Editor’s Note: In honor of Native American Heritage Month, we will feature three stories of indigenous women who survived years of trauma at Holy Childhood School of Jesus in Harbor Springs. To address the “troubled legacy of federal Indian Boarding School policies,” the U.S. Dept. of the Interior is sponsoring the Road to Healing Tour as an opportunity for those impacted by boarding school injustices to at long last publicly share their stories. The second story in the series features Sharon Walker Skutt of the Saginaw Chippewa Tribe.

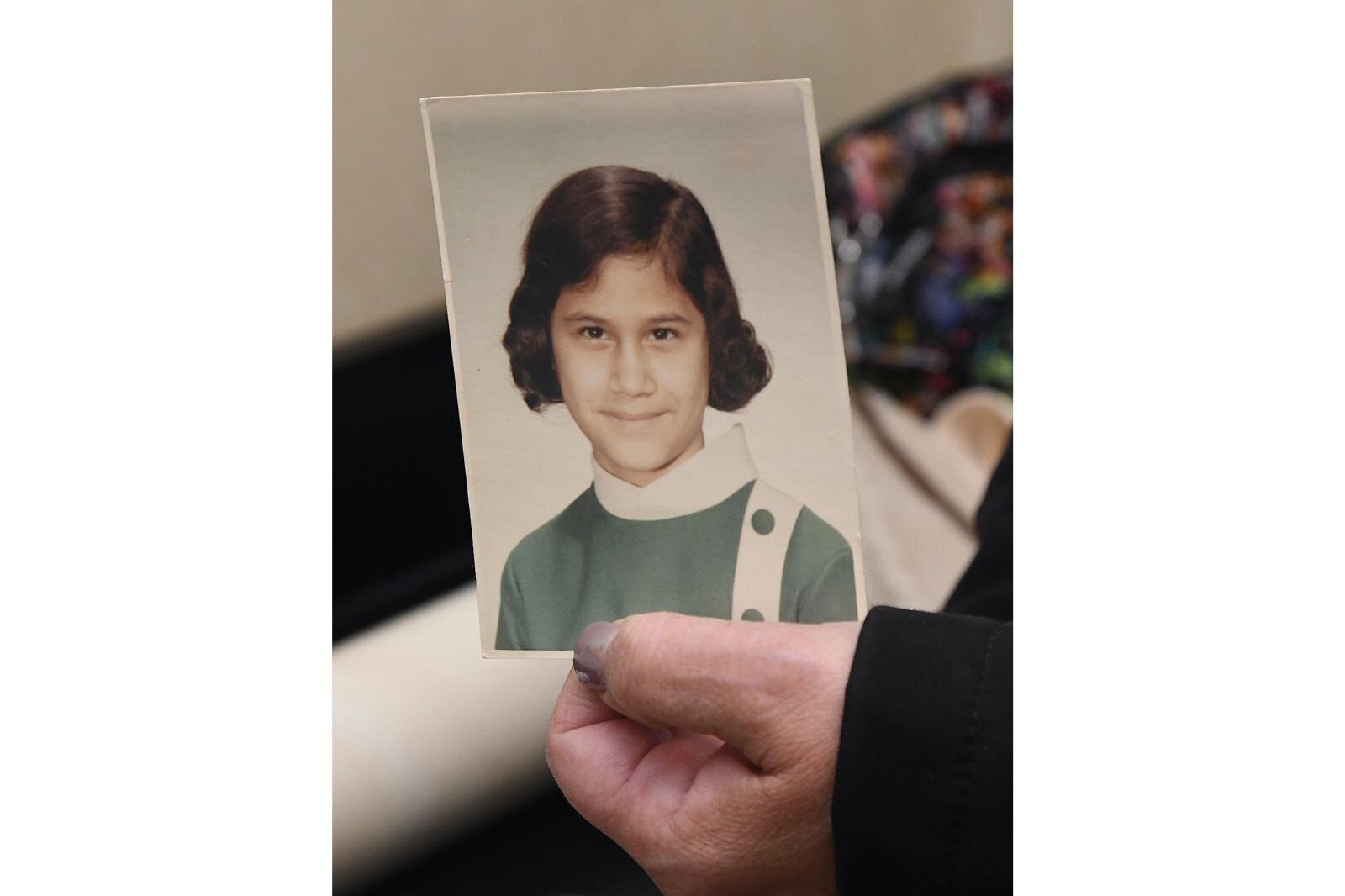

Interlaced with mistreatment at the hands of nuns were small acts of kindness that brought comfort to a young girl during her time at Holy Childhood Boarding School in Harbor Springs.

That girl grew into a woman who is publicly sharing her story as a survivor of that boarding school.

