Battle Creek voices shape Children’s Defense Fund agenda in 2024 election year

“We really want to make sure that the public policy advocacy we’re doing was grounded in the experiences of families we serve all across the country."

Editor’s note: This story is part of Southwest Michigan Second Wave’s On the Ground Battle Creek series.

BATTLE CREEK, MI — If children could vote, elected officials would likely be paying more attention to them and what they need and deserve, says Rev. Dr. Starsky Wilson, President and CEO of the Children’s Defense Fund, who held a listening session in Battle Creek on July 11 with community stakeholders.

“We really want to make sure that the public policy advocacy we’re doing was grounded in the experiences of families we serve all across the country,” he says.

The gathering, held at Kellogg Community College, was attended by families of students of R.I.S.E. (Reintegration to Support and Empower) Freedom School, and local nonprofit and religious leaders. It is one in a series of listening sessions that Starsky is doing throughout the United States which will aid in prioritizing a policy agenda developed by the CDF in 2023.

That agenda came together after listening sessions in 2022 and 2023.

“We created a new policy agenda launched in November 2023. Now, these more recent sessions will help us to prioritize how we enter into the next Congressional sessions and what will we focus on with our state offices across the country. We will prioritize where we put staff, volunteers, and organizers,” Wilson says.

Damon Brown, President and CEO of R.I.S.E. Corp, stands with Rev. Dr. Starsky Wilson, President and CEO of the Children’s Defense Fund

“We talk about the number of young people there are and how it would change the whole election if they could vote,” says Jacqueline Patrick-James, Director of the Student Empowerment Program and R.I.S.E. Board Treasurer.

If 16 and 17-year-olds went into the voting booth, they could vote to levy a tax for those changes, Wilson says, adding that how they vote would be entirely up to them, but they would at least get a vote.

There already are a few municipalities, among them Tacoma Park, MD., and Newark, N.J., that are giving 16-year-olds the right to vote in mayoral elections. Small steps that foreshadow what Wilson calls a “moonshot” for the CDF.

“One of the things we have listed as a moonshot goal is to lower the voting age to 16. This changes things like equity and inclusion,” he says.

Policymakers, pundits, and citizens continue to debate about what should be the proper voting age, according to an article on Ballotpedia.

“Proponents of lowering the voting age argue that 16-year-olds should be permitted to vote because decisions made by the government affect them, too. Meanwhile, those who advocate maintaining or raising the current voting age voice concerns about the ability of younger individuals to make mature, well-informed decisions at the polls,” according to the article.

James says the absence of having a voice or revenue source behind them makes it all the more important to have CDF in their corner.

Among the ideas she put forth at the listening session was the creation of a designated fund for children similar to what is available for older adults within the State of Michigan’s budget.

“We need to invest into our kids financially so that we can fix the schools and offer them a better quality of life. We need to write them into the state budgets. There should be a Kid Fund.”

Other ideas put forward included policy changes around work schedules and maternity leave.

“Parents are trying to work full-time just to maintain a household. They don’t have a lot of additional time to parent,” says Felicia Mares, Community Relations Director for CityLinc. “We need more robust maternity leave and benefits for stay-at-home parents. We say we want more parental involvement, but that comes at a cost somewhere else. We need policy changes that offer more lenient PTO (Paid Time Off) and flextime which may mean changing working hours.”

LaJoy Agnew, who has two children in the R.I.S.E. Freedom School, says if you have your finances right, it eliminates a lot of scarcity issues and gives you a security blanket.

“If you have a good job, you can afford the best childcare, It opens up more opportunities to do what most people can’t do,” she says.

Three questions, a flurry of Post-it notes

Wilson asked participants in the listening session to answer questions including: What is happening in their community or the world that makes it hard to raise children and what should we be doing to make change for the children? What did you see that requires us to act differently before we can make change?

These are the same questions being asked at all of the CDF listening sessions.

