On Thursday, the SHARE Center,120 Grove Street, is hosting an Open House from 5 to 7 p.m. to showcase the many services it offers to help vulnerable individuals and families in the community.

Editor’s note: This story is part of Southwest Michigan Second Wave’s On the Ground Battle Creek series.

When children come in with their families for a meal at the SHARE Center, Robert Elchert wants them to feel like they’re dining at a restaurant, not a “charitable meal site.”

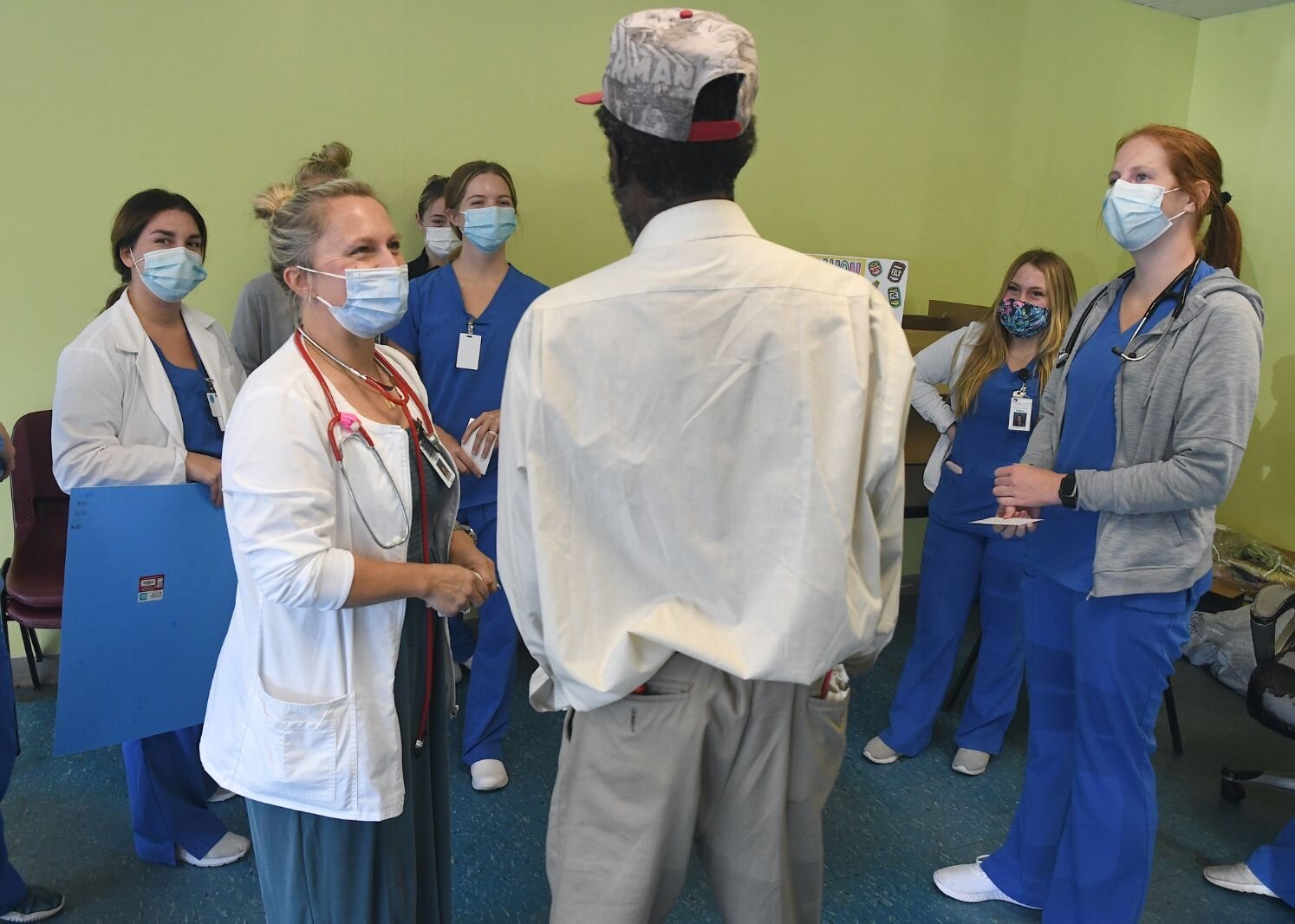

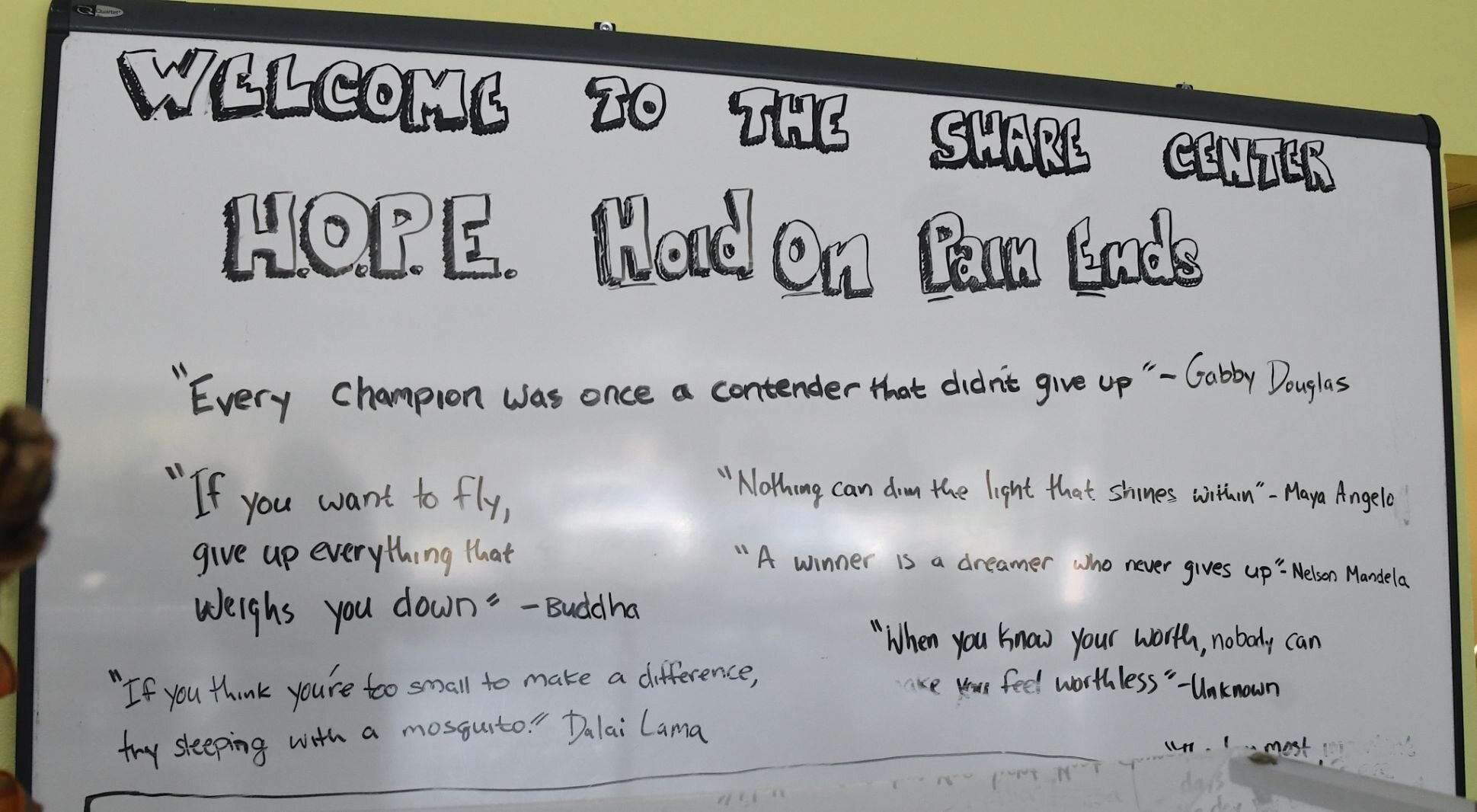

Elchert, Executive Director of the SHARE (Self Help Awareness Recovery & Enrichment) Center, says living in poverty takes a psychological toll on everyone who lives that reality and he wants to make sure his organization offers support and resources with empathy. The goal, he says, is to restore dignity while working to lift people out of poverty.