“My mom said I was going to go to a school where there were lots of kids and toys,” says Sharon Walker Skutt, a member of the Saginaw Chippewa Tribe who lives in Midland. “I thought it would be like a Shirley Temple movie. We went up there, pulled in front of the school, sitting inside of the car and it was just a big three-story red brick building, I was like, ‘Where are the kids?’ My mom thought she was sending us someplace good.”

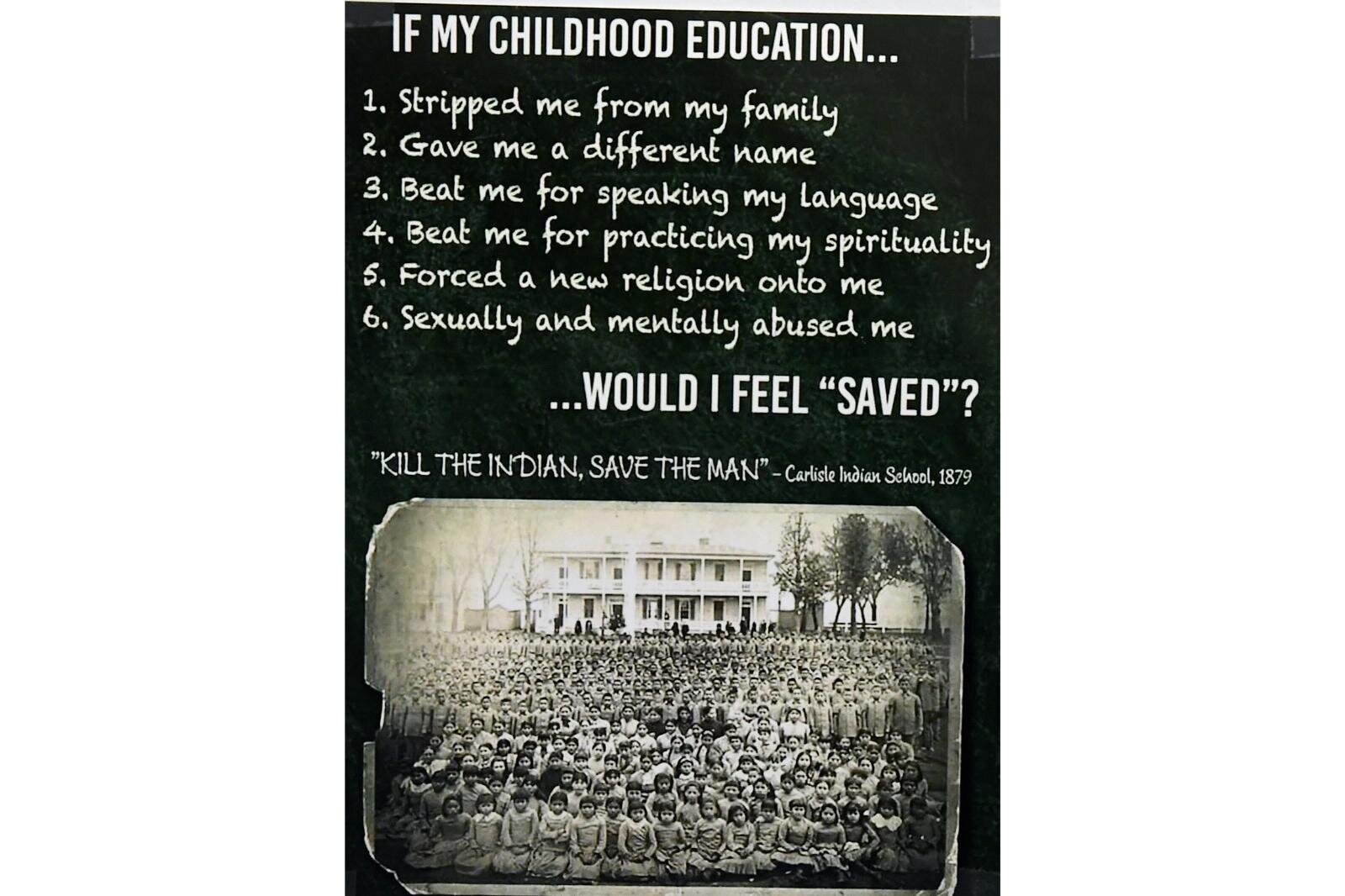

Holy Childhood became the first federally run boarding school in Michigan following “changes in federal policy towards Native Americans such as a push for assimilation, federal funding and the Carlisle Industrial School as a model, Holy Childhood transformed and became like other boarding schools. Even with federal funding, there was still a heavy connection with the Catholic Church, as even postcards drew attention to the Sisters of Notre Dame running the school” according to the University of Michigan’s research on Michigan’s Indian Boarding Schools. The school officially closed in 1983 and the building housing it was demolished in 2007.

