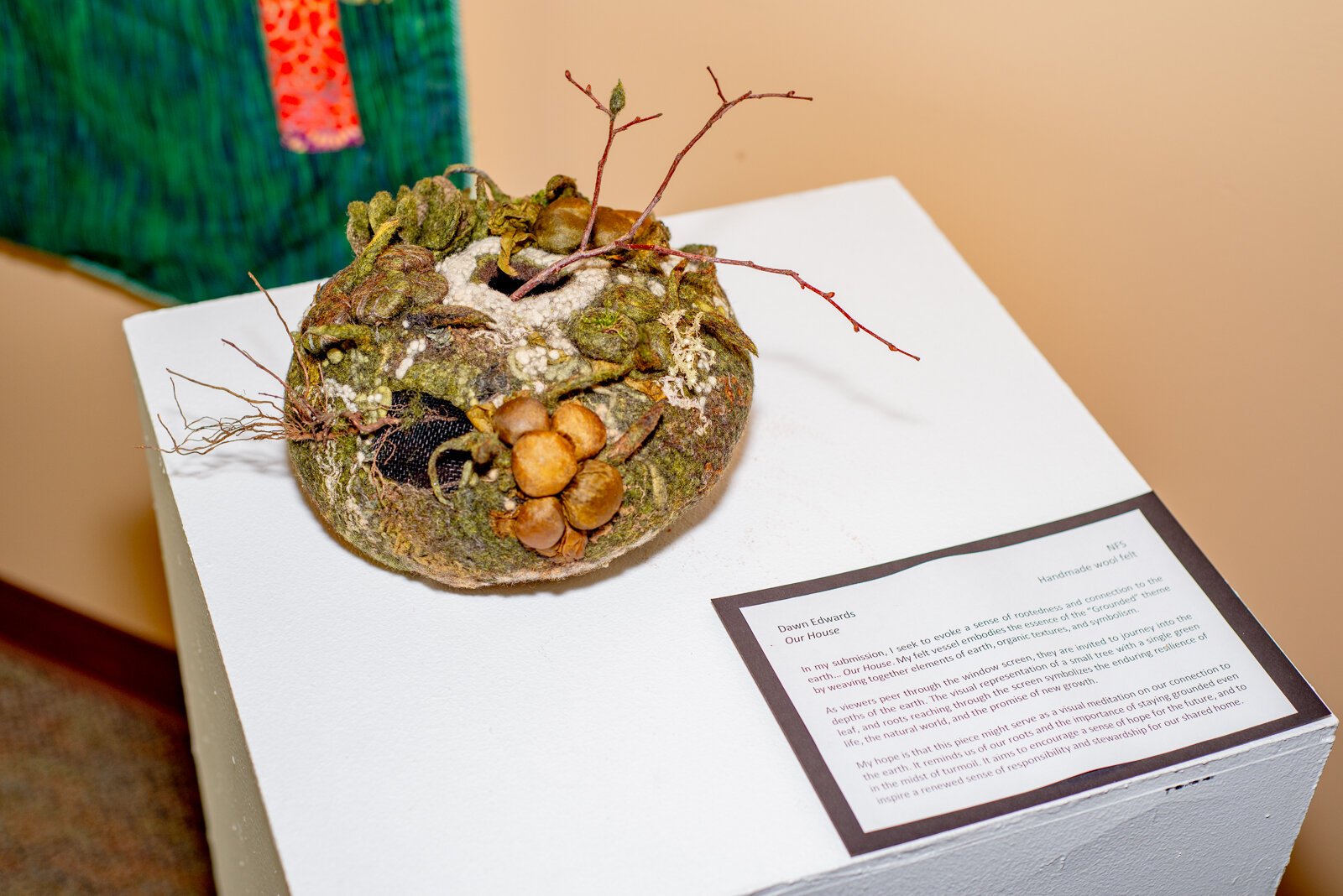

Pastor Jerry Duggins founded the Westminster Art Festival, an annual event at Portage’s Westminster Presbyterian Church to raise awareness of various environmental and ecological issues by reaching the heart and not just the mind. This year’s theme is “Grounded.”

“The Westminster Art Festival started in 2013 with the help of a grant from the Beim Foundation,” says Duggins. “We had a member on the board — Jim McKim — who came to me and said, ‘I have some money I want to give to the church for development of the arts.’ So I developed the concept of the art festival.”

