A bike counter registered 2,500 bikes on the lanes per month, which is around 2% of the average daily traffic, “standard per-national average of ridership in the U.S.” — Dustin Black, ModeShift

Editor’s note: This story is part of Southwest Michigan Second Wave’s On the Ground Kalamazoo series.

Transportation modes in Kalamazoo are shifting — slowly but surely.

Both the City of Kalamazoo and local transportation-alternatives groups are pushing for streets that allow multiple modes of travel — bike, foot, bus, and car.

In keeping with the request of residents during the master plan process, the City is putting emphasis on reconfiguring major streets so drivers must keep at or below the speed limits that’ve long been set at 25-35 mph in most downtown areas.

A big part of this reconfiguration is bike lanes along Westnedge and Park. This gives some hope to city bikers looking to switch from gas-burning vehicles to pedals for everyday travel.

In the months after the mid-summer arrival of the lanes, the response from all road users has been mixed on the Park and Westnedge changes.

A two-way protected lane on Lovell St. yielded a more positive result. The September-October pilot project, a bike lane protected by a “bike wave,” had an “overwhelmingly positive” response, ModeShift’s Dustin Black says their survey shows.

Utilitarian biking family

Some people have realized that it’s possible to live nearly-car free, even in Kalamazoo, thanks to bicycles. These riders are not so much “cyclists” as they are “grocery-getters” and “kid-toters.”

“Yes, we are the biking family!” Alexandra Filonyuk declares.

Since Filonyuk and Wilson Xu purchased large cargo e-bikes, bikes have become their main means of transportation.

“Our youngest kiddo, still a baby, loves the bike rides, but fights the car,” she says. “We send our daughter to school on a bike, go to work, to downtown, grocery shopping, go out to eat, go to parks and playgrounds and birthday parties on a bike. I guess this makes us regular bicycle commuters.”

Xu says they have four e-bikes and four “normal bikes.” The pedal assist and speed of e-bikes help them go further and carry more. He notes that his eight-mile ride by e-bike to work takes just a few minutes longer than driving.

The couple also has an electric car and a regular gas-burner. Why not use them?

“I grew up on the back of a bicycle in the late ’80s to early ’90s in China, and I hope to raise my kids to prioritize bicycles over cars when they think about transportation,” Xu says.

“My wife and I both lived in Asia in our 20s. For six years we didn’t have a car, and used public transportation and bikes to get around,” he says.

“After we moved back to the U.S. we were not used to the mental stress of driving and car ownership…. We just decided we need to reduce driving as much as possible and substitute driving with biking…. We still drive if the distance is more than 12 miles or if the journey seems too dangerous to bike — like Sprinkle Road. Most of our car journeys are between 20 to 100 miles, anything more, we try to take the train.”

Wheel-runners and wheel-walkers

One of ModeShift’s messages is, not everyone on a bike is a “cyclist.” Witness Alexandra Filonyuk and Wilson Xu.

ModeShift has been active in Kalamazoo since December 2021. Dustin Black says of his group. ModeShift is “a small community collective that works to champion walking, biking, and taking transit in our community, and we think we can build a more cohesive community through that,” he says.

“We want to celebrate the things that are already happening, more so than advocating for additional change. There are other changes we’d like to see, but I think if you champion the wins that are already happening in our community, those tend to develop more frequently and naturally.”

Bike Friendly Kalamazoo recently presented ModeShift with their Civic Leadership Award in October, for their “Re:Cycle” bike event in May, and their promotion of “the use of bicycles as everyday transportation, and for bicycling infrastructure that can accommodate riders of all ages and abilities,” the BFK press release states.

Black’s profession as a transportation engineer has led him to believe that “getting people out of cars” is important.

One point he’d like to get out into the general public is there are different types of riders and they bike for different reasons.

There are two terms used in the Netherlands for bike riders, he says. Translated from Dutch, one is “wheel-runner,” the sporty, fast cyclist. The other is “wheel-walker… which might be a mom and her kids, might be someone going to get groceries,” he says.