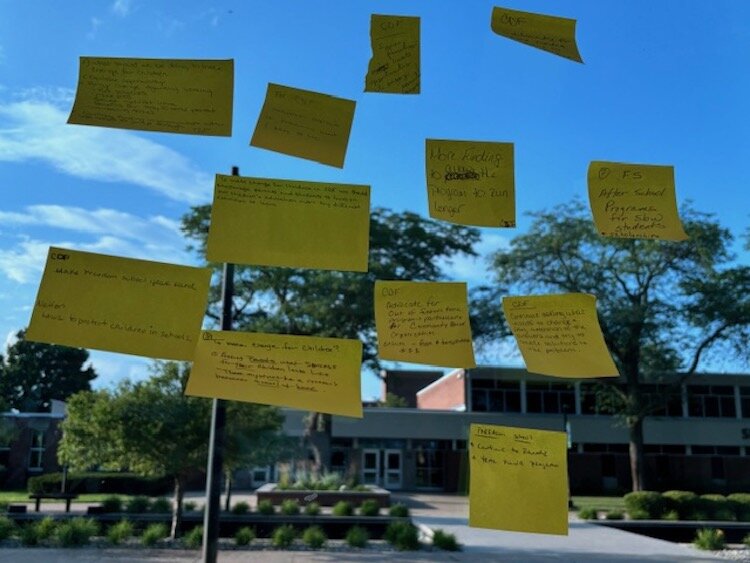

Participants wrote their responses on post-it notes that they attached to windows in KCC’s Binda Performing Arts Center where the gathering was held.

Post-it notes with answers to questions asked during the listening session were attached to windows inside Kellogg Community College’s Binda Center for the Performing Arts.

Marcus Patrick, who has two children attending the R.I.S.E. Freedom School, says resources need to be made available to benefit youth through activities they want to be involved in such as community recreation opportunities or arts programs.

“Sometimes, we as adults say things that we think they want to do,” Patrick says in response to that first question.

Agnew, says she’s OK with the academics, but the social aspects are giving her cause for concern.

“My oldest is about to go to middle school to a school that’s out of district and not predominantly black. It’s hard trying to get the priorities straight with the academics and then you have the socialness aspect to deal with.”

Her comment was supported by other parents who have children attending predominantly white-populated schools.

Having programs like the Freedom School gives children opportunities to be with other children who look like them, says Jasmine Arms, mother of two Freedom School participants.

“Our children are targeted based on who they are and what they look like. It’s hard to manage that,” says Mares, who has two children in Freedom School.

Much of this targeting comes through social media, says Damon Brown, Founder and CEO of R.I.S.E.

“Social media is a thing for the kids. If they’re not on it, they’re being bullied. The most important thing to do is to talk to our kids because they’re being exposed to so much at a younger age,” Brown says. “Kids are very, very mature and receiving a lot of information at a younger age.”

One parent said she’d like to see every Sunday School and public school integrate the Freedom School concept so that it would be a more year-round opportunity.

This begs the question, “How do we lean into educators so that it lives in a way that’s year-round,” Wilson says. “We need to consider school standards.”

Mary Mulliett, President and CEO of the Battle Creek Community Foundation, foreground, and Jacqueline Patrick James, Director of R.I.S.E.’s Student Empowerment Program and Board Treasurer, giving written responses to questions.

Brown says the way children are educated has not advanced at a pace similar to automobiles and telephones.

“Cars and telephones have advanced from their earliest versions. Most of our classrooms haven’t and look exactly the same. Some of the books I’ve seen at Northwestern Elementary School are the same as when I was there,” Brown says. “The way we’re teaching our kids is so old-fashioned.”

“We have commodified public schools and made it into workforce development programs,” Wilson says. “Conversations about how people should be educated should not be driven by corporations. They should be ruled by mamas and big mamas.”

He cites Texas students who have faced increasing restrictions in recent years on their education, from limiting discussions about race and gender in the classroom to regulating books in school libraries. The latest move by Texas politicians is hidden in plain sight under an existing 2021 ban that targets the teaching of “inherently racist, sexist, or oppressive” groups,” says an article on the law, HB 3979, also prohibits schools and teachers from requiring or awarding credit for “direct communication” between students and their local, state, or federal politicians.

“One in ten children in the United States are born in Texas. What happens in their educational system impacts the country. What is happening there has the impact of reducing the civic engagement of Black and Brown students once they graduate. They don’t engage and they don’t volunteer,” Wilson says.

Bringing their message to a friendly city in a battleground state

Battle Creek was among the sites selected based on the presence of a CDF Freedom School operated by R.I.S.E. This is how locations in other areas of the United States were also selected.