In addition to the services and resources the SHARE Center already offers, Elchert says he also is doing what he can to address a growing need for housing for those who are homeless families and individuals, especially the clients served on a daily basis through the SHARE Center.

“We are working with a family through Neighborhoods Inc. We’re trying to keep them in a hotel until we can find housing for them,” Elchert says, citing just one example. “We either find a hotel for them or they sleep in their car. This is a family of four with service animals and this living arrangement is not ideal. The longer their kids stay in that environment, the greater the likelihood that they will end up in poverty. We have to break that cycle.”

On Thursday, the SHARE Center, located at 120 Grove Street, is hosting an Open House from 5 to 7 p.m. to showcase the many services it offers to help vulnerable individuals and families in the community. Compared to other nonprofits in the community, the SHARE Center provides the “lion’s share” of free breakfasts, lunches, and dinners to anyone in the community seven days a week, Elchert says.

In 2020, just over 30,000 meals were served in a cafeteria on one side of the 10,000-square-foot building that formerly housed an auto parts store. Elchert says he is hoping to get funding through grants to make the cafeteria space a hub for homeless services focusing on families when it is not being used to provide meals.

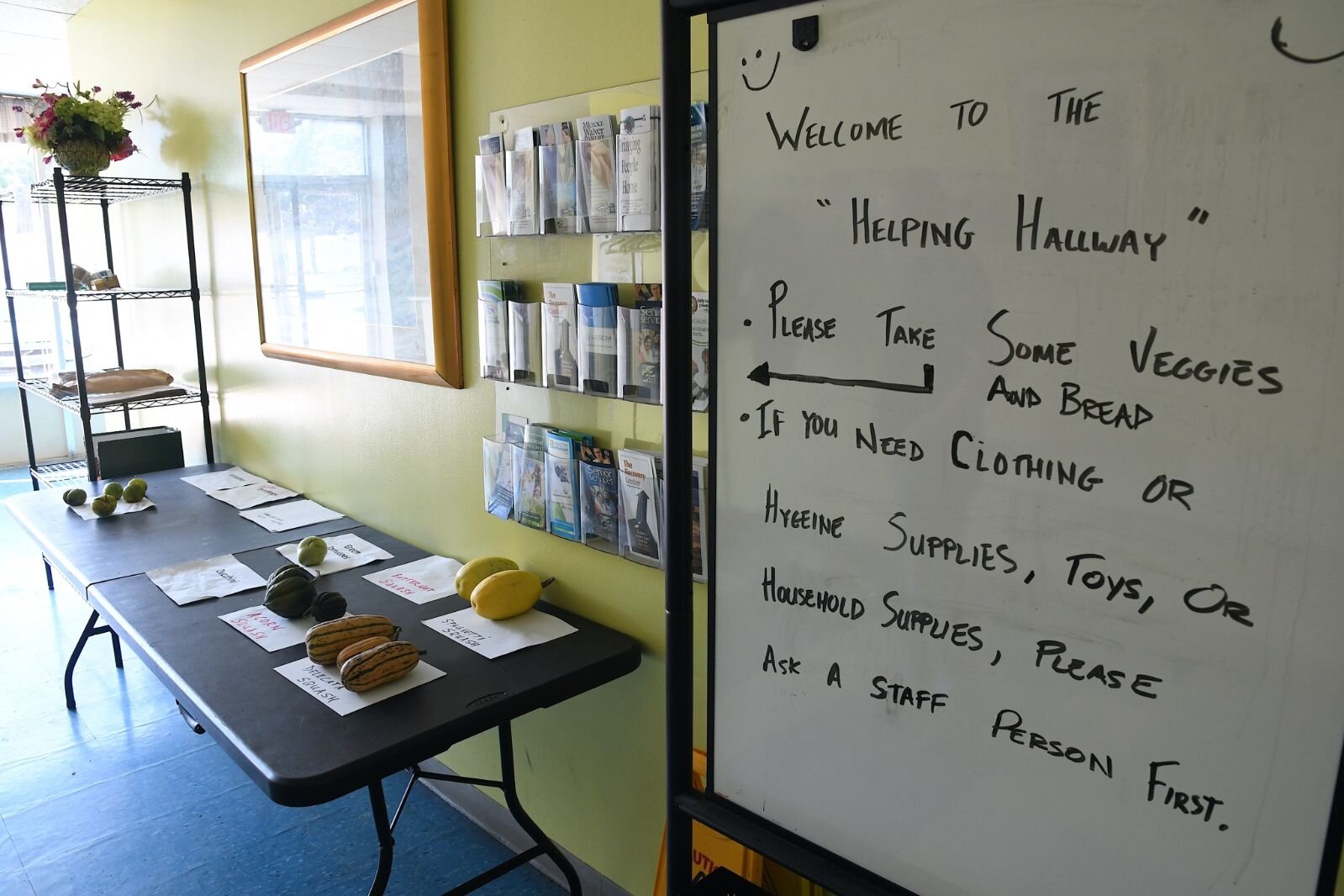

Currently, families are only able to access limited services such as obtaining clothing and household items. He says he is always looking for donations to stock an area of the building set aside to house these items.