The Westminster Presbyrterian Chuch, site of the Westminster Art Festival

In its first years, the art festival exhibited the artwork of children, kindergarten through 12th grade, as well as adult work, but Duggins and the planning team found the effort to solicit student work challenging and the multiple age categories made the exhibit lack focus. Since 2017, the exhibit has been open to all local artists aged 16 and up, and with all levels of experience, amateur to established.

The environmental angle, Duggins says, “flows out of our sense of faith at Westminster. We have some core values, one of which is the arts and music, and another which is earth care. Those are things that we care deeply about and that gave direction to this outreach.

“The other thing that fed into this is a purpose statement which we call our Intention Statement. Part of that says that we are interested in engaging the world, not on our terms but the world as it is. We view this outreach as an invitation to local artists to participate with us in delivering an environmental message. That flows directly from our sense of faith in the church.”

Remembers.”

This year’s theme of “Grounded,” Duggins says, is meant to focus on land use. Artists have brought differing perspectives on the topic — from the indigenous understanding that land is not a commodity to humankind’s relationship to the earth. While some artists took on the theme literally, others treated it metaphorically.

As the exhibit opened to the public on April 27, 2024, at the Westminster Presbyterian Church, 1515 Helen Avenue in Portage, crowds flowed through doors that opened to blossoming trees and surrounding woods. Janet Duggins, wife to Jerry Duggins and co-pastor for the church, greeted all who entered.

“In 2023, we counted 120 people just on opening day,” she says. She expected this year’s numbers to be even higher.

Attendees were invited to submit votes on their favorite art pieces for a later People’s Choice award. Refreshments awaited as people milled around rooms and well-lit hallways (lighting was installed with Beim Foundation funds) of art in various mediums — watercolor, oil, and acrylic paintings; fabric and textiles; etchings; sculptures and 3-D installations. Each piece is accompanied by an artist’s statement posted beside it to explain the artist’s viewpoint on “Grounded.”

“We received 51 pieces in visual arts this year,” says Conrad Kaufman. Kaufman, himself a well-known landscape and mural artist in Kalamazoo, serves as visual arts juror for this year’s exhibit. Having grown up on an organic farm near Bangor, Michigan, where his parents, Maynard and Sally Kaufman, taught homesteading skills for self-sufficiency, Kaufman brings a unique expertise to his role as a juror.

