Green between the tracks: An Urban Nature Park

Turning brownfield to green space is the point behind the Urban Nature Park now being created in downtown Kalamazoo.

In the minds of the leadership at Kalamazoo Nature Center, there is no wrong side of the tracks. There’s just the green side.

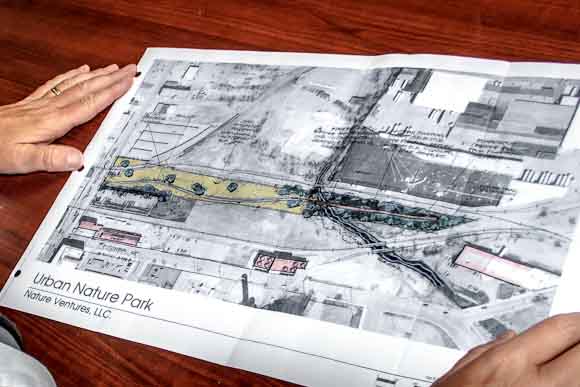

Freight trains once moved across railroad tracks through the four-acre parcel in downtown Kalamazoo where now the beginnings of an urban nature park is taking root. The parcel was once a train yard, later a coal dump. Along Portage Creek at East Michigan Avenue and Pitcher Street, adjacent to the Arcus Depot and across from Food Dance Café, the parcel of land still sports tall weeds and patches of bare dirt, but to the knowing eye, great changes are evident.

An urban nature park is a natural space found in the city, designed to provide green space to urban residents. Traditionally, this kind of green space is found in rural conservation spaces.

The idea for the Urban Nature Park project, says Sarah Reding, vice president for conservation stewardship at Kalamazoo Nature Center (KNC), began with William Rose, president and CEO at KNC.

“The idea came about sometime in 2005, from Bill and other colleagues,” says Reding. “Bill wanted to provide green space for the inner city. Nature is, after all, for people everywhere. This particular parcel had long been an industrial space, a railroad yard.”

The area qualified for brownfield development. Brownfield, Reding explains, refers to an area that has been contaminated.

“People often think of brownfield development as cleaning up an area and then putting a new building on it,” says Reding. “But in this case, we wanted to create green space, and we wanted to help revitalize the Portage Creek and Kalamazoo River areas. I’ve so often heard people tell me that they haven’t thought about the rivers in this area. Our rivers have so long been thought of as contaminated, unusable, and people have almost forgotten that they are there.”

Working with nonprofits as well as for-profits, KNC created a master plan to restore the brownfield site and show the positive effects an urban nature park can have on surrounding property values, urban redevelopment, and quality of life. The railroad agreed to lease the land for the project.

“It’s a movement around the country, not just here,” says Reding. “We are starting to realize—and research backs this up—that nature is good for us, that we need green spaces. Even 10 minutes outside has been shown to calm people. Hospitals are incorporating nature into the healing process; research shows nature helps people heal faster. Kids do better in life when they have access to green space. Intellectually, emotionally, as well as physically.”

Bill Rose approached Jon Stryker of the Arcus Foundation to talk about his idea of an urban nature park, and the Foundation provided initial funding with a grant in 2005. Nature Ventures, LLC, also run by Bill Rose, was formed as a sister company to KNC to oversee the project. Mostly private funders have kept the project funded.

The first two phases of the four-phase project, Reding says, involved intensive clean-up. Countless volunteers dug in alongside KNC employees.

“There was a lot of industrial material to remove,” she says. “Cement pieces, metal, railroad ties, telephone poles. Much of it was done by hand, but much of it also by machinery, taking away all the garbage. We tested and removed the soil, graded it, then put in topsoil.”

The next phase includes planting native plants, shrubs and trees in the wetland area of the project. Plants have been selected based on historical records, as well as soil types, and as optimal for native species of birds and butterflies.

“Our field director, Ryan Koziatek, has spent the last year doing the planting,” adds Reding. Invasive plants such as Queen Anne’s Lace, Reed Canary Grass, Nightshade, Mullein, Common Buckthorn and Myrtle first have had to be removed. Nitrogen-regenerating native plants were chosen for replanting.

Reding says they worked along the Environmental Protection Agency, or EPA, to plant once the agency had cleaned PCB contamination from Portage Creek. “They were very helpful. It was a great relationship, working with the EPA.”

Complete replanting of the site was the only appropriate option, reports Bill Rose. “The EPA was very excited for the opportunity to be a part of this kind of project,” says Rose. “They were very accommodating and worked with Nature Ventures to simplify wetlands restoration and replanting.”

Another aspect of the current phase is the restoring of a railroad bridge and building a 200-foot boardwalk. Wetlands mitigation will involve filling in one wetlands area, but then reconstructing it in another area.

“The aim of restoring native habitat is that we hope to entice indigenous species such as the American kestrel, some of which have vacated the area, to return,” says Rose.

Some of the native plants to be planted throughout the site include Black-Eyed Susan, Purple Coneflower, Gentian, Spiderwort, among many others.

“We’re putting in a trail over the next year, and we hope to connect it eventually to the Kalamazoo River Valley Trail,” says Reding. “It’s a hope. There are a lot of property owners in between.”

The fourth and final phase, which is ongoing, will be to monitor the site, pull invasive plants that reappear, mow and rake, but to also monitor the site for any signs of vandalism, such as graffiti on the boardwalk, signs, or on the bridge.

“The Urban Nature Park will be a great amenity for the city and people of Kalamazoo for years to come,” says Rose. “Other properties nearby provide potential for future expansion. Along with the Nature Park, the recent founding of the new WMU medical school’s W.E. Upjohn Campus just blocks away promises a near future of revitalization for this area of the city.”

“It’s taken a long time to go from an idea to developing goals, working with the EPA, all the steps of working with all our partners,” acknowledges Reding. But it’s worth it, she says. “We’re losing an entire generation of kids that never play outdoors. All kids need green space to play within a five-minute walk. The Urban Nature Park will give city kids a place to go. It’s part of Kalamazoo Nature Center’s No Child Left Inside initiative.”

It might take parents at first giving their kids a nudge to step away from the televisions and computer screens, Reding says. Then, she says, Nature takes over.

Zinta Aistars is creative director for Z Word, LLC, and correspondent for WMUK 102.1 FM Arts and More program. She lives on a farm in Hopkins.

Photos by Susan Andress.