Area artists, 25 local groups come together as KIA hosts only Midwest stop of ‘Black Refractions’

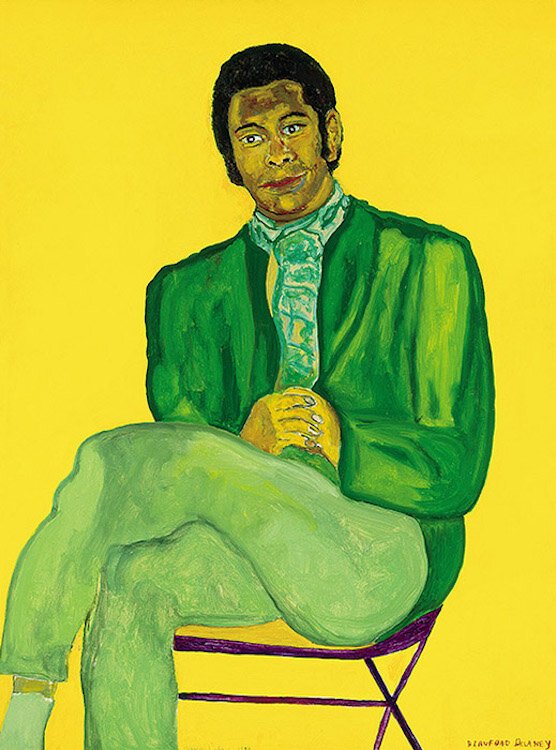

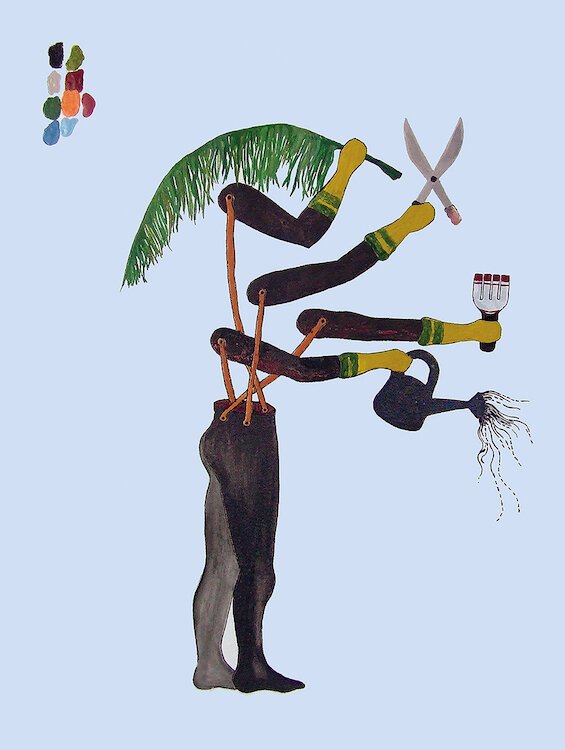

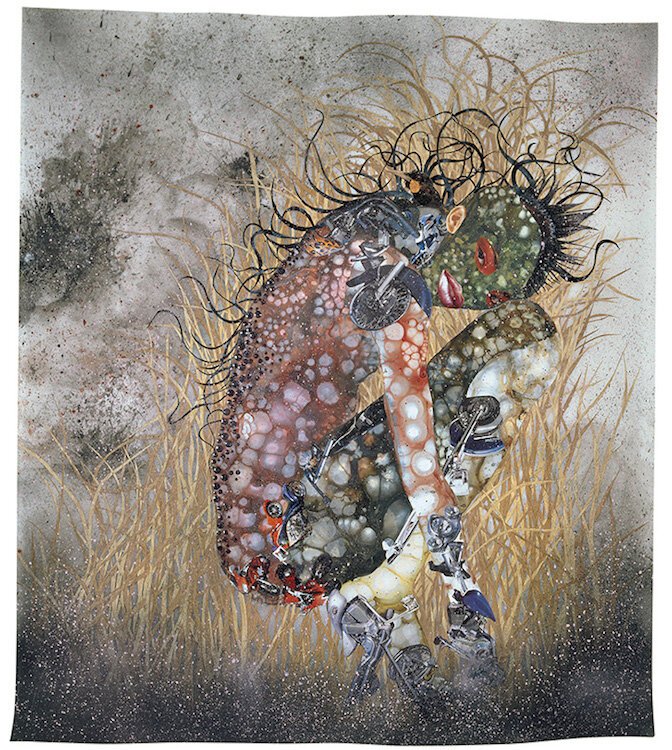

12 weeks. 200 pieces of art. Nearly 40 events. Participation by more than 25 community organizations. As the KIA brings in the touring exhibit from The Studio Museum in Harlem, Black Refractions, and two related exhibits the community celebrates what we have in common.

