Former Albion wrestling standout comes out of the closet and wrestles with the truth

“I had a private life and a public life and I decided who knew what. Now that the book is out I have a recorded legacy of my authentic truth.”

Editor’s note: This story is part of Southwest Michigan Second Wave’s On the Ground Battle Creek series.

Robert Shegog had to earn the opportunities he had to become a teacher and wrestling coach and he wasn’t going to let being a gay Black man get in the way.

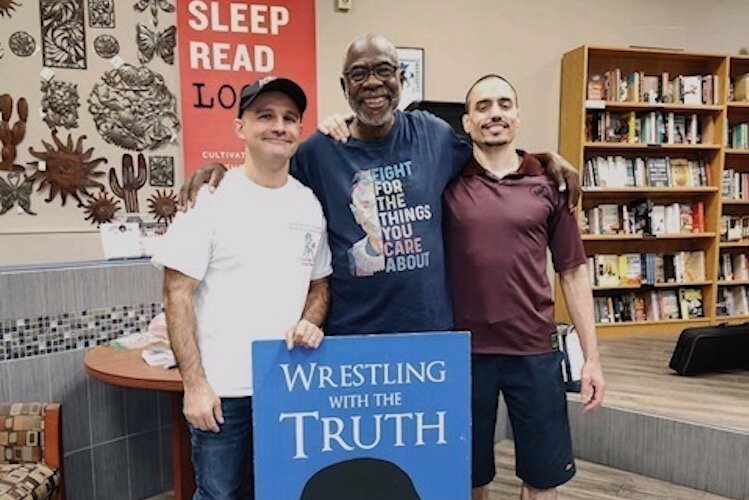

So, he decided during his growing-up years in Albion to keep his homosexuality a secret from everyone, including his family. One month shy of his 73rd birthday, he’s coming back to Albion. On Sunday, Oct. 6 he will give a talk at 3 p.m. at Stirling Books & Brew about a book he co-wrote with a former student which addresses his life as a closeted gay man.

Titled “Wrestling with the Truth,” the book offers a deep dive into what led him to both stay in the closet and eventually come out with support and more than a little encouragement from Dr. Nicholaos Kehagias, an Anesthesiologist with a medical group in Chandler, Ariz. Shegog was his teacher and wrestling coach at North High School in Phoenix, Ariz.

Kehagias says it wasn’t until after he graduated from North in 2000 that he learned that his coach and teacher was gay, although there were clues along the way.

“

There were little things like whenever we called him we would hear a message on his answering machine in the voice of his partner Robert,” Kehagias says. “As high school kids we were trying to figure out what that meant and sometimes being immature kids, we would show up for practice and say, ‘Who’s Robert? Is he your gay lover?’ Coach would tell us his wife was in San Diego and he would sometimes go off to visit her. I didn’t want to dive into it because I had a lot of respect for the guy.”

On a personal level, Shegog didn’t have a lot of respect for himself about the way he chose to manage the three committed relationships he’s had. Each of his partners passed away and he wasn’t able to acknowledge the gravity of these losses publicly until now.

“My regret is that I’ve lived as long as I have because I’ve lost so many friends. I have survivor’s guilt and when I see people who have been married for 40 or 50 years. I’m so envious of them for the comfort with having a partner who understands them so well that they don’t need to talk a lot.”

A diagnosis that changed his life

In 1986 while he was with Russell, who he considers his first real partner, Shegog found out he was HIV positive. Russell had already been diagnosed with HIV and Shegog’s physician told him that if his partner had it, Russell had it and a test confirmed it. At that time, people with HIV were given 12 to 18 months to live. His diagnosis came five years before basketball great Magic Johnson would disclose his own HIV diagnosis.

Russell died in 1988.

A combination of old and new medications has kept Shegog alive and his HIV undetectable for 24 years, something for which he expresses both boundless gratitude and remorse. Though he is a self-described optimist who tends to always look for the good in others, he says the subterfuge he engaged in to keep the door closed on his intimate relationships will always be with him.

“I never allowed my partners to ever come to wrestling meets,” Shegog says.

While teaching and coaching the Flint Beecher High School Wrestling Team, his partner at the time was a white male.

“Some white guy coming to watch wrestling would have been noticed because it was a predominantly Black-attended school,” he says.

Unbeknownst to him, that partner had been donating money to the team. His mother shared this with him after his partner died.

“I regret that,” he says of being unaware of these donations.

He never went shopping with his partners and before going anywhere public, he would take off his wedding ring and put it in his car ashtray. He avoided attending any social events with fellow teachers and if he did have to be somewhere that required him to bring a woman along, one of his lesbian friends would accompany him.

But, some of his colleagues at North High School, the school he retired from in 2006, saw through the carefully-tended web of secrecy and told him they knew he was gay.

“They gave me all these reasons not to come out,” he says.

During an earlier teaching job at Hartland High School 20 miles north of Ann Arbor, a teacher there, not knowing that he was gay, told him he should get married so that people wouldn’t think he was gay.

