Black Wall Street Kalamazoo looks to build generational wealth in the African-American community

Nicole R. Triplett founded Black Wall Street Kalamazoo in 2018 to build wealth in the Black community by keeping money circulating longer in the Black community.

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

Editor’s note: This story is part of Southwest Michigan Second Wave’s On the Ground Kalamazoo series.What if Kalamazoo’s African-American community shopped regularly — if not exclusively — at Black-owned stores, ate at Black-owned restaurants, and employed Black-owned roofers, cleaners, electricians, accountants, and doctors?

More of their money would circulate longer in the Black community, allowing more members of that community to benefit from it, build wealth, and prosper, says Nicole R. Triplett, of Kalamazoo.

That would be a means to build wealth, says Triplett, founder of Black Wall Street Kalamazoo. It is also something that other ethnic groups have done over many years while disparities in income levels, education, and access to capital have left many in the African-American community struggling to catch up with others reaching for a piece of the American Dream.

Triplett says failure to keep dollars spent by African-Americans in the community longer makes it difficult for the Black community to build wealth within their families and amass financial resources (homes, property, businesses) that they can pass down to their children — the concept of shared generational wealth.

So she started Black Wall Street Kalamazoo in December of 2018 to get that economic ball rolling. It started with the creation of an online platform that allows Black entrepreneurs to post information about their goods and services. And it allows other members of the community to search for goods and services they want or need. That directory of Black-owned businesses is available on Facebook here.

“If you type in any type of business that you’re looking for, you should be able to locate it and it will be Black-owned,” Triplett says of the directory.

Dr. Benjamin Wilson says there’s a history of Black entrepreneurialism in the United States, evident in any number of all-Black towns that appeared after the abolition of slavery, and almost completely supported by Blacks – who were not welcomed in many White establishments. He mentioned towns that sprung up in Kansas, Colorado, North Dakota and Oklahoma.

“It shows that Black folk have an amazing ability to survive in a hostile environment, constantly fed on a diet of hope, faith, love of their own blackness, and their sense of self-esteem,” says Wilson, who is professor emeritus of the African-American and African Studies program at Western Michigan University.

Now retired from teaching, Wilson has been a consultant on various historical documentaries including the film “Up From the Bottom: The Search for the American Dream.”

Asked if he thinks efforts to nurture more support for Black-owned businesses will be successful in what is now a racially integrated society, he says, yes they can be if the businesses involved match or exceed the level of service, quality, or proficiency that everyone has come to expect from all businesses. That is to say people – Black or White – won’t necessarily support a business just because it’s Black-owned.

“If you’re going to open a business, be accountable,” Wilson says. “… The quality of your service has to be just as good to attract people and continue to attract people.”

“But it’s a slow process,” Wilson says. “because we didn’t have any inherited wealth that our parents might have left us, whether its property or cash.”

“We’re starting from ground zero and building up, ” he says of a majority of African-Americans.

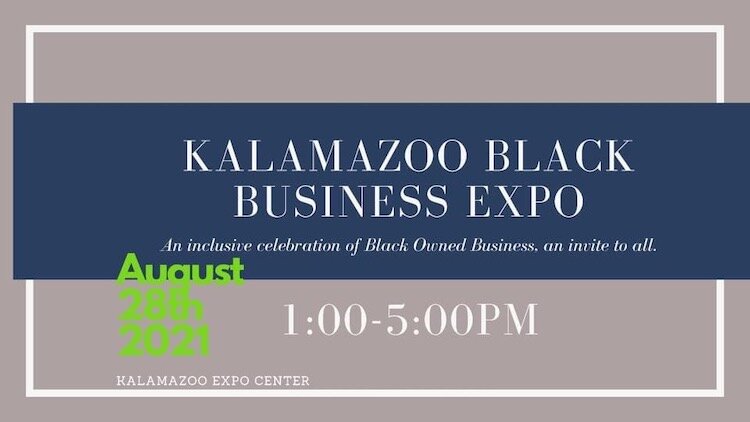

After setting up the directory of Black businesses, Triplett planned and hosted a Black Entrepreneur Boot Camp and a Kalamazoo Black Business Expo in 2019. The expo is an annual sellers’ event held at the Kalamazoo County Expo Center. It has attracted dozens of small Black-owned businesses to sell their wares and network.