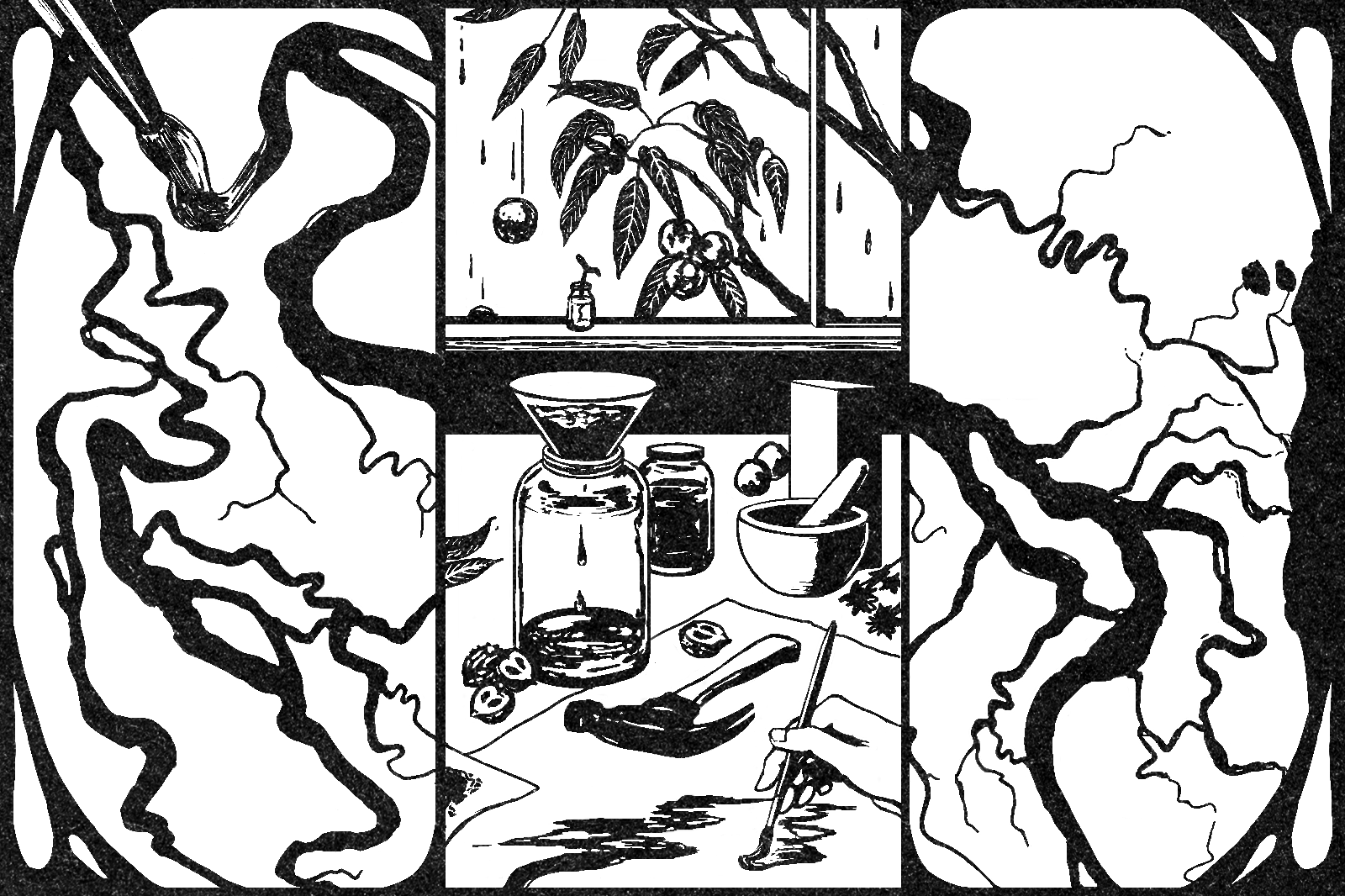

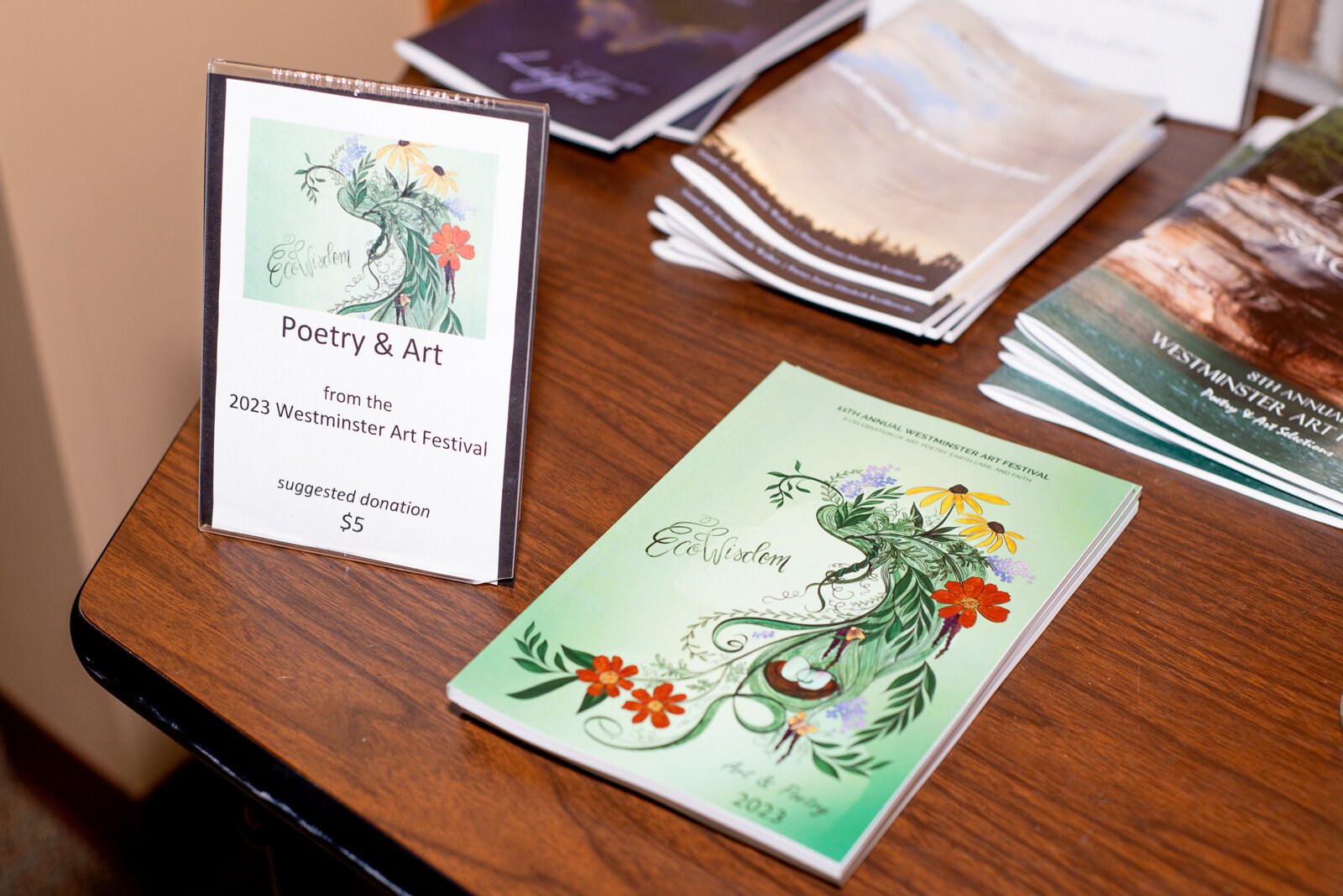

Poetry and art from the 2023 Westminster Art Festival.

“It’s been a joy to do this,” he says. “As to judging the submissions, I considered relevance to the theme. Composition, execution, how well did they express their intention, presentation. And gut reaction — my gut gave me direction when I chose first and second place.”

The spiritual side of art is familiar to Kaufman, who says he regularly walks in the woods when he needs a break from work and the mad, mad world.

“It is not just how we use the land, but understanding that it is a part of us,” he says. “My dad had a Mennonite background, and he wrote a lot about earth-based spirituality. Early Christianity was all about the shepherd caring for the land. Art gives us another voice to express this. The best role for art is to knock us out of the dark, to raise our awareness.”

Kaufman is not optimistic, however, about where humankind is headed in light of the current climate crisis.

“Hidden Connections” by Lorrie Grainger Abdo

“Art can open us with personal expression,” he says. “In my classes, I urge students to spend time simply looking to increase their sensitivity. But the world at large? I’m not convinced that going deeper into our understanding of what is happening around us now goes beyond aesthetic enjoyment. I am pessimistic about our future. I give us maybe 25 years.”

“We can be saved by art,” Anita Skeen counters.

A resident of Okemos, Michigan, Skeen is professor emerita at the Residential College in the Arts and Humanities and director emerita of the Center for Poetry at Michigan State University. She is the author of six volumes of poetry with a seventh due out in 2025. Skeen is the poetry juror for the 2024 Westminster Art Festival.

“I see poetry as witness,” she says. “Art is essential, not decorative. We can change the world with art.”

Skeen believes that art in all its forms can make necessary connections between people that can move the masses to make change. While the brain functions as a combination of reason and emotion, reason is about analytics, but emotion — which can often be stirred by art — can get us moving.

Artist, Vicki Nelson with her piece “Chaco Canyon.”

“We turn to art in a time of crisis,” Skeen says. “I wrote my most recent poetry book during the Covid lockdown.”

Judging the poetry submissions to the festival, Skeen looked for a fresh take on the subject. “I wanted to see imagination,” she says. “I looked at structure, how they used language. The poet must go beyond just description. I read about 30 poets for this competition, with a range of quality. Often the most subtle poems can have the biggest impact. Then I scored them, 1 to 5.”