This was a tactic used by Hollywood film studios as far back as the 1920s, according to an article on the History Channel website.

“Queerness could be appreciated on stage, but in the everyday lives of major stars it was often hidden in sham unions known as ‘lavender marriages,'” said Stephen Tropiano, professor of Screen Studies at Ithaca College and author of The Prime Time Closet: A History of Gays and Lesbians on TV.

“These marriages were arranged by Hollywood studios between one or more gay, lesbian, or bisexual people to hide their sexual orientation from the public. They date back to the early 20th century and carried on past the gay liberation movement of the 1960s.”

Shegog says he was unaware of the Hollywood solution to being gay until he was older, but he was very conscious early on of the outward-facing life he’d need to build to teach, coach, and survive.

Wrestling his way to success

Shegog is the youngest of four siblings raised by a single mother who moved the family from Buffalo, NY, to Albion to escape an abusive husband.

A single woman with children in a small town at that time invited gossip and remarks like, “Ladies you better lock your husbands up before she gets her hooks into him,” Shegog says. “As a result, my mother was very strict and a hard worker. She was a big influence on my life.”

He began wrestling in 7th grade after he and three fellow students were selected by their Physical Education teacher to practice with the Albion High School Wrestling Team. The three would begin competing when they began their freshman year there.

Shegog excelled in the classroom and on the wrestling mat competing in and winning matches at the local and state level. Wrestling scouts recognized his talent and in a conversation with them, he was asked what his GPA (Grade Point Average) was. He didn’t have a chance to respond because his coach stopped him, citing NCAA rules, but he was able to connect the dots between a solid GPA and scholarship opportunities.

“The light went on that I could get a scholarship and go to college doing something that I love. I made sure my GPA was up there,” he says.

