Battle Creek poised to capitalize on momentum as it moves into the future

Here's look at some of the people and events that make Battle Creek the city it is today and some ideas about where it's headed.

Editor’s note: This story is part of Southwest Michigan Second Wave’s On the Ground Battle Creek series. Southwest Michigan Second Wave’s “On the Ground Battle Creek” series amplifies the voices of Battle Creek residents. In the coming months, Second Wave journalists will be in Battle Creek neighborhoods to explore topics of importance to residents, business owners, and other members of the community. Neighborhood coverage, telling the untold stories of those moving the community forward begins next week in Washington Heights. To reach the editor of this series, Jane Simons, please email her here or contact Second Wave managing editor Kathy Jennings here.

A former Battle Creek city commissioner once remarked that “Battle Creek has everything we need, it’s just missing that something.”

Depending on who you talk to in this city of 52,347 residents, that “something” includes everything from neighborhoods in need of improvement to better-paying jobs to more retail and restaurants to a downtown district that attracts and keeps people in town after the workday is done. The same sentiment is expressed by residents in cities throughout the United States.

Though some residents may see a “glass half full scenario”, city and economic development leaders point to a vibrant restaurant scene that includes Umami Ramen and the recently-opened Shwe Mandalay, a Burmese restaurant, as reasons to see the glass half full. They also tout Binder Park Zoo, the River Valley Trail, and recreational opportunities along the Kalamazoo River.

“I see a lot of resources and opportunities here,” says Joe Sobieralski, president and CEO of Battle Creek Unlimited, Calhoun County’s economic development agency.

In the beginning

Though the name conjures a fierce combat, the legend is the city’s name came from land surveyors who saw a creek and got into a skirmish with one or two Native American’s while they were scoping out the potential for development in the early 19th century. The so-called battle became part of the city’s iconography that has recently been slated for removal out of respect for the Nottaweseppi Huron Band of the Potawatomi.

George Livingston, retired Willard Library librarian and Battle Creek historian, says surveyors would hack off part of a tree with an ax to mark a boundary when they came to a particular section. Their activity drew Native Americans, setting the stage for conflict. Back in those days, Livingston says, surveyors often marked their maps with the location of every single pond and were running out of names for geographical features.

“For novelty, they called it Battle Creek because of the nearby creek,” Livingston says.

At that time, any waterway was a valuable piece of property because it meant flowing water and that meant power and industry.

“People in the East who were trying to eke out a living came here as did capitalists in big cities when they found out about the prominent waterways,” Livingston says. The thought was that it could be a settlement because water would provide power to the community.

The Quakers were among the first to see the potential.

“They knew they could subdivide the land they purchased into lots and make their money back 100 times over,” Livingston says. “They were canny enough to get in on the ground floor. They knew Battle Creek would be a promising site for a city because of the water. They were forward-thinking men.”

Before there was cereal

Before Battle Creek cemented its place as the world’s cereal capital, Livingston says it was known for its production of agricultural implements and the city was home to a big tractor factory that manufactured “behemoth tractors” which required skilled men and transportation options to get the steel required to the area.

“Nobody was eating cereal because there weren’t grocery stores back then,” Livingston says. “One thing that makes Battle Creek so interesting is its connection with wider world. The tractors that were produced here were too enormous to use in Michigan and were made for the vast plains of the world in Canada, South America and even in Russia.

“Vladamir Lenin was interested in getting hold of Battle Creek tractors. Many a Battle Creek man went over to Russia and talked to Lenin and sold him tractors. Those tractors would drive and never stop.”

The advent of the railroads brought a new group of settlers to the city who would have a profound and lasting impact on Battle Creek.

The decision by the Seventh Day Adventists to settle in Battle Creek was the result of a search for a place where there were honest and hard-working people. Ellen G. White, the religious sects founder, drew others to settle in Battle Creek.

Not long after, the city was home to the mother church for the sect.

“Not many communities are the mother church for the sect,” Livingston says. “There was a huge printing press on Washington and Main which was the largest in the United States called the Duplex Printing Co. and they used to print all of the religious works for Adventists all over the world. That required unimaginable amounts of paper on some of biggest presses in the world.”

As the number of Adventists grew and grew, they wanted their own school and Mother White’s thoughts turned to creating a place where clean living would be encouraged and supported.

Livingston says Mother White took note of a very successful sanitarium rest lodge in New York State. She said she had gotten a message from God that this was the way the Adventist church should go — to preach healthy living.

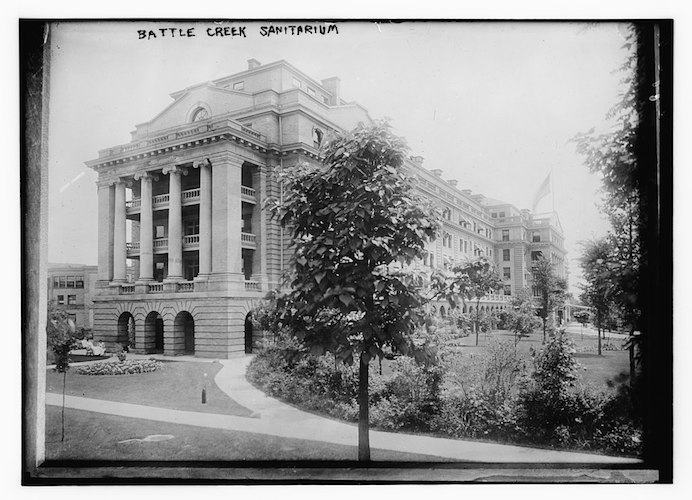

“The Sanitarium was built because of the Adventists,” Livingston says. “People were just drawn to it and Battle Creek became the best-known little town in America.”