It’s not common for art museums to take down most of their pieces to make room for an exhibition (or three).

It’s unheard of for a museum to put most of their permanent exhibits in storage to refill its spaces with African American art.

“We are the only ones that we know of, the only significant American art museum, that’s deinstalled its entire permanent collection to do shows by African American artists,” Kalamazoo Institute of Arts executive director Belinda Tate says.

The touring exhibit from The Studio Museum in Harlem, Black Refractions, will make its only Midwest stop, bringing 91 works spanning nearly 100 years to the KIA. Two other exhibits, Where We Stand: Black Artists in Southwest Michigan and Resilience: African American Artists as Agents of Change, will add up to a total of over 200 works. It’ll be a “12-week celebration,” Tate says, starting Sept. 14.

Visitors will see “a very broad perspective of the myriad stories told by these artists. Hopefully, they’ll see that they’re also telling stories that connect us through our common humanity,” Tate says.

Connecting local communities with art

Could it be that some people have a preconception that art museums are full of works that are Eurocentric and old, or abstract and abstruse, that don’t reflect their lives in 21st century America?

Ask Tate that, and she’ll take you to the KIA’s traditional gallery of pre-1915 work. She points out their Edmonia Lewis 1872 marble sculpture, “Marriage of Hiawatha”, which depicts Native Americans in Greco-Roman form. A Native/African-American, Lewis was “one of the few women of color working in marble in the 19th century.”

A few steps away is “Heart of the Andes,” an 1871 landscape by Robert Seldon Duncanson. In an imagining of a mountainous Andes, seven years after the U.S. Civil War, Duncanson included Union soldiers, the U.S. flag, and a rainbow from dark clouds. “He’s very optimistic about a bright future in America where there’s more freedom for everyone in this vast landscape,” Tate says.

In another room hang works that will be in Resilience, the exhibit of art from the KIA collection commenting on social justice and multicultural contemporary life, like Russel Gordon’s “There’s Peace in Unity” and Ulysses Marshal’s “Displaced People.”

Tate points out the diversity in the KIA’s permanent exhibits and invites people to find their own connections. “We have such a rich texture to American history, and we tend to think of things as very linear and very concrete, everything fitting into nice neat little boxes, and that really isn’t the case.”

She began working on the temporary transformation two years ago. The work included contacting community organizations, from Western Michigan University to the Black Arts and Cultural Center, to see if they’d like to be involved. When “representatives from 25 different organizations show up to say ‘yes,’ that’s pretty special,” she says.

One of the two curators of Where We Stand, Fari Nzinga, says that they’ve been meeting with organizations that work in the education, art and cultural space, and that “are specifically working with black and African American communities, trying to offer this exhibition as a way to say, ‘Hey, how can we signal-boost whatever you’re doing, or how can we offer this as a space of collaborative effort?'”

The museum has been doing more than just promoting the event, she says — they wish to connect art with communities who might not think the KIA has art that could connect with their lives. “We’re coming up with not just how can we communicate what this is to people, but how do we create an opportunity for different constituents to make meaning out of this exhibition,” Nzinga says.

Branches of the Kalamazoo Public Library, Kalamazoo College, KVCC and WMU, and the Black Arts and Cultural Center will hold panel discussions and other events throughout the months. “They are really going to help us leverage meaningful conversations in circles of the community that we don’t have access to on a consistent basis,” Nzinga says.

“I think there is something really compelling about the three exhibitions that will draw people in,” Tate says. “It will be very difficult to not find something here that you will connect with.”

What most excites Tate is seeing “the community unite to celebrate art. That’s huge, we don’t often have those moments we can come together and celebrate lots of things, but to have art at the center of the conversation about what’s happening in Kalamazoo this fall — Yes! That’s exciting!”

She continues, “And I’m also excited about the fact that that celebration is focused on black artists, artists who have felt overlooked and marginalized and faced huge obstacles — I mean, it’s a challenge being an artist for anyone! That is hard work.”