When not in use as a community meal site, the cafeteria serves as a destination for homeless individuals to access resources and services to have their basic needs met. They can secure a state I.D. and access vital records; receive employment and benefits coaching; get city bus passes; get laundry done; and get clothing, blankets, and personal hygiene items.

The annual budget for the SHARE Center is about $500,000.

“A good chunk of that comes from Summit Pointe to fund the drop-in center,” Elchert says. “The cafeteria side is funded through grants and donations.”

The nonprofit organization was founded in 1992 by a group of individuals who had real-life experiences recovering from mental health and addiction issues. Today, the overwhelming majority of the 3,500 clients served annually by the SHARE Center are homeless individuals with mental health and substance abuse issues.

They come to a drop-in center, separated by walls and doors from the cafeteria side of the building. Currently, that center is available only to homeless individuals, not families, and Elchert says he is working on a grant that would provide funds to hire a case manager to work with homeless families to secure housing, among other needs.

“If they don’t have a place to move into that they can afford, their choices are very limited,” Elchert says. “With part of our focus being on families, we can provide them with items like diapers, baby formula, food, and crayons and coloring books to make it better for kids so they could remember this as a positive place. We also have pots and pans and clothing for kids and adults so that families don’t have to spend money on those things and can spend that money on housing.”

Elchert says the drop-in center is technically a mental health facility funded by Summit Pointe.