“In North America, we really don’t make that distinction. We call everyone a cyclist. My wife rides a bike almost every day, and she would be offended if she were to be called a cyclist.”

Some people want to push themselves to the limit on a bike. And some people just want to get groceries, save on gas, be a bit more active, and leave the car at home, he points out.

The latter are who “we’ll call the transportation cyclists, or the utilitarian cyclists,” he says. They go for a more upright, comfortable bike, “they don’t have the spandex on, sometimes they don’t have helmets… and they’re doing zigzag trips. They’re going to the store to get this, they’re going over here to drop off the dry cleaning, over here to pick up their child from daycare.”

Black says that studies show most car trips are short. Maybe short enough for most people to pedal.

A March 2022 study from the Bureau of Transportation Statistics shows that in the U.S. 52% of all trips (including driving, rail, transit and air) were less than three miles, and 28% were less than one mile.

All that’s needed is the infrastructure that people feel safe biking on, and that works as a travel network, not as disconnected lanes. “Just open up new avenues for people who don’t want to drive one mile or half of a mile for whatever errand they’re doing,” he says.

This will benefit drivers, too, he says. “If we could get those people out of cars and onto other modes, that’s taking traffic away. That’s easing congestion.”

The famous “bike utopia,” the Netherlands, Black points out, “has the highest driver satisfaction in the entire world, five years in a row.” There, utilitarian biking is common, “but it’s also the best place to drive.” That’s because “people have choices, and that’s what freedom is all about,” he says.