It’s “huge,” Tate says, “for this community to say, we’re committed to diversity, equity, access and inclusion, and that this is an important learning moment for us, and we’re going to take advantage of it, and we’re going to support it in a big way. That’s huge for any community, and for me that makes Kalamazoo stand out in a way that I just haven’t seen or witnessed.”

Where They Stand: Three Kalamazoo Artists in Where We Stand

MARIA SCOTT leaves it up to the viewer.

Scott doesn’t title her abstract ceramics. They have meaning to her — but she won’t talk about their meaning. “I don’t like to lead people’s thoughts,” she says.

But she’ll talk at length about the struggles and extremes she goes through to create her art.

Most of what she makes go through “literal flames.” The day she spoke, she was planning on pit-firing — the ancient art of finishing pottery in a pit of blazing material — a new piece later in the day. “We’ll see what happens… it could just split in half.”

Two Scott pieces for “Where We Stand” were set aside in a basement room at the KIA. One, a stoneware bowl, she’d fired in a kiln. Then, “I put it in a barrel filled with sawdust and straw, and I set it on fire.” She let it smolder overnight giving it smoky marks. She then placed a ring of sticks from a dead tree in her yard and a ring of rock salt in it. The process was difficult — “I could only blame myself for that agony.”

Scott with piece that had been fired to 1,500 degrees then placed in sawdust. ”I singed some hair off with this one. It’s pretty intense.”

Scott with piece that had been fired to 1,500 degrees then placed in sawdust. ”I singed some hair off with this one. It’s pretty intense.”

Next was a hollow, domed, flat-black vessel. It had been fired in a kiln at 1,500 degrees, then quickly placed in sawdust. “And it basically just burst into flame. And then I throw some sawdust on top of it, and there’s just fire. And then we cover it. And that’s why it’s black.”

All ceramics go through extreme heat, she points out. But she puts hers through extra extreme steps. “These pieces go through a lot of shock, which is why I’m never finished until that last firing.”

She touches the hollow vessel. “I singed some hair off with this one. It’s pretty intense.” Scott sighs heavily. “I’m not ready to do that process again for a while. But I was really happy with the outcome. This piece, I wanted it to be black. It came out exactly as I envisioned it.”

Scott grew up in Chicago, started drawing as a girl, and worked with clay in high school. At 18 she went to Siena Heights University, then moved to Kalamazoo in 1984. She worked in the print field, while also creating her ceramics.

She understands that abstract art like hers might be intimidating to some. “People tend to be afraid of art and think that they need to understand art, so they don’t want to come in (to the museum). I like to tell people that you don’t need to worry about that. If you like it, you like it. If you don’t like it, you don’t like it. There’s not going to be a quiz at the end of your visit. Don’t worry about understanding something. Just look at it and take it for what it is.”

TANISHA PYRON is on a mission to reclaim her image.

She’s an actress, writer, poet, filmmaker, but her work that will be on the walls for “Where We Stand” will be her self-portrait photography.

Pyron’s photos may show her as a black Wonder Woman, or as a steely ’50s mother with hair in curlers and cigarette sardonically drooping from her mouth, or as an “Afrocentric Pin-Up Girl”. For Where We Stand, she’ll display collage art that mixes her photos with vintage record album covers.

She spent much of her childhood in smalltown West Michigan, then later in Saginaw. Pyron had often been subjected to others’ standards of beauty. “The things you hear as a child — ‘oh, you have a big nose!’ or ‘anyone ever tell you that…’ No, no one told me and I didn’t even ask you!” she says with a laugh in her Vine neighborhood home.

“I don’t think anyone is exempt from that sort of scrutiny of your humanity, especially when you’re younger. We’re all put in these boxes of what we should be,” she says. “Even when people are well-meaning…. I have a big afro, and my mom to this day, if I wear my hair out, she’ll say ‘oh, it’d look so pretty if it was straight.’ I haven’t straightened it in 20 years, mom, I’m not gonna do it!”

Photographer Tanisha Pyron. ”What I wanted to do was take that girl off the auction block, to take myself, my beauty, my aesthetic, and take it out of the hands of others.”

Photographer Tanisha Pyron. ”What I wanted to do was take that girl off the auction block, to take myself, my beauty, my aesthetic, and take it out of the hands of others.”

