Tribal Voices Amplified: A new era of representation in Michigan legislative history

Michigan is the first state in the nation to establish a legislative office for official tribal consultation with the establishment of Bill 5600. Tribes will consult on laws regarding issues such as land, water, wildlife, and economic development.

Editor’s note: This story is part of Southwest Michigan Second Wave’s On the Ground Calhoun County series.

The voices of Tribal members in Michigan will be heard by lawmakers in Lansing with the formal passage of House Bill 5600 which ensures that the state’s more than 240,000 Native Americans or Alaska Native residents, more than 622 of whom live in Calhoun County, have a seat at the table when legislation is being crafted.

Michigan is the first state in the nation to establish a legislative office for official tribal consultation with the establishment of the Bill signed by Gov. Gretchen Whitmer on Wednesday.

“I’m very excited that (this Bill) went through and was signed into law,” says Barry Skutt, Chief Executive Officer for the Nottawaseppi Huron Band of the Potawatomi (NHPB). “Our Tribe and Michigan’s 11 other Tribes now have the opportunity to work directly with our state legislators.”

The Bill, which passed on Dec. 12, was introduced by State Rep. Carrie Rheingans (D-Ann Arbor) and established the Office of Tribal Liaison (OTLL). The legislation received bipartisan support from the State House of Representatives which passed it on September 27 along with House Bill 296 which designates September 27 as Michigan Indian Day.

A total of $500,000 is included in the State’s 2025 Budget, which took effect October 1, for the OTLL which will be a two-person operation, Rheingans says.

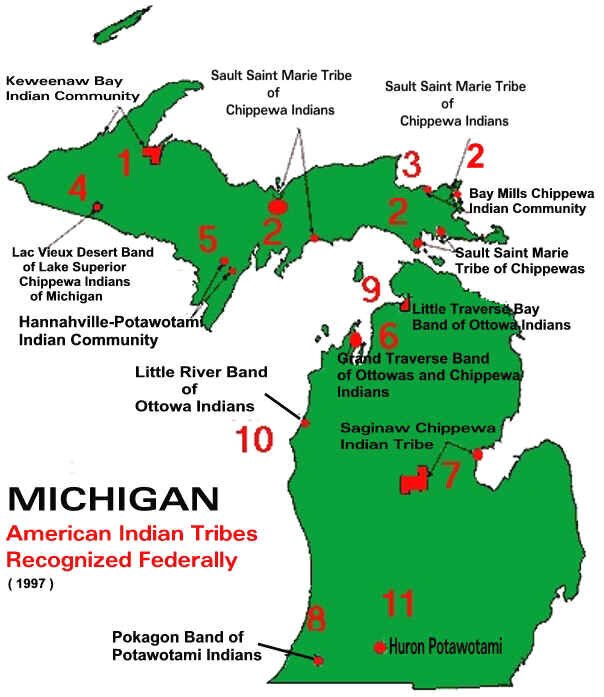

“This first-of-its-kind law creates a point of contact between Tribes and the legislature and will inform the legislature of Tribal issues. The Tribal Legislative Liaison Office is charged with establishing and maintaining a government-to-government relationship between the 12 federally recognized Tribes in Michigan and the legislature,” according to information on the National Caucus of Environmental Legislators (NCEL) website.

“The Office will also consult with the legislature during the development of legislation that affects federally recognized Tribes in Michigan such as land, water, wildlife, and economic development issues.”

Additionally, the Tribal legislative liaison office will also provide at least one hour of training annually to legislators and their staffers on the history and current state of the 12 federally recognized Tribes in the state, as well as how to work with the liaison.

Rheingans says she is “overjoyed to see the OTLL become a reality.”

“The OTLL will help advance cooperation between governments because it will help the Legislature prioritize tribal needs, perspective on legislative impact, and better future collaboration,” she says.

“It will be nice to have somebody who will be able to work on behalf of Michigan’s 12 Tribes with both the House and Senate,” Skutt says. “We just don’t have that ability to have access to whole legislative bodies. To have someone there to represent the 12 Tribes is great.”

Although not Native American, she says she introduced the Bill because it was the right thing to do.

“I believe that anybody who’s going to be affected by a law should be able to have a say in making that law,” Rheingans says. “Tribes should have a say in how laws are written in the first place, not just when they’re implemented. I heard this from tribes.”

The Bill holds significant meaning for the Nottawaseppi Huron Band of the NHBP, said Dorie Rios, NHBP Tribal Council Chairperson, in an earlier On the Ground story.