Bike Wave

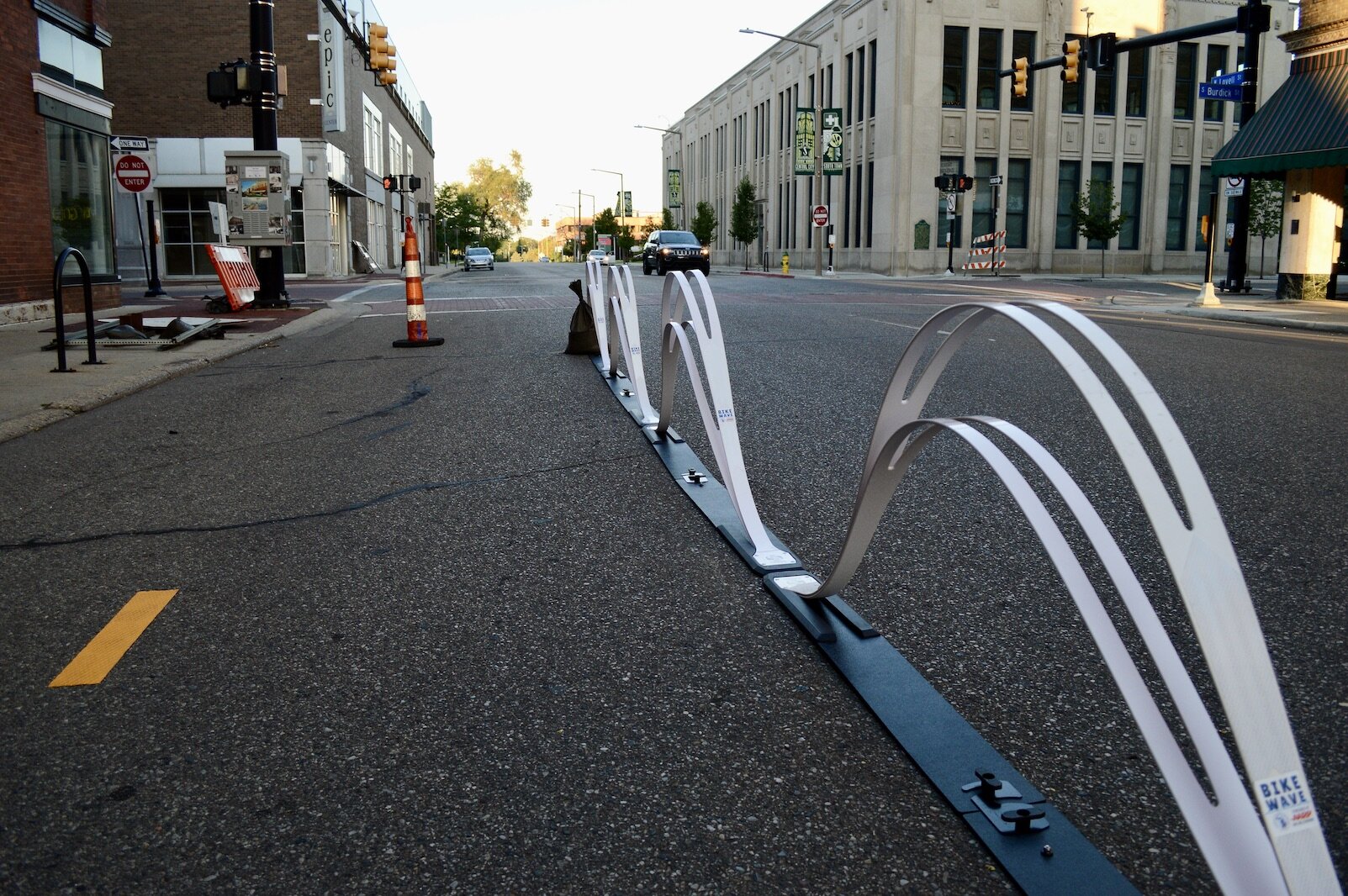

ModeShift partnered with the Vine Neighborhood Association, the city, League of Michigan Bicyclists and the AARP for its Bike Wave pilot along Lovell late summer-early fall.

The two-way bike lane featured wavy flexible delineators between traffic and bike lanes.

Black says that a survey on the Bike Wave had positive responses from drivers and bikers. The barrier provides “clarity, and everyone knows they’re where they need to be. (To) have a good idea where to expect the other person, that’s where safety really goes up.”

The difference between riders’ and drivers’ opinions in the survey was that drivers “liked flexible post delineators and painted buffers more, and the people who biked actually liked the bike wave itself…. but they also liked the idea of having plantings and greenery as a buffer.” In other words, riders want solid barriers between them and cars.

A bike counter registered 2,500 bikes on the lanes per month, which is around 2% of the average daily traffic, “standard per-national average of ridership in the U.S.” Black says.

“So the ridership is there. Having that data is important because people go, ‘Oh, I’ve never seen a bike on there!’ Well, open your eyes. They’re there. Several per hour,” he says.

Bikers still not feeling safe

It took some time to get to where they could use their bikes more than their cars in Kalamazoo, Filonyuk and Xu say.

Filonyuk says getting out of the car and onto a bike “definitely includes some route planning, exploring the neighborhood streets. I try to avoid the major car-heavy routes.”

She continues, “The more you ride, the more comfortable you feel. As a female rider, and a Mom with kids, a very careful rider… I in general get lots of emotions from other road users. I get lots of smiles and hand waving, many questions. Many times the drivers slow down, lower their window and ask me, where I got ‘THAT’ (the cargo bike), or if I need help and if I will have to walk the bike uphill.”

Some drivers go out of their way to be aggressively, dangerously nasty to her, she says. “Road rage is a real thing, though — and I encountered some very angry drivers getting into a bike lane to block me from moving forward, and trying to drive me off the road.”

“I do like that the city is working on developing the bike infrastructure and providing the citizens a chance to choose their mode of transportation,” she says.

But her opinion on the new Westnedge and Park bike lanes turned sour from one ride. “It was a very scary experience. I encountered angry drivers trying to push me off the road, and my bike lane ended abruptly. (Since the lanes are on the left side of the road) to get home I needed to turn right and cross multiple lanes with cars. Luckily, it was Sunday and the road was not busy. No way I would take Westnedge Road during a weekday.”

She’d like to see barriers placed between car and bike lanes. “Also, I would like to see a shift toward developing a connected bike network, rather than a series of disconnected street segments popping around town here and there.”