Parents, like Skutt’s mother, were told that their children would receive a good education and be fed. What they weren’t told was that their children would be punished for speaking their native language, stripped of their culture, and humiliated for the smallest of infractions. All of this was done as a way to assimilate them into the white man’s world.

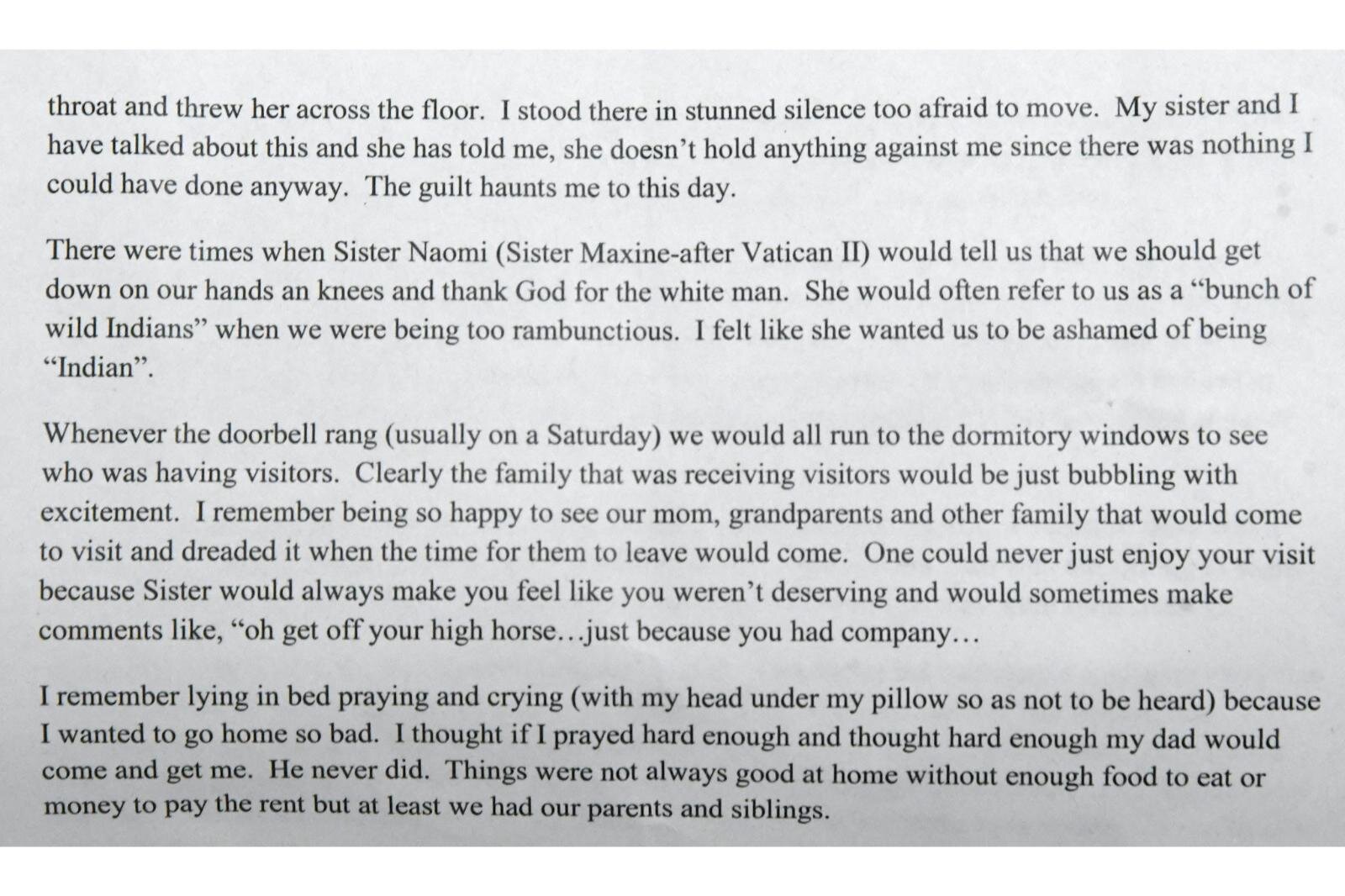

“Sister Naomi said, ‘You should get on your knees and thank God for the white man.’ She said we were nothing but a bunch of wild Indians,” Skutt says.

This is how they were treated.

“We had to wear curlers in our hair every night, but we didn’t have any. Sister Naomi shoved me at a girl and said, ‘Get this girl some curlers or I’ll chop her hair off with an axe.’ I just wanted to go home. That was like the very first day,” Skutt says.