“It represents a historic opportunity for greater communication and collaboration between the state legislature and Indigenous communities,” she says. “For NHBP members, this liaison office is not just a bureaucratic addition; it symbolizes a recognition of their sovereignty and the importance of their voices in legislative matters that affect their lives. It fosters hope for more inclusive decision-making processes that honor their rights and interests.”

Michigan is home to 12 federally-recognized Tribes. They are sovereign governments that exercise direct jurisdiction over their members and territory and, under some circumstances, over other citizens as well.

“The State of Michigan is obviously a lower-level government than tribal governments which are essentially their own country,” Rheingans says.

The Tribes are members of the United Tribes of Michigan (UTM) a coalition based in Harbor Springs that represents them.

In a letter sent in March to Rheingans, the UTM said that “The Office of Tribal Legislative Liaison would equip Michigan Tribes with the ability to comprehensively voice their formal positions through consultation with the legislative branch concerning legislation affecting Michigan Tribes.”

Gov. Gretchen Whitmer signed an Executive Order (EO) in 2019 that required her office and other state-run departments to have a Tribal Liaison.

“The EO details a process of tribal consultation designed to ensure meaningful and mutually beneficial communication and collaboration between these tribes and the departments and agencies on all matters of shared concern,” according to a press release. “It’s also the first executive directive in Michigan history to require training on tribal-state relations for all state department employees who work on matters that have direct implications for tribes.”

Active participation is a long time coming

Rheingan’s Bill ensures that Tribes are not only represented in state departments but also wherever laws are being written.

The delay in ensuring that the state’s Tribes have a say in legislative crafting can be attributed to various factors, Rios says, “including historical marginalization and systemic barriers that have often sidelined Indigenous voices. Additionally, the complexities of state and tribal governance can complicate collaboration. There may also be a lack of understanding or awareness among legislators about the unique challenges and rights of Tribal nations, contributing to the slow progress in building meaningful partnerships.”

This is exacerbated by a lack of Native Americans serving in Michigan’s House of Representatives and Senate: State

Senator Jeff Irwin (D), a tribal citizen of the Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians, and Rep. Jamie Thompson (R), a member of the Mississaugas of Hiawatha First Nation, are Michigan’s only Native American legislators.

Rios says a multifaceted approach is necessary to encourage more Tribal members to be elected to serve in the state legislature.

She says this includes “creating pathways for political engagement, increasing potential candidates’ access to resources, and fostering community support for Indigenous representation.

“Educational initiatives that raise awareness about the importance of tribal voices in governance can also empower more members to step forward. Moreover, partnerships between tribes and advocacy groups can help amplify the efforts to support and mentor future Tribal leaders in the political arena.”

The OTLL has the potential to expose the state’s Native Americans at a granular level to the inner workers of the political process and the give and take involved in making laws. Having this base of knowledge will increase their confidence and encourage them to seek elected offices or key roles in state government, Rheingans says.

Rios says Rheingans identified several key issues shared by the NHBP regarding the necessity of the OTLL. One primary concern was the lack of representation and consideration of tribal perspectives in state legislation.

“NHBP leaders articulated how many laws and policies have been enacted without adequate consultation with tribal communities, leading to misunderstandings and potential harm to their interests,” she says. “The establishment of the OTLL is seen as a proactive step to address these issues, ensuring that tribal voices are heard and respected in the legislative process.”

The UTM will appoint the Liaison, Rheingans says, adding, “One thing I want to make sure folks understand is that I think the Liaison should be a Tribe member. A lot of people don’t understand that.”

Among the issues this appointee will likely be working on sooner rather than later include the repatriation of Native American human remains; the renaming of state lands that reference historical figures like Gen. George Custer that are offensive and disrespectful to the state’s Native American population; ensuring that pollinators are able to continue to thrive; ensuring that the air, land, and water are safe; and advocating against Line 5.

Rheingans says she established credibility and hard-won trust with Tribal leaders before her work on House Bill 5600 with the passage of another bill she introduced making Manoomin Michigan’s official state native grain. She says Michigan is the first state in the nation to have done this.

The state’s Tribes had been asking for this acknowledgment for many years because “it’s such an important grain and only grows in certain wetlands that are disappearing,” Rheingans says. “They want to keep it going and keep the wetlands clean and nice for grain to grow.”

The passage of House Bill 4852 opened the door for her to begin the conversations that led to the creation of the OTLL.

She admits that there was a steep learning curve involved with both Bills which received bipartisan support, a rarity in the current political climate.

“These Bills that I am pushing demonstrate the need for more Tribal legislation in our legislature. I would love to be even more supportive and I’d like to see more Tribal members run for office because we need their wisdom and representation.”