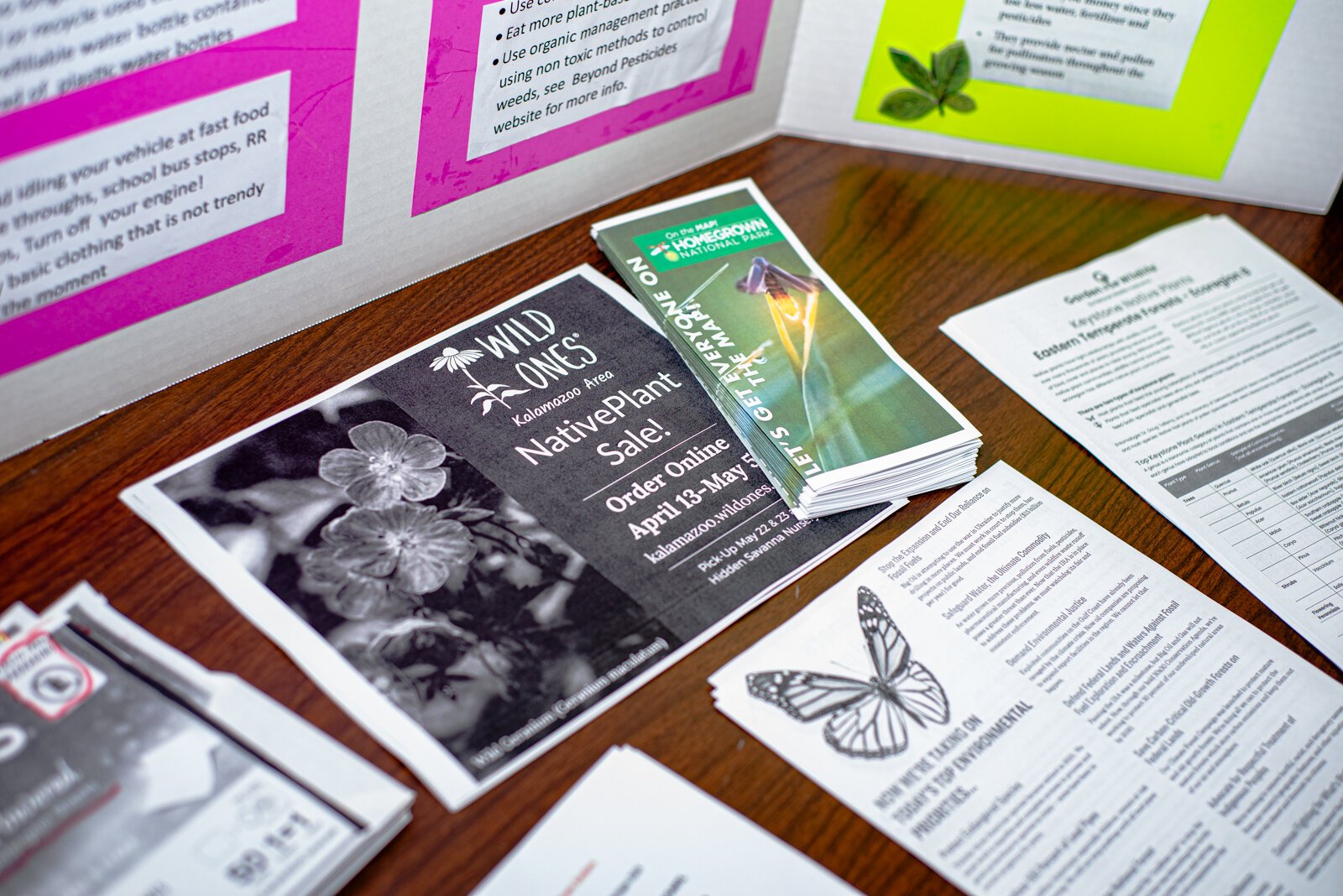

Both visual and literary art eventually make it into a glossy, color publication to commemorate the year, and copies from previous years are sold for $5 at each annual festival with complementary copies to award winners. The commemorative book is arranged by Jerry and Janet Duggins’ daughter, Miriam. Award winners were announced on May 10.

Artist, Jodie Gerard with her piece “Rags to Rugs.”

