Battle Creek police and area agencies find the benefits of working together for the community

Since 2014 the Battle Creek Police Department and a number of area agencies have been working together to improve how cases are handled. Now they have funding to expand their work.

Editor’s note: This story is part of Southwest Michigan Second Wave’s On the Ground Battle Creek series.

A collaboration among community organizations and the Battle Creek Police Department has streamlined the way officers respond to calls while providing the resources that better address the needs of those making those calls.

Known as the Fusion Center, the collaborative began in 2014 without much fanfare and it is enabling officers to focus on calls involving criminal activity while giving representatives with organizations such as Summit Pointe and Safe Place the ability to address the needs of residents who seek out the police as their first line of defense.

Summit Pointe helps individuals with mental health issues and developmental disability reclaim their independence, regain confidence and learn the skills necessary for success. The agency also provides education to enhance individual skill levels and help individuals realize their potential. Safe Place provides shelter and resources to domestic violence survivors. The two organizations’ individual areas of expertise are helping the Battle Creek police as they respond to cases that require special knowledge that police have not been taught.

Today, the Fusion Center’s Resource Center also has representatives from the Veterans Affairs Medical Center, the Share Center, and agencies that work on homeless issues, Juvenile Probation, and Homeland Security. They come together in a dedicated space on the second floor of the BCPD headquarters to share information and ideas depending on the nature of a case or issue they’re dealing with.

While an officer will always respond to a call for service, Battle Creek Police Chief Jim Blocker says about 70 percent of the time these calls are determined not to rise to the level of serious criminal activity. They are instead, he says, requests for service that may involve an individual with mental health issues, a child who is acting out, or an overdose victim.

“When an officer shows up at my house and I had called 911 because one of my children is having a traumatic mental breakdown, it may have been a 911 call, but can you tell me what’s criminal about it?” Blocker says. “In the past, an officer will show up and give them a crisis line number. Now, we actually have the clinicians and we know them by name and the officer can contact them directly to get help for this family.”

Summit Pointe has dedicated a professional to work half-time in the Fusion Center. The organization also has staff on call 24-hours a day who will respond to a call from an officer who is dealing with an individual with mental health issues.

“It’s remarkable to us that individuals don’t realize the resources that are available to them in the community,” says Melinda Holliday, Crisis Clinician with Summit Pointe. “Police officers are not always aware of what individuals are needing or seeking. We recognize those individuals.”

Holliday says her organization has seen an increase in their workload as a result of their work with the Fusion Center but adds that they have been able to be more effective because of the streamlined process which is enabling individuals to access the resources they need.

Prior to the creation of the Fusion Center, Blocker says the participating agencies and organizations each worked in their own silos.

“When we think of the criminal justice system we think it’s a well-oiled machine. It’s actually a loose-knit community attached by function. There’s no requirement for me to work with Summit Pointe,” Blocker says. “The Fusion Center was built upon an accidental partnership as we were looking at how we could connect agencies that have all of this capability and information and how we could come together to resolve the issues we deal with.

“If we’re in a room together, now it’s personal. We know each other and we are willing to listen to one another. All of these organizations have voluntarily dedicated staff who are working within this facility. Complex problems require critical thinking and answers that may not be readily available to an officer on a patrol call.”

Before the collaboration, police officers sometimes didn’t like to deal with community mental health staff at various agencies, says Sgt. Jeff Case, who leads the Fusion Center.

“We had to look at ourselves and evaluate how we could do a better job with community mental health,” Case says. “It used to be that we knew we needed a clinician to come out to a house where we were responding to a call involving a mental health issue, but the officer may have had five calls for service holding and didn’t know how to get a clinician response set up.”

The work already going on with BCPD and Summit Pointe led to the creation of a local Crisis Intervention Team program that is designed to improve officers’ ability to safely intervene, link individuals to mental health services, and divert them from the criminal justice system when appropriate.

Blocker says the Crisis Intervention Team approach was the direct result of the recognition throughout the United States that a better job had to be done to deal with a growing mental health crisis.

“The three largest mental health providers in the United States are Rikers Island, the Cook County Jail and the Los Angeles County Jail,” Blocker says.

In the two years since the Crisis Intervention Team program began there have been 606 CIT calls. Prior to the training, Blocker says they all would have gone to the police department to handle, with most resulting in an arrest because many officers did not have an understanding of what was really going on.

“That’s 606 individuals who could have been in jail; 105 of them had committed arrestable offenses and could have gone to jail right away,” he says of the Crisis Intervention Team calls. “But, our officers are now able to divert them and get them the help they really need.”

Of those who had committed arrestable offenses, nine ended up in jail.