But this isn’t the only reason, says John Henry, CDF Media Relations Manager.

“Additionally, we were interested in listening to parents in battleground states, like Michigan, and visiting school sites that have been a part of the CDF Freedom Schools program for a while and have deep roots in their communities,” he says.

In addition to Michigan, other battleground states that are on the CDF’s radar are Georgia, Nevada, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, and “one can argue, Ohio,” Wilson says.

The local Freedom School is now in its third year of operation through R.I.S.E. with more than 25 area youth participating, Brown says.

Damon Brown, Founder and CEO of R.I.S.E. Corp., at left, poses with Jacqueline James Patrick, Director of R.I.S.E.’s Student Empowerment Program and Board Treasurer, and Rev. Dr. Starsky Wilson, President and CEO of the Children’s Defense Fund, at a

CDF Freedom Schools provide summer and after-school enrichment through a research-based and multicultural program model that supports K-12 scholars and their families through five essential components, says the CDF website. The schools are an outgrowth of the Mississippi Freedom Summer Project of 1964.

“We focus on high-quality academic and character-building enrichment, parent and family involvement, civic engagement and social action, intergenerational servant leadership development, nutrition, health, and mental health,” says information on the CDF website.

R.I.S.E.’s six-week Freedom School began on June 17 and concludes on July 26. It is a literacy program that integrates reading, conflict resolution, and social action in an activity-based curriculum that promotes social, cultural, and historical awareness, Brown says.

CDF Freedom Schools, Wilson says, “incorporates the totality of CDF’s mission by fostering environments that support young people (known as “scholars” in the program) to excel and believe in their ability to make a difference in themselves as well as their families, schools, communities, country, and world with hope, education, and action.”

Since its inception 30 years ago more than 200,000 young people have been touched as scholars at Freedom Schools which operate in 100 cities and the District of Columbia, he says

For five years, Minister Roxie Perry, with Second Missionary Baptist Church, led the first Freedom Schools in Battle Creek. She attended the listening session to offer her input on what could and should be done to create better outcomes and future success for the community’s youngest residents. She spoke about the lasting impact of Freedom School on its scholars, many of whom became servant-leader interns in the program.

“So many servant leader interns from Battle Creek are principals and heads of schools now. The energy they had as interns, you can still see it now as they are heading schools,” Perry says. “I bet I could go and visit with these young now people and say ‘Freedom School’ and they’d break out with the cheers and chants they learned while there. It stays inside of them.”

These servant leaders are putting the lessons and leadership skills they learned to work in all sectors, including the Federal government.

“These legislators that we see on Capitol Hill don’t know that we’re training their staff,” Wilson says. “The people running Congress are all under the age of 35.”

Successful outcomes for scholars in the Freedom Schools are among the wins for CDF. The organization’s advocacy work also has resulted in wins, most notably the passage of the federal CHIP (Children’s Health Insurance Program) signed into law in 1997 and the expansion of the Child Tax Credit enacted that same year.

While the CDF is a nonprofit that doesn’t take political positions, the CDF Action Council is governed by an eight-person Policy Council and is registered as a 501(c)4 social welfare organization in the District of Columbia.

Wilson says the CDF Action Council advances child well-being through grassroots lobbying, advocating in Congress and in statehouses for child-centered policies, and holding elected officials publicly accountable for supporting those policies. Its signature, nonpartisan Legislative Report Card informs the American public about members of Congress’s activity across a range of issues impacting children.

Further evidence of the CDF and its lobbying arm to impact the lives of children occurred during a 2016 Presidential debate when there was a question about child poverty, Wilson says.

Prior to this he says, “We were not talking about children in a presidential debate. This was the first question like that in 25 years.”

This week he’ll be meeting with 450 faith leaders from throughout the United States to make a case for discussions about children’s policy from their pulpits. This gathering will take place at the CDF’s Haley Farm named for Alex Haley, who wrote the book “Roots”, among other best-selling novels. Since 1994, the Farm has hosted Freedom School trainings.

“This is what we do,” Wilson says of CDF. “We stopped making children our only source of intervention, The community has to be a source of intervention as well. We can’t just focus on the seed or soil, we have to till the soil. We have to change policies around children so it’s more likely they will flourish.”