The Boot Camp provided training to help people understand the ins and outs of running a business and get more formalized education around whatever their natural talents are. That has included getting organized, maintaining proper paperwork, and running a business professionally.

“What we found is that even if we were to begin to create generational wealth, there was not a lot of financial education,” Triplett says. “There was not a lot of business education. So we would want to make sure the businesses could run correctly so they would be successful.”

In 2020, Black Wall Street Kalamazoo began partnering with Sisters in Business Michigan, a networking and mentoring organization focused on supporting local African-American women. It was started in 2017 by four local women who are siblings — Alisa, Tiffany, Teleshia, and Nicole Parker. They collaborated with Black Wall Street to conduct the Black Entrepreneur Training Academy, a five-month training course that started in April of 2021 to equip, support, and provide resources for African-Americans who want to start a business or grow the one they already have. Following the course, the academy includes another seven months of mentoring.

The cohort-based virtual-training program has a curriculum facilitated by experts and delivered in pre-recorded videos and live virtual sessions. It includes developing a business mindset, understanding business structure, and development, managing business finances, developing a business plan, marketing, and learning to pitch a business to potential customers and investors. The BETA academy graduated 10 business people in its first outing and is looking to accommodate the same number again this year.

Black Wall Street Kalamazoo is a 501c3 nonprofit organization that gets about 85 percent of its funding from foundations and financial institutions. It also derives income from a few rental properties that it has acquired with the help of contributions it has received, as well as from selling merchandise during events, and from participant fees from its business expo and boot camp.

Triplett derives no pay for her work with the organization but hopes to get grant funding this year to hire staff and fund her leadership role. Triplett says people sometimes ask why the organization favors Black instructors for the BETA Academy and they ask why can’t businesses that are not Black-owned be included in the online directory.

“This is a space created for those who are intentionally wanting to support underserved or unprivileged business owners and they are not able to readily identify those businesses,” Triplett says. “So in order to make them easily accessible, we like to highlight them and put them into one space.”

Triplett says Kalamazoo needs everyone to succeed for the overall community to succeed. But when people want to support a diversity of businesses, it’s not very easy to find minority-owned businesses.

“If you’re intentional about that and that is one of your passions, then you wouldn’t know where to start,” she says. “You wouldn’t know where to go. It’s not as easy as walking down a street and being able to identify it.”

Economist Timothy Bartik says, “Urging people to buy from minority entrepreneurs can be a crucial help to those businesses just as it can be for any small business. But I think you have to have more than that to have long-run sustainability. You need to get some capital. You need to figure out how to reach a variety of markets, not just your own neighborhood.”

Bartik, who is a senior economist with the W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, says he thinks there is a path to prosperity by helping people become more aware of goods and services that are available here, which the directory of Black businesses helps to do. And he says, “There is some logic around the notion that encouraging more purchases at locally owned firms can, on the margin, have higher multipliers than purchases at non-locally owned firms.”

That is because locally owned firms tend to use locally owned suppliers, and since the owners of those businesses are local, more of their personal spending will be done at local businesses, he says.

But if you want to grow your economy, he says, you need to have firms that sell to outsiders and you will need to buy from outsiders.

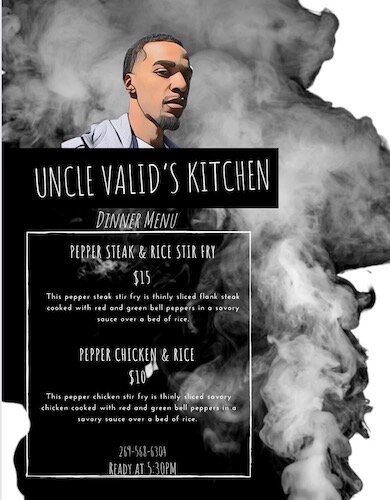

“If you open up a restaurant, you want to encourage local people to buy there,” Bartik says, “But you also want to encourage tourists coming to town. And hopefully, that brings new dollars into the community. If you want to expand Black-owned businesses, they certainly should try to encourage people within the Black community, or people interested in helping to support the Black community, to buy from these businesses. But you’re also going to need to figure out how to sell your goods and services to people who have no particular interest in that and just are trying to buy whatever they find to be the right combination of quality and price.”

Triplett says there has been a significant increase in the number of African-American business start-ups in Kalamazoo over the last few years. And she says her organization has helped more Black people get funding for their businesses during the last few years than there has been in the previous 17 years. “So we’re already making great strides,” she says.