The children at Holy Childhood quickly learned that an air of deference and compliance would be necessary to their survival even if this meant turning away when a sibling was being mentally or physically abused.

As Skutt and others were lining up to go to a church on the school’s campus, her younger sister was walking across a wooden floor with patent leather shoes that were making too much noise as far as the nuns were concerned.

“Sister Naomi grabbed my sister by the throat and threw her across the floor. I just stood there. I was too afraid to do anything,” Skutt says. “I talked to her about this years later and she told me not to feel bad because there wasn’t anything I could have done. The head knows that, but the heart doesn’t.”

Those children who did look out for others and took steps to protect them were met with swift punishment, an effective deterrent in the nuns’ arsenal of tactics to strip away any remaining self-esteem, says Skutt. But, there were the rare moments when covert acts of kindness were successful, one that involved a young boy during a meal in the dining room where students were not allowed to talk.

“We were looked at as these poor little Indian kids who all had to eat whatever was on the table. We were given cottage cheese which I didn’t like,” Skutt says. “I took a mouthful and swallowed it with my milk. Eventually, there was more cottage cheese than milk. A boy sitting next to me slid his milk over to me so I could finish the cottage cheese and I could never forget that.”

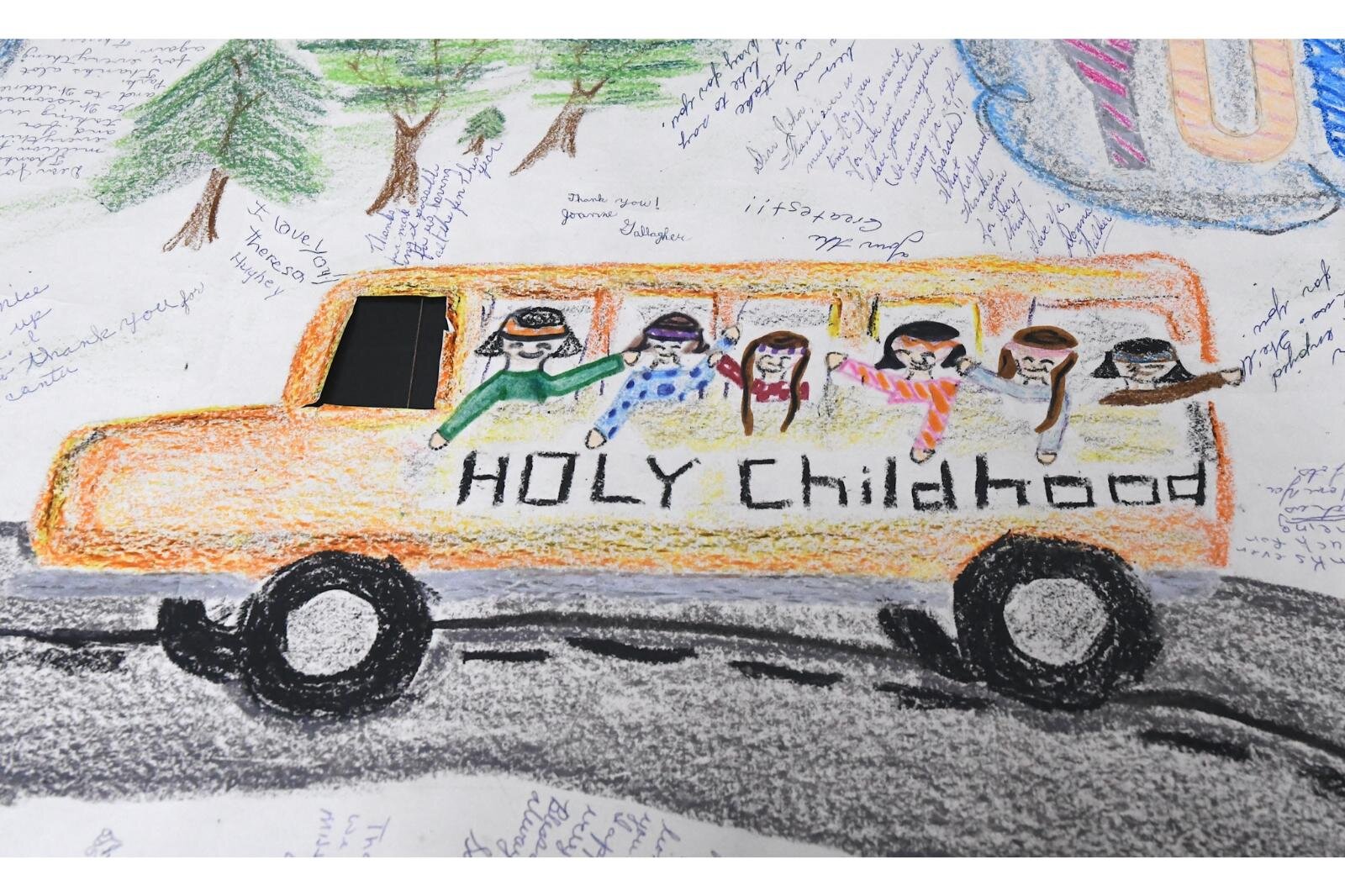

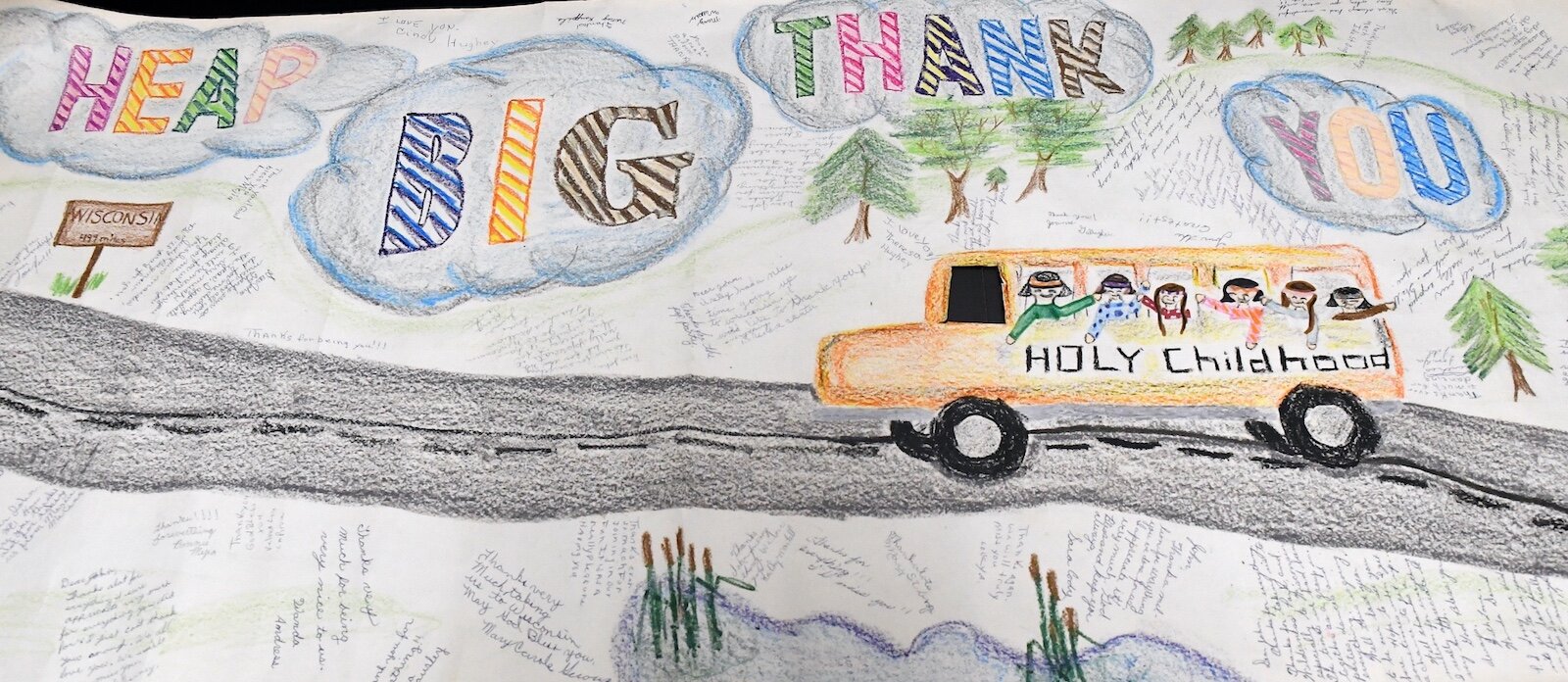

These are the memories that she and three other women who also attended Holy Childhood are sharing publicly with groups and organizations that want to learn about a painful moment in the history of the treatment of Native Americans who lost their culture, their land, and their birthright.

