Tribal Officers go undercover to combat human trafficking along I-94 corridor

The Nottawaseppi Band of the Huron Potawatomi received a $900,000 federal grant to combat human trafficking in Indian Country through undercover operations, victim-centered interventions, and collaborative efforts with local law enforcement along Michigan’s I-94 corridor.

Editor’s note: This story is part of Southwest Michigan Second Wave’sOn the Ground Calhoun County series. All photos in this story are courtesy.

Human trafficking laws in the United States were first written in 2000, and funding to assist with enforcing those laws is finally catching up, says Homer Mandoka, Tribal Council Chairperson of the Nottawaseppi Band of the Huron Potawatomi.

Prior to 2000, the Department of Justice (DOJ) filed human trafficking cases under several federal statutes related to involuntary servitude and slavery, but the criminal laws were narrow and patchwork. In the last two decades, Congress has passed several comprehensive bills designed to bring the full power and attention of the federal government to the fight against human trafficking.

In December, Chris Mandoka, NHBP Tribal Police Chief (no relation to Homer Mandoka), announced that his police department had received a $900,000 six-year grant from the United States Justice Department to focus on human trafficking prevention and awareness efforts to address the underreported issue of human trafficking in and around Indian Country.

In addition to a focus on law enforcement intervention, the undercover officer will work with local tribal partners to ensure cases are handled with cultural sensitivity, emphasizing a trauma-informed approach.

That undercover officer is a Tribal member. Originally from Tennessee, she worked for the Battle Creek Police Department for two years in an undercover capacity before coming to work for the NHBP Tribal Police in 2024. During this time, at Chief Mandoka’s urging, she also worked with SWET (Southwest Michigan Enforcement Team), a multi-jurisdictional narcotics task force operating in Southwest Michigan, focused on investigating and reducing the trafficking of illegal drugs, such as methamphetamine, heroin, and fentanyl, as well as associated violent crimes.

“When she worked here, she was a rock star, and I put her in SWET in May 2025, where she has done a fantastic job. We didn’t really have a presence there,” Chief Mandoka says. “I knew people were bringing drugs into the (Pine Creek Reservation) reservation. When we were formally notified of the grant in November, I called her to see if she’d be willing to do more work.”

Her work with SWET was a way to bridge the gap between NHBP Tribal Police and Michigan State Police, with the Tribe paying her wages. Chief Mandoka says she will continue her undercover work for the next six months and is expected to come out in November or December “as the face of what this can be”.

“Ultimately, I said we need successful prosecutions,” Homer Mandoka says. “That has to be the cornerstone, and for that to happen, we need to identify best practices so law enforcement can improve their skill set and mindset.”

In addition to covering the salary for this full-time officer, the grant is being used to pay for equipment and conferences, including one at the Casino that is being planned for June or July that will bring in Federal law enforcement officials and other subject matter experts. Despite having good working relationships with police departments in jurisdictions throughout Calhoun County, Mandoka says Tribal police departments aren’t always seen as equals.

”Native Americans are typically miscategorized in government records and police reports,” he says.

Through checking the records of one local police department, he found that out of 56 contacts, 53 were coded incorrectly.

”We need to make sure that we have correct data and more training for hotels along the I-94 corridor,” he says. “Human trafficking is not people trapped in a shipping container.”

Leaders of local organizations say it can happen anywhere, including rest stops or in someone’s home.

The absence of accurate data collection presents challenges for Mandoka’s department when they’re trying to contact Native American women who are victims. He says the suspects represent very diverse categories.

“Among the most distressing factors is that almost all of these victims had kids. They are in a hopeless cycle, and it’s very difficult to get out of it,” Mandoka says. “They all have sought services through NHBP’s Victim Services. What happens if the woman shows up and she has a kid? What if she’s got felony warrants or is suffering from withdrawals? The bad guy is arrested and doesn’t have problems like this.”