The Sanitarium was a health spa and hotel which created the need for staff to attend to guests needs and other ancillary services. But, it also had a gymnasium which required exercise equipment and that’s when the exercise equipment industry began in Battle Creek, Livingston says.

Battle Creek becomes Cereal City

In keeping with the health-focused mission of the Sanitarium, a great deal of attention was paid to what visitors were going to be fed.

The steaks, oysters, and whiskey that were among the staples for so many menus of this time period were not going to fit with the Sanitarium’s mission, Livingston says. But, the case had to be made for what made certain foods better than others.

“This required that you had a doctor and a scientific lab to say why a steak is bad and lettuce is good,” Livingston says. “You also needed science and doctors to see how food burns up and how many calories are used.”

Mother White knew she needed someone to run what would fast become a popular industry — dealing with food — and she turned to the prominent Kellogg family.

She recruited John Harvey Kellogg and gave him a stipend to go to medical school.

Livingston says Dr. Kellogg had a theory about everything and always dressed in white and expected the same of the people who worked for him at the Sanitarium, which held tremendous prestige because of the famous doctors who would come there to work with Kellogg. The Sanitarium also served as a college which trained doctors and nurses.

W.K. Kellogg, John Harvey Kellogg’s younger brother, joined forces with his brother and was the organizational and marketing genius behind the Kellogg cereal empire after a recipe for that first type of cereal was perfected.

Livingston says visitors to the Sanitarium were fed a certain type of boiled wheat and somebody remarked that it was really good.

“They got so many compliments and after several experiments, they got something that people liked,” Livingston says. “Pretty soon, cereal became part of breakfast.”

It was that cereal that shielded Battle Creek from the worst of the Depression.

“The Depression came along and people still ate cereal,” Livingston says. “It was a recession-proof industry until the present day.”

Looking ahead

In the last decade, job reductions at the Kellogg Co. and Post Cereals have impacted the local economy; the closure of big box stores, especially at the once-thriving Lakeview Square Mall, has impacted shopping patterns; and the exodus of young people, who were raised in Battle Creek, to larger cities with more to offer, have created challenging times for the city.

Jim Hettinger, who guided the creation of the Fort Custer Industrial Park and served as president of Battle Creek Unlimited from 1979 to 2009, said in a recent interview that, “the Industrial Park becomes more and more important every day that the cereal industry recedes. What Battle Creek needs to do is have an honest planning process, a worst-case scenario process.”

The idea behind the development of the Industrial Park was to give Battle Creek an economic base that wasn’t dependent on the cereal industry, which has been in decline since the late 1960’s. City leaders also were looking to replace previous economic driver such as a military presence that had also been dropping off throughout the years.

The former military base that became the Industrial Park gave the city a place in the global restructuring of the economy.

While the Fort Custer Industrial Park continues to grow and thrive, the leadership of BCU, the organization responsible for the creation of the Park, says they are now broadening their scope to include other areas of the city.

Joe Sobieralski, president and CEO of BCU, says the city has been very, very successful on the economic development front with manufacturing and will continue to forge ahead with Industry 4.0, the name given to the current trend of automation and data exchange in manufacturing technologies, which includes the Internet of Things and cloud computing.

“We want to be a player in that space,” Sobieralski says, while acknowledging that the city has more work to be done on the community development side.

“The Industrial Park is diversified and has benefitted Battle Creek, but we need to create vitality for the downtown area and having places where people want to be outside of work,” Sobieralski says. “We want to keep people around, so they will lay their head here and call it home.”

A beautiful neighborhood

Lifelong Battle Creek resident Melvin Evans and his wife, Katie, never considered leaving Battle Creek. The couple moved into a home on Bowen Avenue in 1959 where they continue to live. When they moved in they were one of three Black families and the neighborhood was a place where neighbors took the time to get to know each other and took care of their homes.

“It was a beautiful neighborhood. I was one of the first people to start a Block Club here in the Heights,” Evans says. “We built a park on the corner of Howland and Bowen and we used to have Block parties that were smorgasbords just about. At that time things were fine.”

That park is named for Evans’ uncle, Claude Evans, who was the city’s first Black dentist.

About 10 years ago, Evans says the area started going down a bit as the result of young people buying homes without the financial means to keep them up. Evans says the slide was an issue that began in the 1970’s when the drug trade relied increasingly on the I-94 corridor to transport their goods between Detroit and Chicago.

“It damn near took over Battle Creek,” he says. “Drug dealers were setting houses on fire as a message to people who didn’t pay their bills.”

The neighborhood also saw its share of parties that got out of control, people parking on lawns, and a general apathy about the area. Things are turning around these days and Evans, now 87, says he’s never worried about his safety and intends to stay put.

“I had a job at Post and my wife worked at Kellogg and we raised a son here and the neighborhood was beautiful,” he says. “After I retired in 1996, we were thinking about moving, but the house is paid for and we stayed.”

Sobieralski says he wants more people to feel like Evans does. He says the city has a lot of resources and opportunities here and BCU wants to be an influence and make it a community that people want to convince their friends and family to move to.

This is what is driving BCU to take more of a lead role in addressing what he sees as a lack of basic principles for having a thriving community, such as nightlife and more dining options. He says that this is outside of the realm of what his organization has done in the past but says that his board and leadership team believe that the times demand a more inclusive approach to creating a vibrant city.

“We are intentionally inserting ourselves in the community development side. We can’t continue to grow our technology base without community development,” he says. “There needs to be a holistic approach to economic development. We can’t be working in silos.

“The economy is doing well, we’ve got the momentum and we’ve got to capitalize.”