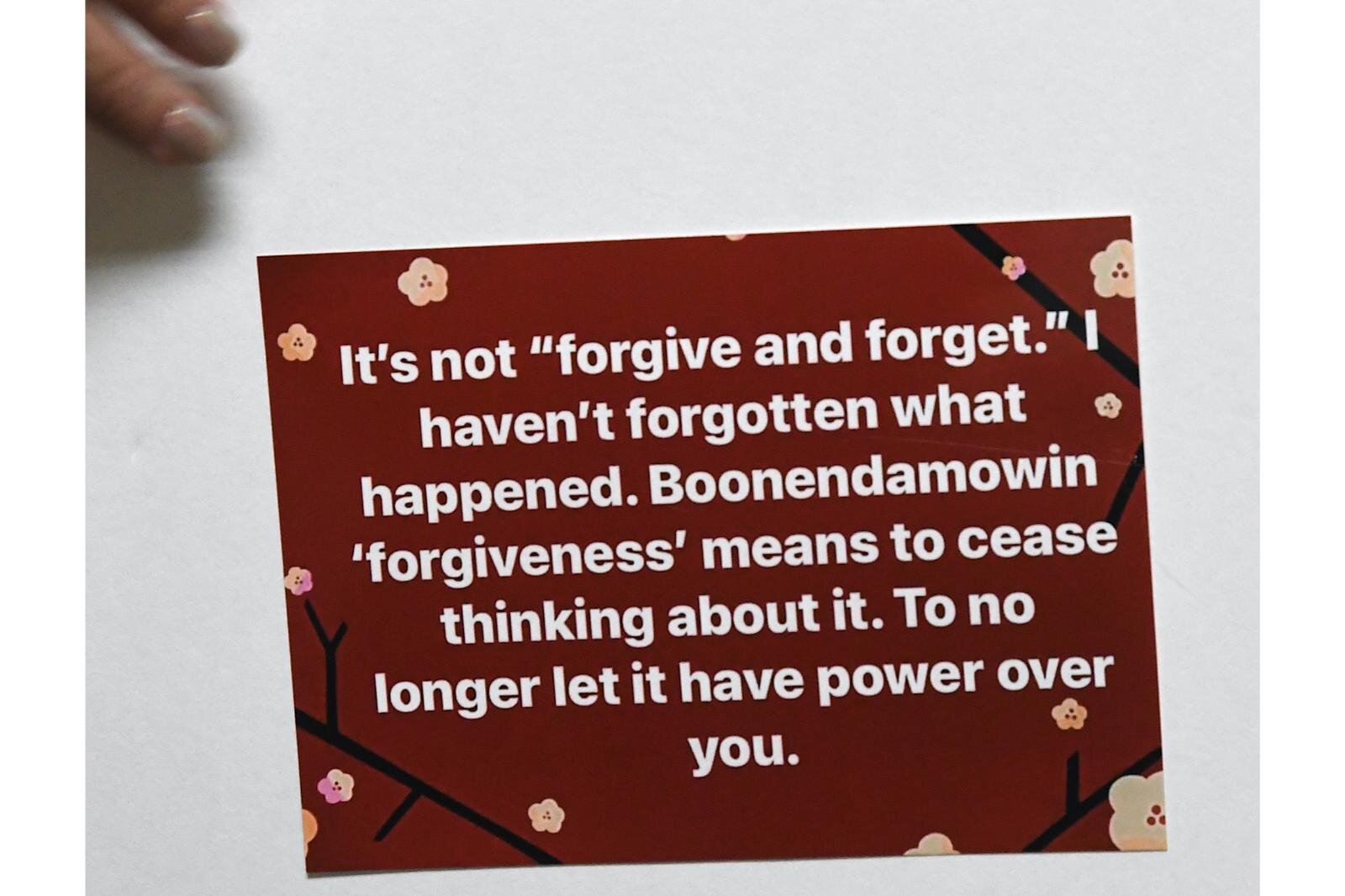

“I say to other survivors, what happened to one of us happened to all of us. We met in Harbor Springs and we bonded together,” Skutt says. “The more I speak about it, the more healing there is. In our family, we didn’t talk about it for many years. We did try to tell my mom when we were adults and she paid attention and she was very sorry.”

Known as the Holy Childhood Survivors, their first opportunity to give voice to the memories they held in silence for so many years happened in August 2022, when they testified in front of U.S. Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland and Assistant Secretary of the Interior for Indian Affairs Bryan Newland. Their testimony came during the second stop on the Road to Healing Tour which was created by Haaland and Newland to “address the troubled legacy of federal Indian boarding school policies” and develop comprehensive reports that “lay the groundwork for the continued work of the Interior Department to address the intergenerational trauma created by historical federal Indian boarding school policies.”

Since their testimony in front of Haaland and Newland, these women have shared their stories with organizations throughout Michigan including the United Tribes of Michigan earlier this Fall. Jamie Stuck, President of the United Tribes of Michigan and Chairperson of the Nottawaseppi Huron Band of the Potawatomi, says their stories are critical to understanding the true extent of the damage these boarding schools did to the children living there, the majority of whom continue to live with those memories.

Skutt has a close connection to the NHBP. Her son, Barry Skutt, is the Chief Executive Officer of the NHBP and like his mother a member of the Saginaw Chippewa Tribe.

Creating an un-holy childhood

Barry Skutt is one of five sons his mother had with his father.