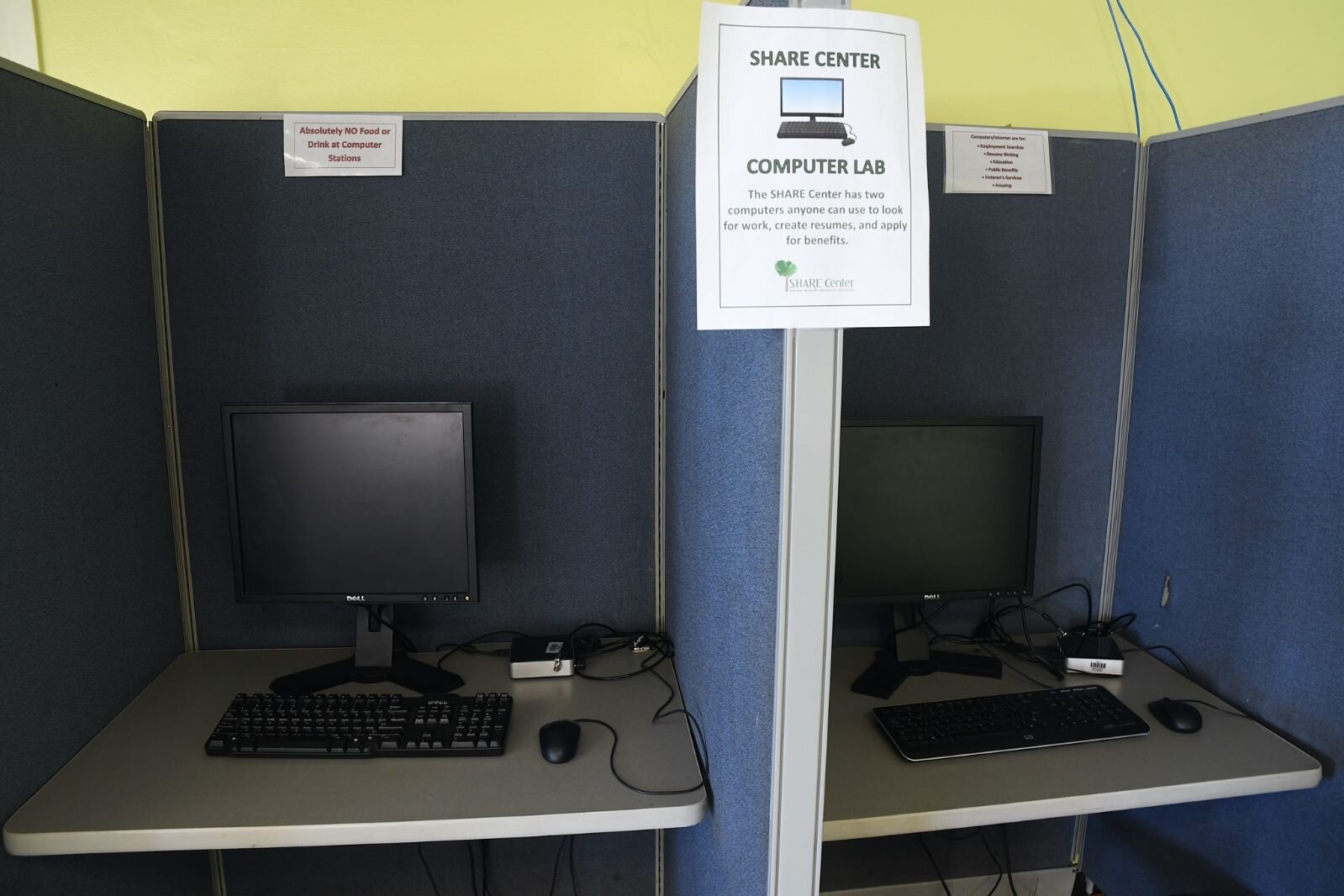

“That drop-in center includes Peer Support Recovery coaches who work with individuals one-on-one or through support groups for women, men, and veterans. There also are group meetings for those with mental health and addiction issues,” Elchert says. “We also offer enrichment activities like yoga, gardening, life skills, art and music, and a computer lab.”

The peer-run model means that everybody who works at the SHARE Center and its board members have had some experiences with the mental health system.

“If you’ve been through it, you’re a lot more invested in our work than someone else who has not been through it,” Elchert says. “It helps to have a staff who were consumers of the mental health system because they know the barriers and are less likely to be judgmental. Some of the trauma is so severe, that the average person would never begin to understand it.”

At 19-years-old, Khyrinn Herring is the board’s newest and youngest member. And she struggles with her own mental health issues.

Herring says her father struggles with PTSD (Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder) which began during his time in the U.S. Marines. His family, she says, has a long history of bipolar disorder and schizophrenia.