Xu says, “Prior to becoming a parent I actually thought the roads in Kalamazoo were decently comfortable for bikers. Now that when I ride with my kids I don’t feel as comfortable on most shared roads.” He’d like to see bike lanes protected, plus “more connections between Kalamazoo and Portage.”

Slowing traffic is the city’s first objective

The City is monitoring the new bike lanes on Park and Westnedge, and so far they’ve seen average speeds decrease around three to five miles per hour, and “we do not see any indication of an increase in crashes,” Dennis Randolph, traffic engineer for the City of Kalamazoo, says.

“Since nearly 60 percent of all crashes in the City have speed-related causes, it makes sense that as speeds go down, so will crashes,” he says.

However, “it will be next summer before we can speak with any certainty” about the impact the lanes have had, he adds.

Randolph says, “we must emphasize that while we have placed the bike lanes for bicyclists to use, our first objective is and remains to slow traffic. To slow traffic, we narrowed drive lanes and eliminated excess lanes.”

Since 1965, when the city turned streets over to MDOT control and they were turned into wide, one-way, multi-lane throughways, “conditions have encouraged speeding along streets such as Park, Westnedge, Michigan, and Kalamazoo. Therefore, it will take some time for drivers to understand that they all need to obey the posted speed limits. We hope to get drivers to obey speed laws without excessive enforcement efforts by using techniques such as lane narrowing and lane reductions, which are proven methods to slow traffic,” he says.

“Unfortunately, the fact is that both Park and Westnedge have more lanes than are needed to carry traffic safely and efficiently. As a result of too many lanes, traffic travels too fast. Fifty to 60% of the traffic on Park and Westnedge travel over the posted, legal speed limit. This excessive speed results in crashes and excessive ‘dodging and weaving’ by some drivers, which leads to more crashes.”

Since the beginning of the project, the city added some flexible post bollards, but recently removed others. Green paint has been added to delineate “bike boxes” — spaces where bikes can wait to cross at intersections, and green “cat tracks” through intersections, that remind drivers and bikers where bikes cross.

Bollards have been removed recently “to facilitate snow removal and leaf pickup,” Randolph says. “We have left bollards at the beginning and end of street sections to make it clear that the lanes are still not for motor vehicle traffic…. We expected some adjustments to be made and, in part, hoped that as drivers got used to the new lane configurations, we could eliminate some traffic control devices.

Randolph adds, “From our observations, it seems that most drivers understand what we are doing and respect the bike lanes.”

But the city has heard from drivers who’ve been angry with being forced to slow to the speed limit. “Many people who have expressed concern with our pilot bike lanes along Park and Westnedge have simultaneously expressed their frustration at slowing down. However, slowing traffic has been our primary objective because most drivers disobey the posted speed limits on our streets, making the streets unsafe and the abutting neighborhoods less livable,” Randolph says.

‘Transitions are messy’

Black feels that more delineators — flexi-posts or something more-solid, are better than “just a white line.”

If drivers can drift over a line into a bike lane, “Who’s going to use it? It’s still going to be the hard-core cyclist or the ones who’re a little more cavalier than your mom and kids, probably,” Black says.

Other Midwest cities — Chicago, Detroit, South Bend, Ann Arbor — have built up their bike infrastructure. Is there something different about Kalamazoo that holds it back?

“I think Kalamazoo’s been a little bit slow in doing it,” he says. Black then points out that Ann Arbor — now a Gold-level Bicycle Friendly Community according to the League of American Bicyclists — once piloted a two-way cycle track. It was successful, so they’re now planning their fourth, “another link in the chain” of a bike transportation network.

Black has criticisms, but he sees Kalamazoo setting the stage for its future in its street plans and recent zoning attitudes.

“Transitions are messy, in general,” he says. “The city of Kalamazoo is really figuring some things out, how it works in a local context. But the endgame, which is where my head is at, the endgame is a transportation system that works better for everybody, not just bicyclists and not just people who walk, but better for everybody, including drivers.”