“People always tell me at church what a good job I did as a mom,” Skutt says. “I wanted them to grow up to be productive and they are.”

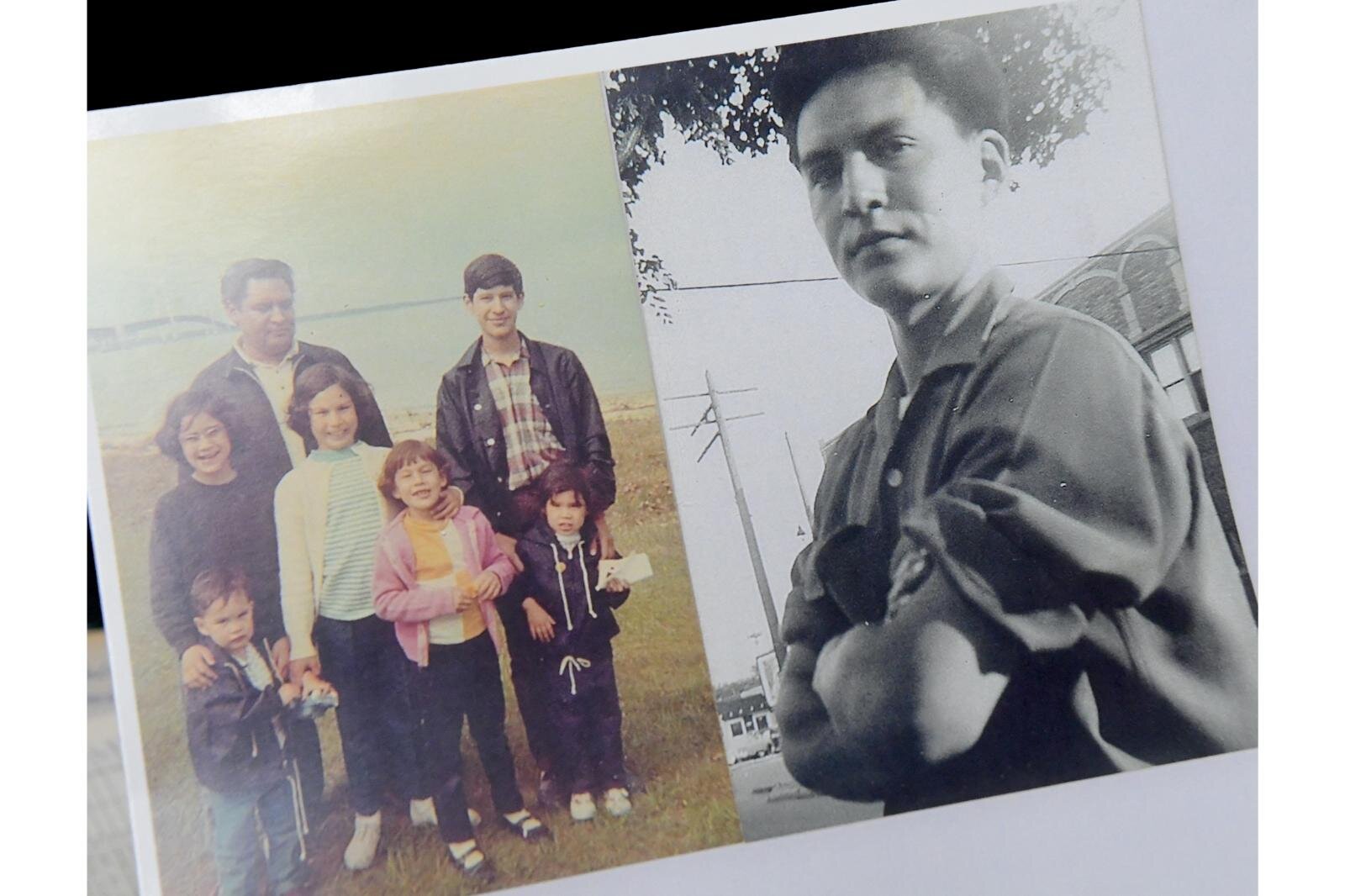

Their lives may have just as easily taken a downward trajectory given the family life their mother had. Her father was an alcoholic and her mother was “struggling” to raise the children. At the time they were living in Detroit.

After a few mental health breakdowns a doctor told her to find someone else to take her children or they would be taken away. Holy Childhood became the only option.

“My dad attended Holy Childhood. The nuns loved him and he had a very different experience than ours,” Skutt says.

Initially, the four oldest siblings went followed eventually by the two youngest. Skutt attended 6th, 7th, and 8th grade there.

Instead of being showered with love and physical affection as many children experience in a typical family, the children at Holy Childhood saw mostly strict discipline and harsh punishment. The majority of them would grow up not knowing how to be good parents because they never had people modeling that behavior.