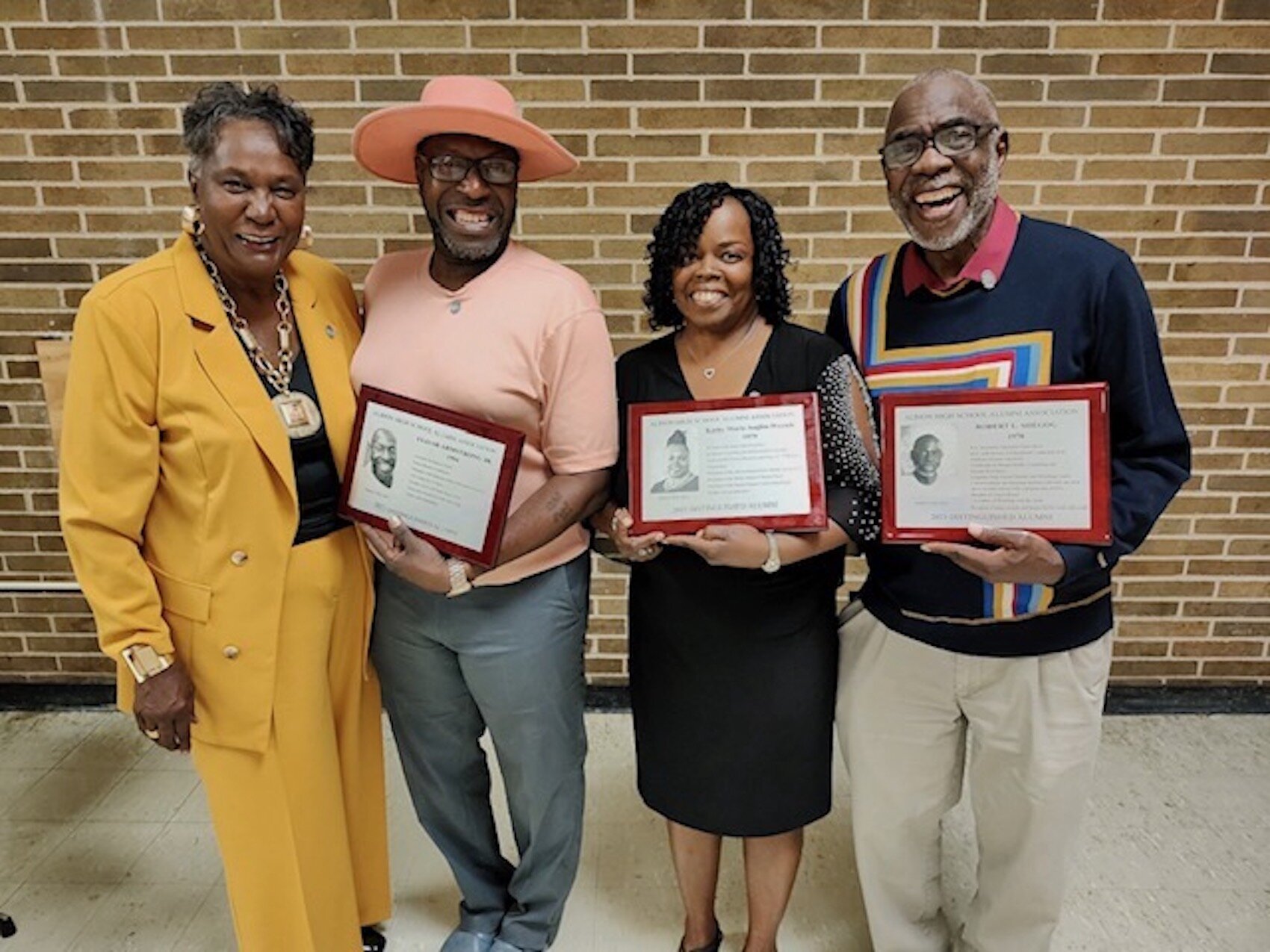

He was offered a full ride to attend the University of Olivet (formerly Olivet College) where he was a member of the Wrestling Team all four years. In 1992 he was inducted into Olivet’s Athletic Hall of Fame. A statement on the school’s website cites his numerous accomplishments, including his “outstanding personal record at Olivet -— 61 wins, 18 losses and 4 ties.”

On Saturday, he will join with teammates from the 1974 Wrestling Team to be honored at Olivet for their undefeated season.

The years after college

Wrestling may have paid for his college education, but it was his degree that paid for his future. He majored in Secondary Education, Social Studies, and History with a minor in Physical Education. After graduating with a Bachelor’s degree in 1974, his first teaching and coaching job was with Hartland where he taught and coached track, cross country, and wrestling.

He says he was hired because he was Black.

“The school took the kids on a field trip to Lansing. While they were there, some of them were using the “N” word. Teachers reported this to the principal who said the best way to address this was to hire a Black teacher,” Shegog says. “They recruited me from Olivet. I was there for two years and my job was going to be eliminated because a millage failed. I was really honored that a group of parents got together and offered Hartland money to pay my salary.”

The school couldn’t accept the money to save his job because of seniority issues. He then taught and coached wrestling at schools in Flint and Jackson before an abusive relationship with a man he was involved with off and on for five years led to his decision to leave Michigan to find work out West. He spent some time in Los Angeles where he worked as a teacher’s aide, a waiter, and in construction. He met Russell, who was living in Arizona, at a district meeting for a church they both attended, and 21 days later he moved to Phoenix where he took a teaching and coaching job with the Phoenix Union School District and lived with Russell.

He taught and coached at high schools including South Mountain, Trevor Brown, and North.

Former student encourages him to tell his story

Kehagias remembers Shegog doing everything he could for his student wrestlers including cutting up oranges for them to eat, buying their wrestling shoes and student insurance ($19 at the time), giving them rides home after practice, organizing parents to provide rides and asking his fellow teachers to recruit students in their classes.

“He would do anything to prioritize the program,” Kehagias says. “If we ever had an issue in the classroom, we’d let him know first.”

As the graduation of his students approached, Shegog did exit interviews with his wrestlers.

“I would ask them what they were going to do after high school and what they learned in wrestling would help them,” Shegog says. “North was an inner-city school with a lot of Black and Hispanic students and gangs. Many of the students were not living with their biological parents.”

His involvement with his wrestlers continued long after they graduated and he continues to hear from many of them.

Kehagias is an example of that. He had originally planned to attend college in Arizona. Shegog convinced him to attend the University of Chicago where he received a full scholarship and was on the wrestling team and was also in the Top Six in the NCAA Division 3. After earning a Bachelor’s degree in Biology in 2004, he went back to Arizona and graduated in 2010 with a medical degree from the University of Arizona in Tuscon.

Shegog came out to Kehagias in 2005, one year after his high school graduation.

“When I learned his story I was inspired. It was amazing what he went through for his job and he was always at risk because he was gay and had HIV. The fact that he was able to navigate this inspires me and thousands of other students,” Kehagias says. “He had such a big impact in the shadow of this and also being Black everything he had to go through because of that. It just added another layer of challenges that would leave most people angry at the world.”

Kehagias first approached his coach about telling his story 15 years ago. At the time, Shegog said he wasn’t sure he wanted to open up about it. “Once COVID hit, I thought this might be the best time to do it. I told him I’d write it for him.”

“Nick called me to say, now’s the time to start writing. The next day he shows up at my house and stays for four days and he interviewed and recorded me from 8 to 4 every day,” says Shegog/

The two worked with each other through a shared Google document. The book was completed in 2020 and published in 2022. A portion of the proceeds for each book sold goes into a scholarship established by Shegog at the Phoenix Union School District. The scholarship is awarded to a North High wrestler looking to pursue secondary education.

Among the book’s biggest takeaways for Kehagias is the life Shegog couldn’t acknowledge or celebrate publicly.

“He basically had to live a lie so that we could benefit,” Kehagias says of the student wrestlers like him. “It was an extremely selfless act.”

While Shegog is grateful for the support from his former students, he wishes that he’d been able to always be his authentic self.

“I had a private life and a public life and I decided who knew what,” he says. “Now that the book is out I have a recorded legacy of my authentic truth.”