She came to Kalamazoo to become “a Western theater girl.” Pyron then went on to the University of Illinois to earn her masters in theater. There, a head-shot session with a photographer friend turned into creative art photos among “old pottery behind the art building.”

Creatively manipulating her image before the camera inspired her to buy a $1,200 Canon Rebel. “It was self-acceptance in a regard, because I saw myself in a way that I hadn’t before.”

Pyron returned to Kalamazoo where she co-founded Face Off Theatre, was active on the stage, wrote, and shot her “confessional self portraits.” Her photography was a hit on national black culture site Afropunk.

She estimates that 40,000 people follow her online, and she’s been told that “three-quarters of a million people saw my art (on Afropunk) over the course of seven days. You couldn’t tell that from looking at my shoes, because they’re not $300 shoes.” Many have seen her work, but that hasn’t lead to a steady income. “Most of my work has been featured in predominately-black spaces.”

For Where We Stand, Pyron will also have one of her short films on a loop in the gallery, will perform poetry for the Sept 14 exhibit opening and hold talks Oct. 28-Nov. 1 at the KPL’s Washington Square branch.

Pyron says she’s working on her brand, but it’s a brand with a mission. “I think America’s made a lot of assumptions about the depictions of black women — we could go all the way back to minstrel show archetypes and some of these very specific ideas like the ‘welfare queen,’ to the ‘hood rat,’ all of these words that in-frame and encompass how others talk about black womanhood, and what I wanted to do was take that girl off the auction block, to take myself, my beauty, my aesthetic, and take it out of the hands of others.”

She adds, “I love being black and American,” but Pyron wants to redefine black Americana as a genre, to “imbed in that both the beauty and the pain, and take it out of that place of archetypes and caricatures, and make it nuanced.”

BRENT HARRIS knows where he stands.

It’s tempting for a journalist to turn the title of the exhibit into a question: Where do we stand with African-American artists in Kalamazoo?

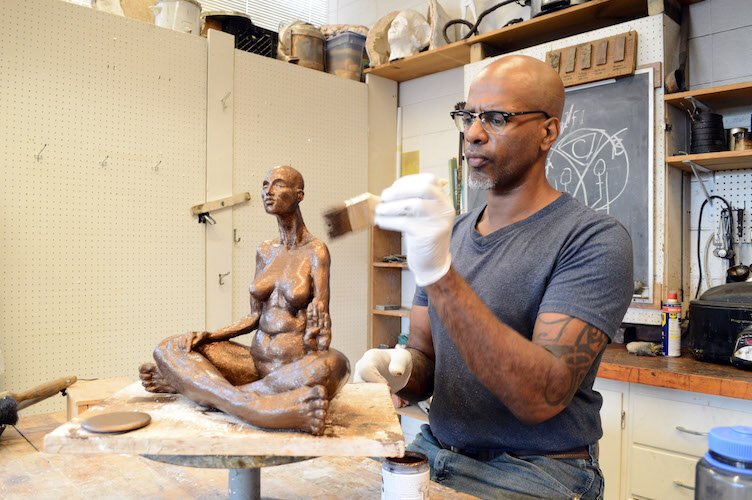

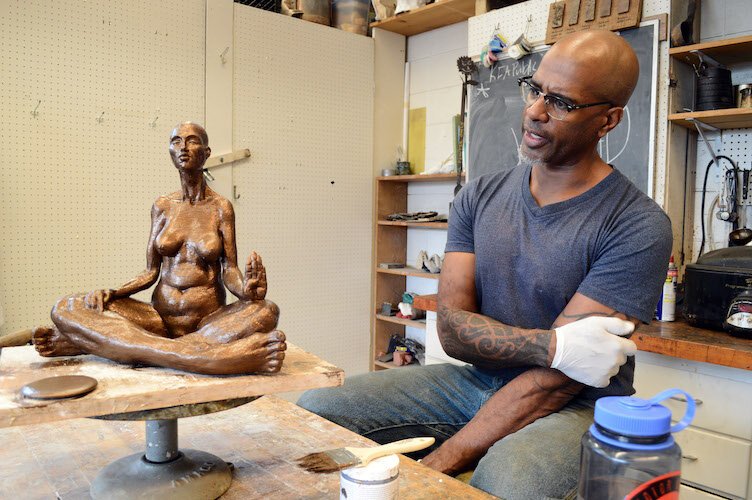

While brushing bronze patina on a meditating figure in his KIA studio, the sculptor thinks for a moment.