A nun named Sister Perpetuella was the only authority figure at the school who hugged the children. Skutt says the other nuns, including Sister Naomi, had no mothering instincts in them at all. This was apparent in ways too numerous to count turning times of what should have been fun into terror.

On Halloween, as the children dunked their heads underwater to bob for apples, the nuns would use large powder puffs when they came up for air to coat their wet faces with white powder, says Skutt.

At the end of the school year, as they prepared to leave for summer break, the children had to deep clean their dorms. Sister Naomi, Skutt says, threw a bucket of water across the room because the young girl mopping the floor wasn’t using enough water.

“She would do stuff like that and never apologized for anything.”

While talking about these times is difficult, Skutt says her “heart breaks most” for the men who were at the school as boys, some of whom were sexually abused and were forced to beat each other by the nuns who would watch. She says one of the nuns got pregnant and went on a “sabbatical” for a year returning without a baby.

Skutt says she believes that the nun was impregnated by one of the boys.

“I was literally sick to my stomach. The oldest any of those boys could have been was 13 or 14 years old,” she says. “My older brother won’t talk about his time there. He’s tried to put it all behind him.”

Indigenous boarding schools are often referred to as a place of institutionalized pedophilia because of the sexual abuse that went on there, says the Indigenous Foundation.

“A majority of the children were also beaten and tormented. Some beaten and strapped or tied and shackled to their beds. Needles piercing their tongues or electric shocks were also a recurring punishment for speaking their native language. Statements like ‘Kill the Indian, Save The Man’ or ‘Kill the Indian in Child’ were common slogans that perfectly explain the veracity of the school’s intentions. Indigenous children were not allowed to speak their own language, use their own names, or practice anything of their own religion and culture.”

While at the school, Skutt and her siblings were kept separated from each other and weren’t allowed to talk to each other to process what was happening to them.

This also was a common practice at other boarding schools, according to the Indigenous Foundation.

“Family was not allowed to interact with other family members, for fear they would practice their customs and traditions. The interactions were not allowed for the same reason the children were taken away from their traditional home, to limit their culture.

“Children at the schools grew up without nurturing and loving homes that uplifted them to partake in their culture, leading them to have misconstrued ways of living. Many of them, as adults, lacked parenting skills and utilized tactics of abuse on their children similar to the abuse they experienced within the schools,” according to the Indigenous Foundation. “This has created a perpetuating cycle of domestic abuse within Indigenous homes.”

Some tribes in Michigan, including the NHBP, have offered parenting classes to their members to teach effective parenting skills and break the intergenerational cycle of abuse.

Skutt says she relied on her experiences with her own parents and her time at Holy Childhood to create a different childhood for her children.

“All I knew was that I wanted my kids to feel loved and cared for and that I would never send my kids away,” she says. “The boys all know I went to a boarding school, but I never really sat down and talked with them about it.”

Lifting a cloak of invisibility

The stories of survivors like Skutt are theirs and theirs alone to tell, Stuck says, by way of explaining why he and other Native Americans who could speak to this choose not to.

“No one else should be telling someone else’s story,” he says.

.

Through sharing their stories with Haaland and Newland, the four Holy Childhood survivors encouraged other survivors of Michigan’s boarding schools for Indigenous children to reach out to them. There is a growing private group on social media of about 107 survivors who connect and find support and the understanding only they would know how to provide.

It took Skutt close to 50 years to stop treading through a thick pool of trauma that could have just as easily sucked her into deeper depths. Her children ultimately saved her, she says.

“I had no self-esteem. For years I suffered from anxiety and depression and went to counseling multiple times. I was so depressed and about the time it was the absolute worst was when Barry, my oldest son, was high school age and I knew if I didn’t pull it together I would never see him graduate or get married.”

At the age of 40, she enrolled at Bay Mills Community College and earned an Associate’s degree in Native American Studies. She had a 4.0 GPA all the way through.

“I couldn’t tell my kids to go to college if I don’t go,” she says.

In 1997 she was hired by the Saginaw Chippewa Tribe as a Higher Education Secretary and retired from there in 2013 as their Higher Education Coordinator.

Two years ago, when she was 65, she says she knew it was time to make her story visible because she didn’t want anyone to forget.

The speaking engagements can be tough to get through.

“Every so often the trauma rears its ugly head, but I push through because I know if I don’t people will never know what really happened. In my own tribe, there are people who don’t know we have members who were in these boarding schools. There was one council member who thought this all ended in the 1930s. A lot of people are under that misperception,” Skutt says.

“I would like people to know there are survivors out there and it’s taken over 50 years for them to be able to talk about these things — (there are) so many to talk about.”