Adding to this is the way each law enforcement agency deals with these cases.

The grant and NHBP officers’ work on anti- human trafficking efforts is targeted at any victims and suspects within its jurisdiction.

Because the majority of Indigenous individuals don’t reside on a reservation, Mandoka says this complicates tribal-nontribal member interactions.

“Policing in Indian Country is complex. This highlights the relationships that tribal nations have with local area governments,” he says. “I am glad to report that the area agencies around NHBP have been overwhelmingly supportive.”

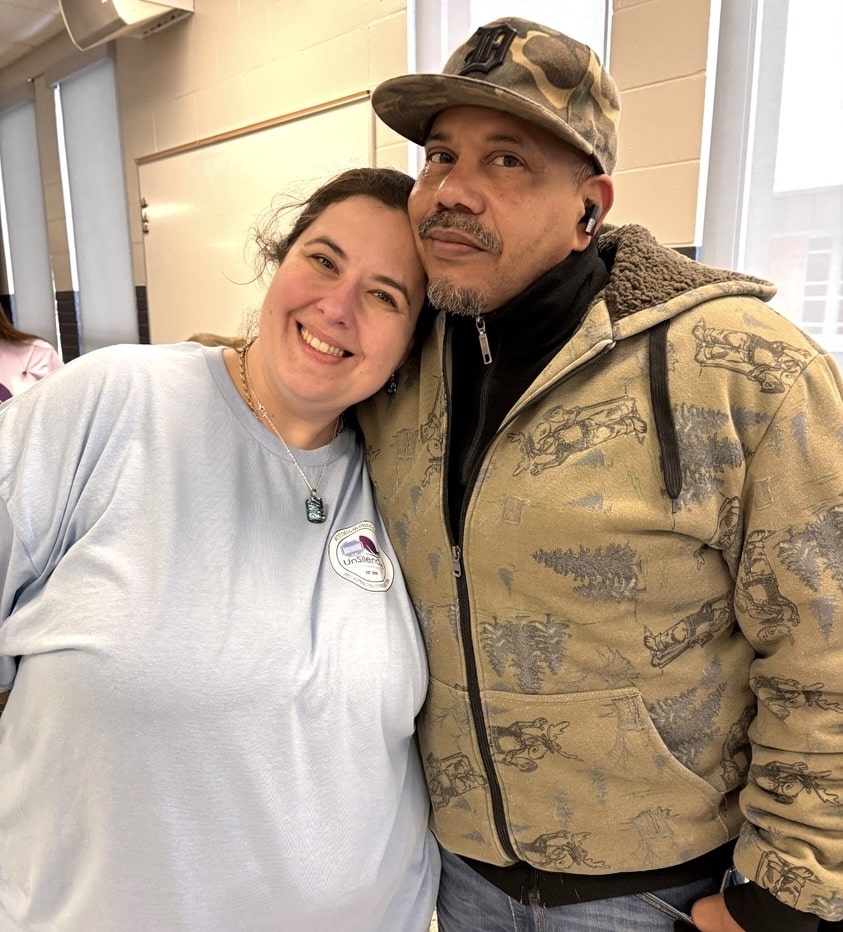

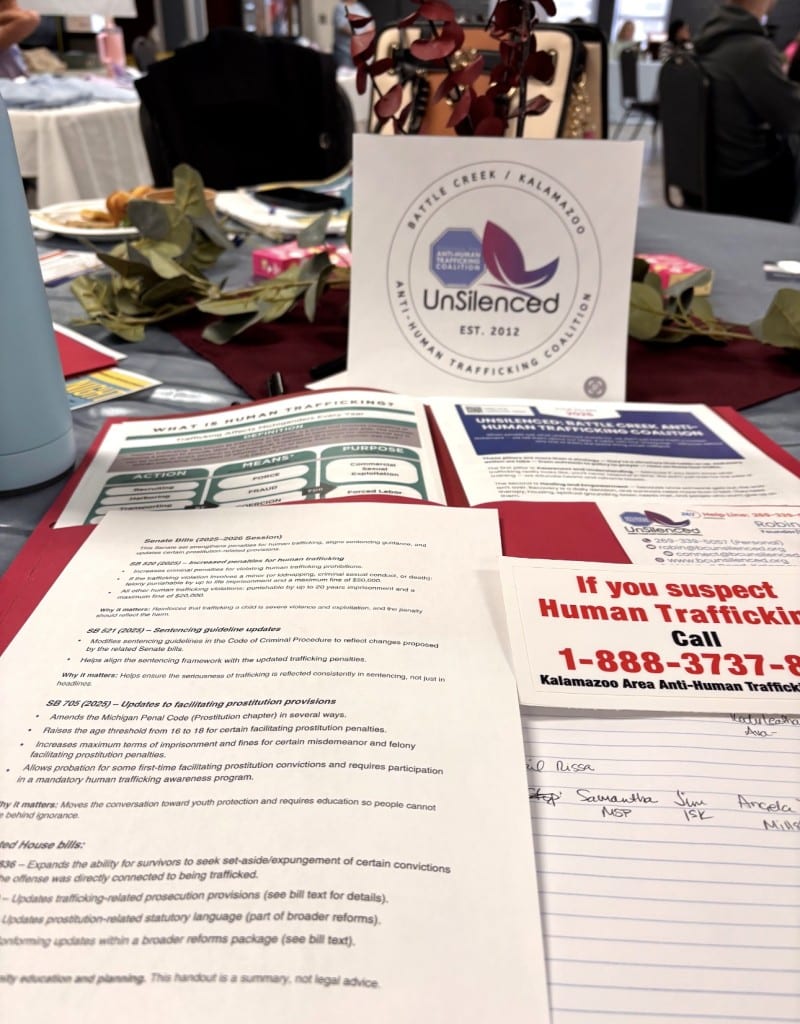

Mandoka is wasting no time in making connections, including one with Robin Bolz, a survivor of human trafficking who is the Founder and Director of Operations for Battle Creek UnSilenced Anti-Human Trafficking Coalition. On January 31, representatives with NHBP and its Tribal Police department were among more than 60 survivors, community members, and frontline professionals who gathered at the Comstock Community Center for “Shine A Light UnSilenced Community Awareness Day.”

When the Chief Mandoka and Bolz met prior to the January event, Bolz says, “We talked about what his victim-centered approach is to help survivors and treat them like they’re not criminals and get them the resources that they need. When they do sting operations, one of the things we would do is meet with their team and connect them with someone to network resources and help with the aftercare of the victim to make sure they feel heard, understood, and accepted.”

During the past 18 months, the NHBP Tribal Police has conducted at least five successful sting operations along the I-94 corridor near FireKeepers Casino.

”The big push was for women to be treated as victims. We changed it so we would have Victims’ Services with us so there would be immediate access to a counselor or victim advocate right there in the hotel room with them,” Chief Mandoka says. “This gives a victim an immediate different perspective to show that they have different options in life.”

Most of the victims are dealing with substance use and alcohol issues, as are their male abusers, some of whom are also sexual deviants, Mandoka says.

”If they show up with equipment, the victim’s going to have a bad night,” he says.

As a teenager, Bolz was the victim of men who trafficked her. While they didn’t use the equipment that Mandoka talks about, they did control her by withholding food and affection. She says this is a common practice, and women acquiesce to their abusers because they have substance use issues, don’t have money, and may have children to support.

Speaking as a victim, she says, victims don’t think they can do any better.

”Some are exchanging sex for the meeting of basic needs,” Bolz says. “It’s not what they want, but it’s the only way they know how to do it.”

Prostitution almost always involves human trafficking because the individual is working for a pimp and is not there of their own volition, says Dave Gilbert, Calhoun County Prosecutor.