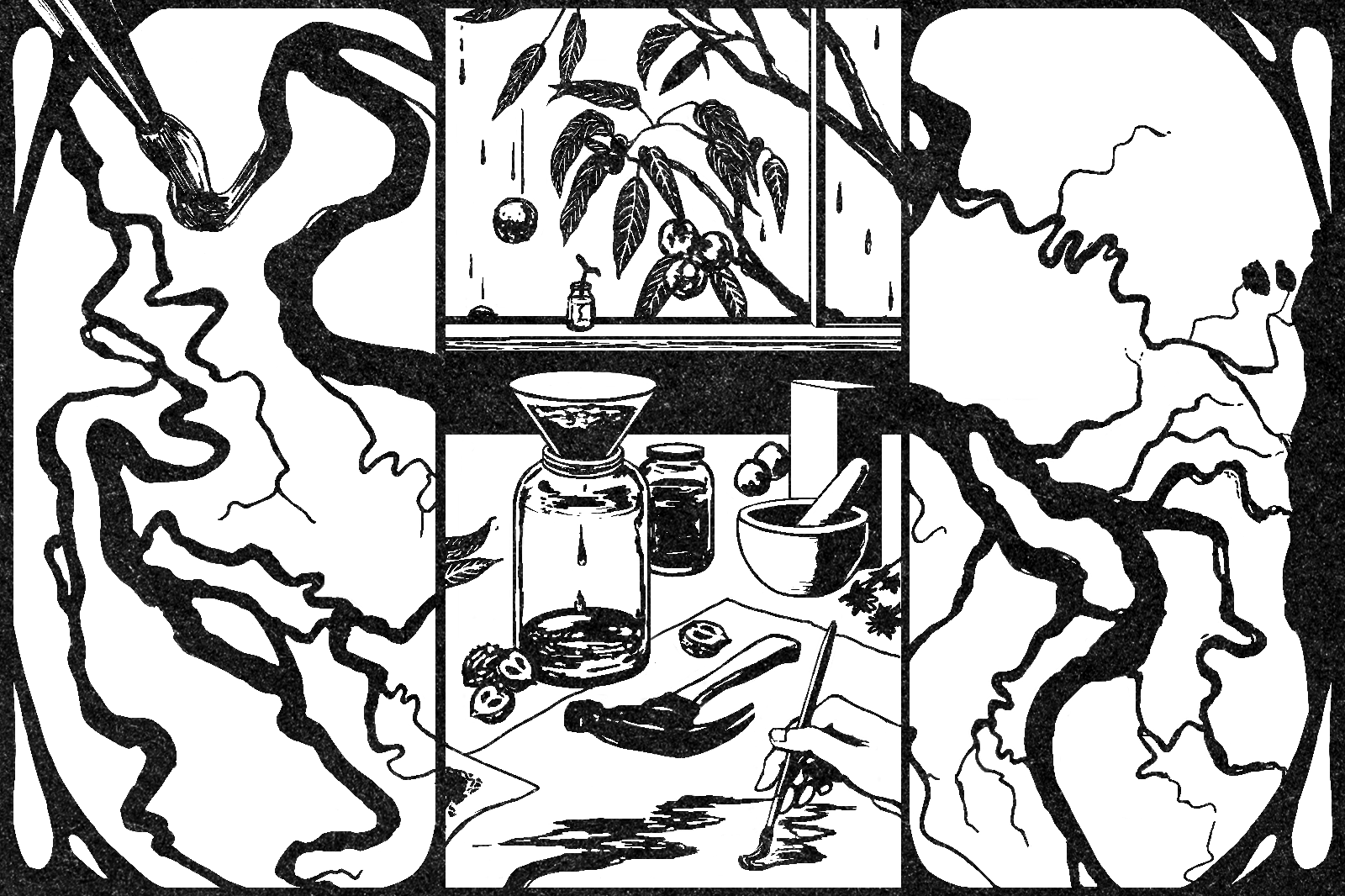

In the category of visual art, First Place was awarded to Dawn Edwards for her felt piece, “Our House.” Second to Vicki Nelson for her painting, “Chaco Canyon.” Third to Karen French for her sculpture, “I Will Carry You.” Honorable mentions were awarded to Shannon Dion for a quilted work “Perseverance,” Cathy Germay for her painting, “The Things We Bury,” and Susan Teague for her drawing “Rooted in Nature.”

Poetry winners were Janice Zerfas, “FYI” (see Zerfas’ poem below); Phillip Sterling, “Untamed Things”; and Elizabeth Kerlikowske, “Those Who Stay”. Honorable Mentions were Penelope Campbell, “Decorating the Tree”; Gail Martin, “Pond”; Christine Parks, “Stalking the Holy”; and Nancy Nott, “Worms and Dandelions.”