Officers have also learned how to better handle cases when a mentally ill individual is involved. “When Jeff and I went to the police academy, we were taught right away to close the distance, but when you’re dealing with someone with mental illness that just makes them worse and they get physical and then they’re arrested for assaulting an officer,” Blocker says. “Now they (officers) know what the signs and symptoms are.”

There are 62 Crisis Intervention Team-trained law enforcement officers in Calhoun County, 21 of whom are with the BCPD. They were trained by professionals with organizations including Summit Pointe, the National Association for Mental Illness, and area hospitals. Summit Pointe coordinated the training.

This training also includes an emphasis on officer wellness. Meghan Taft, who works at Summit Pointe and is the Crisis Intervention Team Coordinator, says officers are brought in every quarter for two hours with a focus on wellness training.

“We knew we would be remiss if we didn’t encourage officers to take their own wellness steps,” Taft says.

The work of the Crisis Intervention Team will be able to continue and expand thanks to $1 million in funding through the U.S. Department of Justice that was announced recently. The funding comes in two grant awards: $750,000 received in collaboration with Summit Pointe, under the Justice and Mental Health Collaboration Program and $276,000 for law enforcement-based victim specialist program, intended to help victims of violent crime navigate the criminal justice process.

The $750,000 grant “will allow our CIT program in Calhoun County to expand, with an emphasis on the youth in our community,” says Jeannie Goodrich, CEO of Summit Pointe.

Police plan to focus attention in particular on local schools and young people. Blocker says the program is designed to work with young children to identify those who are suffering from mental illness caused by early age trauma or other factors.

“I had a very narrow, naive view of what law enforcement was. I now recognize how complex it is and how much they have on their plate and that we’re all trying to do the same thing,” says Holliday, who works with the Crisis Intervention Team program.

The lack of coordination and collaboration that existed before the Fusion Center was established was not unique to agencies dealing with mental health issues. Case says the BCPD knew they needed to establish better relationships with those agencies as well.

As one example, the police have ramped up immediate access to professionals including those who deal with drug overdoses in Battle Creek, a problem that has increased markedly here as it has in communities throughout the United States.

“We can go out and address these calls, but we are not the people equipped to take care of overdose victims,” Case says. “We’ve tried to provide them with resources so that these crises don’t continue to happen. Sometimes we’d go out to the same house and address an overdose issue 15 times in the same week, but it’s not a criminal issue, and we can now stop going to the house because we’ve provided tools for them to address the problem.”

The same is true with incidences that necessitate the involvement of Child Protective Services. Prior to the formation of the Fusion Center and established relationships among agencies, Case says it was not uncommon for officers to mount a full-scale raid on a home because they didn’t know what they might be dealing with. Because there is now a stronger relationship with CPS, Case says the BCPD has an identified CPS representative who they can call as the need arises.

“We are able to get folks there faster and plugged into what’s going on because we have people we know that we can go to and they can come to us if they think it’s a criminal matter,” Case says.

Having this type of direct response from a community agency is significant, particularly with domestic violence cases where the victim is in an incredibly vulnerable state and doesn’t want to reach out to law enforcement, Blocker says. These cases frequently merit involvement from representatives with Safe Place, another Fusion Center partner.

The Fusion Center is an extension of various partnerships the BCPD entered beginning in 2014 with the inclusion of an embedded parole officer. This initiative was introduced by former Gov. Richard Snyder in 2012 and was designed to place parole officers through the Michigan Department of Corrections in more cities throughout the state, including Battle Creek.

That first embedded parole officer worked out of the BCPD headquarters and served as a liaison between officers while managing the workload of her clients who were parolees.

“In Battle Creek, we have a large parolee population,” Blocker says. “What’s even more remarkable is that with that population oftentimes we don’t know who they are or where they live. It’s not as routine as you might think. She really started working with officers and other local law enforcement when it came to folks on parole.”

The embedded parole officer was always accompanied by an officer when going to homes, places of employment and other sites where parolees may be located and she also was responsible for ensuring things such as offender compliance with supervision conditions; engaging their significant others; checking for substance abuse; and investigating allegations of new criminal behavior.

Blocker says the embedded parole officer gave his department a much better understanding of where the community’s parolees were located and how his officers could better understand and assist them.

Case says this also helped to create a better working relationship between the department’s Gang Unit and Parole and Probation. “There were things we knew that they didn’t know and visa versa,” he says.

This partnership with the state’s Department of Corrections, which continues today, got Blocker thinking about who else the department could partner with to increase their understanding, provide more focused training opportunities to officers, and better serve the community’s residents. His outreach resulted in the current Fusion Center collaborations that have yielded better than anticipated results.

One example involved a human trafficking case in 2016 that was successfully addressed with input from CPS, Juvenile Probation, and the BCPD.