“Science can’t tell you if it’s hereditary, but that does set up your children and that kept him away,” Herring says. “He was never around and I ended up having mental issues of my own. It was a rough journey and it hasn’t always been pretty. I have a strong support system, but I know that a very thin line separates me from people who can’t keep a job or housing or their kids. For some of these people, no one was there for them. I know what it’s like to go through a manic episode or what it’s like to not have access to meds. It’s hell.”

Herring says being supported by people who offer empathy instead of pity is what sets the SHARE Center apart from other organizations doing similar work.

“The purpose they serve is to bring back humanity when it comes to dealing with people and bring to the table what connects us all as human beings,” she says. “What it takes to truly help someone is not a cot and three meals a day, it’s having conversations and getting them help and continuing to see through that and making sure that they’re getting help from someone they trust who has their best interest in their heart.”

Providing a temporary safe zone

The drop-in center is intentionally designed as a safe space where people can get away from drugs and alcohol and deal with their mental health issues. They can also access services designed to support their efforts to break the cycles of addiction and poverty that bring them in, Elchert says.

For some of those they serve, especially those dealing with mental illness, the likelihood of ever becoming what others consider a productive member of society will never happen. That’s a reality that Elchert and his staff and volunteers resign themselves to on a daily basis. During the day, the SHARE Center is home to them and those individuals who are able to manage their addictions and mental health.

When the doors to the building close at 7 p.m. each day, Elchert says, they disperse. “They could be staying in other shelters that offer overnight stays, in the woods, or under bridges. I think the homeless population is largely invisible. They tend to hang out in the SHARE Center and other places (during the day) and you don’t really see them unless they’re panhandling,” he says. “I think the pandemic has opened people’s eyes to just how big the homeless population is and at that point the city said ‘We have to do something about this.’”

In late August, city leaders and representatives with UPHoldings, a Chicago-based affordable housing and development company, met with community residents at the SHARE Center to discuss plans for a 40- to 60-unit housing development somewhere within the city limits.

This development will be designed for permanent supportive housing, says Battle Creek Assistant City Manager Ted Dearing. While UPHoldings continues its interest in working with the city on this development, Dearing says the key part will involve locating a site that will work for UPHoldings and be a good fit for the community.

He did not offer any type of timeline and said, “We’re going to take a step back and spend more time getting more familiar with the characteristics of permanent supportive housing.” This would include who the tenants are and what the funding mechanisms would be. “We are planning a workshop in the near future with the City Commission to talk about those issues.”

Elchert says a development like the one under discussion would provide the type of housing that is needed for clients served through the SHARE Center.

“Permanent supportive housing is literally permanent,” he says. “People who qualify would have access to an apartment and supportive services needs in that building, which would include on-site caseworkers and social workers.”

Given the most recent statistics and what Elchert sees on a daily basis, he says, “It’s an emergency situation that needs to be addressed with the provision of housing for the individuals served at the SHARE Center. I think we could use at least 10 of these permanent supportive housing developments.”

In 2020, there were 732 people experiencing homelessness, according to the Battle Creek Homeless Coalition Homelessness Report. Of those people, 402 have a disability, and 186 have been living without fixed housing for more than 12 months.

Elchert suspects that this is not a complete or accurate count because oftentimes homeless people are difficult to track down and don’t want to be found. “If their needs are being met by service providers, they won’t draw attention to themselves,” he says.

The lack of permanent supportive housing is fast becoming a major frustration for Elchert who says because the SHARE Center is not considered an emergency shelter, it doesn’t have access to larger state and federal grants that would enable it to offer some type of stopgap shelter until people find permanent housing.

“We see a lot of Veterans, senior citizens, and children and it’s hard to accept the fact that this is where we are as a society,” Elchert says. “I look at my life and I think how hard a behavior change is going to be in the best of times. To expect a homeless person to overcome mental health and addiction issues, while also dealing with homelessness is a backward model. They would have more success if they were in a stable housing situation and away from stimuli on the street.”