Artist Shannon Dion, an honorable mention winner, credits the art festival with giving her confidence when she first submitted her work in 2021. “I have submitted every year since,” she says. “That first year, I marked my fiber piece NFS — not for sale — because I was sure that no one would want it. But then someone did want it, and it sold. This year, I submitted two pieces, and one has already sold. My background is Jewish, and the Hebrew belief is that we must work and guard the earth, so I love that we do this in this festival.”

Artist and guests

Cathy Germay, another honorable mention winner this year and a Grand Prize winner in a previous year, has participated every single year of the festival but one. “My painting this year — “The Things We Bury” — was based on a flowerbed I made a few years ago when we moved into a new house. As I dug up the soil, I kept digging up pieces of trash. We bury stuff so that we don’t have to see it or think about it. It’s ridiculous that as a society, we aren’t doing more about climate change. It is a huge problem.”

“We are on the brink,” says Jim McKim, five-year director of the Beim Foundation. “We must act quickly and decisively to make change — and not just us, but the entire globe. As Carl Sagan said, the earth is our lifeboat. We must take better care of it.”

As the opening day for the art festival concluded, music soothed the awakened spirit. A trio of Celtic musicians, Selkie, tuned up to gather attendees around the altar to listen. Selkie members Jim Spalink, Michele Venegas, and Cara Lieurance performed on flute, fiddle, bouzouki, banjo, guitar, and accordion.

“Westminster Presbyterian Church is an art-friendly, music-friendly place,” Lieurance, who is also a host and producer at WMUK 102.1 FM, says. “I’ve seen the Duggins use the space as a public concert hall for local performers like Joel Mabus, Meredith Arwady — and both times Selkie has played for the art festival, it has been so memorable for the warm welcome and appreciation we’ve received.”

Recent studies in neuropsychology show us that these systems — reason and emotion — are inseparable from one another. Arts — visual, literary, and musical — can move us to make changes when little else does. While Western culture tends to emphasize reason over emotion, both must be engaged if there is to be hope in reversing the damage done to our lifeboat, the Earth.

Editor’s Note: Below is this year’s First Place poem by Janice Zerfas.

FYI

The government wants your dead butterflies as the numbers are declining,

so I read in Nature Conservancy, a one inch ad between

the symptoms of climate change,

and the too frequent occurrence of marine cold spells. A memorial of Lepidoptera

artifacts, sphinx, spanning or skipper as well as boll, corn, or tomato fruit worm.

I would like to know why butterflies count more than reptiles,

if a grass coddling moth more necessary than a plain bellied or a brown water snake.

What makes one species more worthy than another? Beauty, prettier names, coloration?

Locution? Sonics?

If you will follow my attempt at logic, think of the harmless snake encounters, not venomous,

walking along the Paw Paw riverbank; and how the common garter snake with its long yellow-

orange line ribboning brown-black skin hugged itself in the sun.

How it circled into a coiled braid. Believe me, I share with you a phobia of wolf spiders,

mice, and Florida cockroaches.

Who needs Buddha when observing a garter snake sunning, peaceful, calm.

So accepting of its self, its condition. Tempted,

but I did not press it with my garden hoe.

So much bliss in one’s body, doing nothing, unlike cabbage, yucca, and foresters. Skittery.

And do not get me going about tent moth caterpillars with their white-webbed glaciers

ruining fruit trees.

And how on earth do we send in our monarch travesties, bubble-wrapped

black-lettered with the location and date of its finding, as if info saved for a headstone.

And how do I tell my loved ones when they come home from school, what I did that day?

Oh, I gathered dead insects I found by the roadside, a half-wing from a swallowtail,

a ragged spring azure, blue or metalmark, and I stuck each eye spot in a baggie,

remembering the mile marker.

I remember counting the eyespots as if breath intake, and what it felt like to have none,

recalling the last moments. Such a send-off when there is no death rattle!

I tell you: it is the snakes coiled in the river flanking branches nearby coiled as if pottery,

yellow brown bowls sandbagging in the trees I did not expect to find—to nearly walk into,

eye to eye. Lanterns in the daytime! Re-heated pretzels!

A bowl that made and unmade itself! Holding itself, and then letting go.

Unlike the rigid morphos, luna, flannel moths—unable to bend their wings, adapt, and grow.

I plan to save the one that shed its skin for me.