Case says two young women who were the victims of human trafficking were known to both Juvenile Probation and CPS. “When this call came in via someone we knew, the entire room got to work on it,” Sgt. Case says.

The girls were found within hours of the call coming in and removed from the trafficking environment. Within nine days the men in charge of the human trafficking operation were in federal custody and charged a short time later.

Five years ago, Case says, it likely would have taken longer to locate the girls and arrest the perpetrators because CPS and Juvenile Probation often operated without communicating even though they may have been dealing with the same incident.

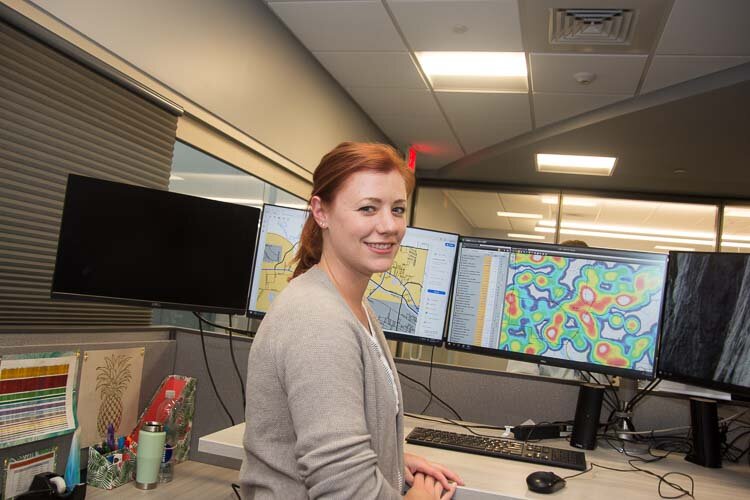

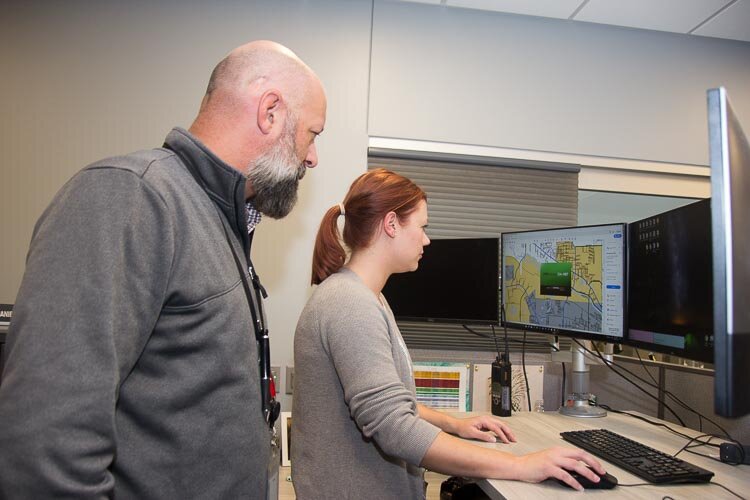

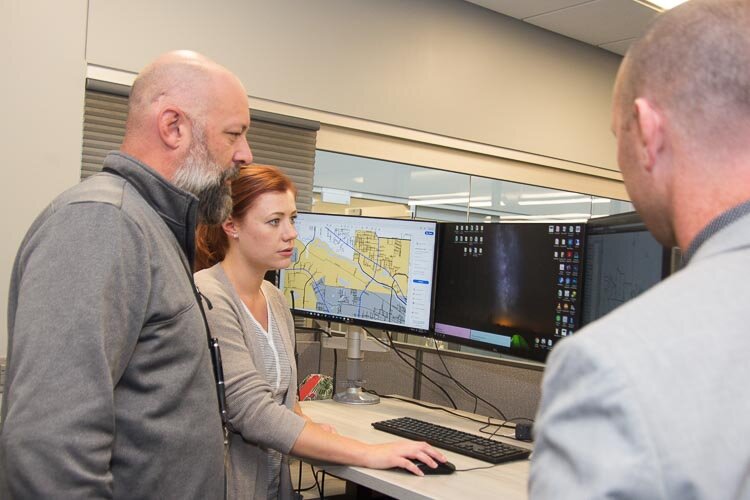

Two analysts, one full-time and one part-time, also work out of the Fusion Center to provide the BCPD with a better idea of potential areas of criminal activity or geographic areas that they should be focusing on to prevent crimes. Case says this eliminates previous scenarios that found officers “flooding” neighborhoods in a non-strategic way.

The analysts who have been part of the BCPD since the mid-2000’s understand what’s going on in the city and issue daily reports that can direct officers to specific areas, he says.

“When big things happen,” Case says, “we collectively work with our Battle Creek teams and community partners to solve the problem very quickly.”