“I once had a case where a husband was bringing his wife from Grand Rapids and pimping her at a local hotel for a number of years,” Gilbert says. “Sometimes people don’t understand that they’re not free to leave or they have children to think about.”

He says FireKeepers Hotel, which is attached to the Casino, is not an anomaly when it comes to this type of activity.

”It can happen at any hotel,” he says.

While researching online advertisements for sex, Mandoka came across a business called Spotlight, which has a web crawling service that scrolls through online personal ads focused on sex for money.

”When I began to check Spotlight, I was quite surprised that so many of these ads had our business establishment named,” Mandoka says.

Time to act

During an annual meeting with the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Western District and Michigan’s 12 Tribes to troubleshoot and discuss issues of concern, Homer Mandoka, a former police officer in Bronson, says Human Trafficking was brought up.

“Because of the new Federal law, we were looking at how we could use that locally. For our tribe and the greater community of Indian country, and myself being a former law enforcement, we recognized the jurisdictional gaps between the Feds, state, county, and local law enforcement and the Tribes,” he says. “There were gaps to be resolved if it happened on our site. This is an important topic for the Tribal community to protect and preserve Indian Country rights.”

The anti-human trafficking work began to take shape after NHBP leaders gathered with the FBI (Federal Bureau of Investigation) and the ATF (Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms) and victim service coordinators. Collectively, the point was made that crimes like this may fall into a jurisdiction that wants to do something about it right away, but may not have the resources to do that.

”We’ve seen the consequences of what happened with prior crimes in Indian Country,” Homer Mandoka says.

Over the years, he says, there has been a natural progression of Congressional legislation, including the Murdered Missing Indigenous People (MMIP) Act, which was enacted in 2020, that has eliminated the confusion regarding jurisdictions.

“If you don’t have officers trained to respond in certain ways to investigate crimes, little gaps become big gaps,” Homer Mandoka says.

Surprise leads to commitment

The subject of Human Trafficking was the focus of a Master’s thesis that Chief Mandoka wrote. What he saw as a deputy with the Calhoun County Sheriff’s Department made it real.

He was involved with a child predator investigation about four years ago that was “wildly successful” and showed him how prevalent the incidents were of predators seeking to have sex with minors.

Then he orchestrated a similar effort targeted at children living within the NHBP’s Pine Creek Reservation.

“The goal was to do our own. Something that had never been done in the state,” Chief Mandoka says. “While this was going on, I’d gone to a couple of classes and learned from a similar operation the Eaton County Sheriff’s Department ran two years ago that there were all these people trying to have sex with minors.”

Soon after, the focus pivoted to adults who were being victimized.

He learned of the grant opportunity from the Chief of Police for the Match-E-Be-Nash-She-Wish Band of Pottawatomi Indians (Gun Lake Tribe), which operates the Gun Lake Casino Resort in Wayland. They had earlier applied for and received a similar grant.

Bolz says she appreciates the NHBP’s focus on anti-human trafficking efforts.

“Nailing this down and making tougher punishments for criminals will definitely lead us towards changes in legislation and increase awareness of how this happens,” she says. “The grant money will allow them to go farther, highlight the need, and integrate a lot of collaborations for us all.”

She and Chief Mandoka acknowledge that while the majority of women who are trafficked aren’t doing it by choice, some are doing it by choice.

“We see it every day. It depends on whether or not the victim is ready and willing to accept help. If they’re not ready to disclose who their abuser is, there’s not a lot we can do,” Bolz says. “I put two people in a shelter last month. They stayed for 48 hours and went back to their abusers. When people are still trauma-bonded, there are so many layers. It’s messy, and it’s everywhere. For every one mile you travel in the United States, you pass a trafficker.”

“There needs to be a dedicated effort to combat this because it touches everything else,” Chief Mandoka says. “There’s always a story. Why is this person doing this? You have to sit with the victim at a table and talk about this.”