“It’s an ambiguous title, but Where We Stand can also be a declarative statement. It’s not up to you where we stand, we can make the decision ourselves. I think the ambiguity about us as black artists having to be defined by the European standard of art has always been problematic because it denies the inherent aesthetic and cultural story behind our work in favor of another,” Harris says

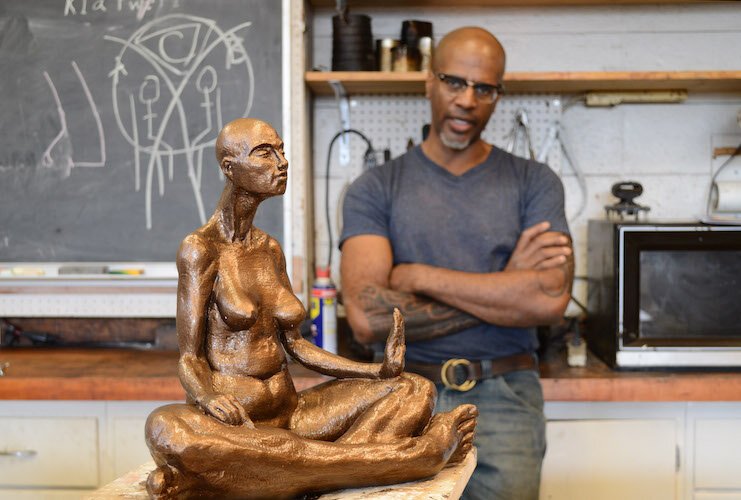

Sculptor Brent Harris. ”The body is like the alphabet, and I’m just sort of expanding it, pulling it, contracting it.”

Sculptor Brent Harris. ”The body is like the alphabet, and I’m just sort of expanding it, pulling it, contracting it.”

“Having a show like this is very important because the narratives are starting to change, the cultural stories are changing, and we need to replace them with more-historically and culturally accurate stories that reflect everything.”

He was born in Flint, grew up on the “rural side of Ypsilanti.” Harris came to WMU in 1988 to study psychology, which led him to art therapy, and then art itself. He ended up with a BFA in sculpture in 1994.

Harris was tired of the academic world and “wanted to be of use,” so he became a paramedic. He found himself working on figures in the back of the ambulance, so he began doing castings at the Alchemist TYE studio.

He became co-owner of what became the Alchemist Sculpture Foundry, and for 15 years “we did some pretty amazing stuff,” Harris says.

“The markets changed, the art world changed,” so the shop was closed in December. Luckily, the KIA art school hired him as sculpture department head.

His is a “mannerist style. I like to take the form and exaggerate it. I also use the form for storytelling.” For Harris, work on a figure is like working with words; “when poets can use the language to get a little bit more floral and play with the words…. The body is like the alphabet, and I’m just sort of expanding it, pulling it, contracting it.”

The meditating figure he was working on is a smaller version of the yet-to-be titled piece he’ll have in the show. “She’s grounded, so the emphasis is on the lower body, the legs, so everything is really heavy in proportion. And you can see elevation because it pulls upward.” The meditating woman’s head is reaching upwards.

Harris is also working on “Death Mothers,” female figures with bird skulls for heads, and other, male figures sprouting seed pods from their necks.

He’s also created more-traditional work, like the bust memorializing slain Kalamazoo Public Safety Officer Eric Zapata, erected on the Kalamazoo Mall, and a few other public sculptures.

Harris doesn’t focus on race or culture in his art. “Whether it’s African American or black is not a consideration. It’s where I come from.”

What does Harris think of the entirety of the KIA being filled with work by African American artists?

“I’m absolutely blown away by this, just as a civilian, to see all this work coming here. Like a kid in a candy store,” he says.

“It’s like when I saw ‘Black Panther’ for the first time — movies now being made by black writers, just telling a story without having to always consider the white perspective…. My heart just breaks open — Ahh! I’ve been waiting my whole life for this! You don’t realize how small your steps have been, your whole life, the tiny little box you live in until you start feeling, ‘oh god, now I can see that story.'”

As a “civilian,” an art fan, Harris is excited to see more more-diverse stories. “I can see perspectives I’ve never seen before. It just makes the world better.”