But she says, “We’d like to see more storefronts or Black-owned businesses that are scaling — scaling meaning they are reaching over $100,000 a year in sales and that they are having longevity of over five years. We would like to see people being able to invest in real estate here.”

Triplett says her organization and Sisters in Business are preparing to launch the second cohort of BETA in April and then do a virtual self-paced version of the course. That self-paced course will allow people to pay to access just the video content of the program.

Triplett, 43, is a limited license psychologist who has worked as a family counselor for the last 16 years. A mother with one adult daughter, she has operated her own private practice for the last 12 years. She relocated to Kalamazoo from Indiana at age 9 and is a 1996 graduate of Loy Norrix High School. She has undergraduate and graduate degrees from Western Michigan University. And she is the first Black woman to become a licensed winemaker in the State of Michigan.

In March of 2021, Triplett opened Twine Urban Winery, a wine tasting room at 1319 Portage St. It’s also a maker and seller of wines, featuring The Roche’ Collection, premium wine made from grapes grown in Michigan. Triplett says she began in winemaking by making a wine she’d like to drink, using space she converted at her home. She began sharing the wine varieties she made with friends and things grew from there. Her Roche’ Collection is now sold in Meijer stores and at various local retailers.

Of African-Americans successfully supporting one another to start more businesses and build generational wealth, Wilson says, “It’s doable. It would be more than doable if Blacks had seed money. If we had inherited wealth, it would be more than doable.”

Among communities where concentrating Black capital has been successful and where it is being pursued again, Wilson mentioned Idlewild, the inland lake resort area in rural Lake County. It was founded in 1912 as a vacation spot for Blacks when Jim Crow laws barred them from White vacation spots, restaurants, and most hotels. At its peak in the late 1940s and 50s, it had hundreds of cottages that attracted tens of thousands of vacationers. Many of its facilities languished after the Civil Rights Act of 1964 prohibited segregation and Blacks were able to vacation in other locations. But Wilson says the area is being revitalized.

“It’s attracting a lot of young African-American people who don’t want to see the resort disappear because of its historical significance,” he says. “…We’re talking about a lot of young people basically from the Detroit area doing things to revitalize the resort. A lot of the old places have been rehabilitated. A lot of newcomers are moving in for summer homes, constructing summer homes.”

Into the mid-1960s, Idlewild was an active year-round community and was visited by well-known entertainers. During the height of its summer season, it attracted African-Americans for camping, swimming, boating, fishing, hunting, horseback riding, roller skating, and nighttime entertainment.

Triplett says Black Wall Street Kalamazoo is hoping that through education and other efforts the financial gap between the Black and White communities gets smaller. Its website cites a 2016 statistic that indicates the average White family in the United States has a net worth of more than $171,000 while the average Black family has a net worth of just over $17,000.

“Hopefully when people see we want to continue to build on these examples of what we can do together and how much more we can be together – and if you pool your resources, and if you share your knowledge, and if you network – we’re hoping that all of these people come together to build a strong economic front,” she says.

A bit of history

Triplett says the name of her organization was inspired by the thought of the Greenwood District of Tulsa, Okla., an African-American community that was thriving in the early 1900s and was nicknamed Black Wall Street. In what has been dubbed the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre, the community was all but destroyed. And of some 800 Blacks reportedly injured on May 31 and June 1 of 1921, an estimated 300 were killed.

On those days, White residents of Tulsa and nearby counties attacked Greenwood and its residents (including the use of bombs thrown from airplanes) following a brief skirmish between White and Black men outside a county courthouse. According to information published by the Tulsa Historical Society and Museum, an exaggerated newspaper account of an encounter between a Black man and a White woman on a downtown office elevator on May 30 resulted in residents of the area assuming that the Black man had assaulted the woman.

Prior to the destruction, Greenwood was an affluent community. Jim Crow laws made Blacks unwelcome at many White-owned establishments. So Blacks developed their own stores, restaurants, schools, banks, and professional service providers, allowing the families in Greenwood to enjoy a higher quality of life than residents of some other areas.

“When you think about building generational wealth and having an area where we’re self-sufficient, it (the name Black Wall Street) just made sense,” Triplett says.

Although a Black Wall Street Muskegon has been started since Triplett got going, she says her organization is not affiliated with it or any other similarly-named organization.