Editor’s Note: All photos were taken by Second Wave Photographer Fran Dwight, unless otherwise noted.

KALAMAZOO, MI — The State Theatre is so 20th Century.

It had brought entertainment to Kalamazoo since 1927.

It was designed to be a movie and vaudeville palace when movies were still silent and live shows featured a variety of performers.

A few nickels got a family a night of entertainment at the State during the Great Depression. When the country was at war against fascism overseas, it showed classic monster movies to kids in the 1940s. It survived by showing movies and live acts through the TV era. From the ’80s through 2024, when it closed, the State depended on bands and comedians.

Ask anyone in Kalamazoo their favorite State experience, and you’ll have answers as varied as the decades’ cultures, as varied as our community.

The space inside is still stunning, designed by Austro-Hungarian immigrant John Eberson as a “Spanish courtyard.” Lighting effects created sunsets, clouds, stars, all high in the “sky” above the seats.

The Carmichaels, new owners of the historic theatre, turned the stars back on when Second Wave visited. They have high hopes to bring it back to life for the next 100 years.

The State has been closed since November 2024. In September, Dan and Holly Carmichael, a couple from Sturgis who now live in Texas Corners, purchased the State, as well as Harvey’s on the Mall next door.

They’ve reportedly laid $1 million on the line for the State and $525,000 for Harvey’s. Plus, they’ll need funds to renovate the property — one goal of the family is to make the theater accessible for people with disabilities.

The Carmichaels came out of a family business, GT Independence, a Sturgis-based national financial management service company that specializes in self-directed long-term care for people with disabilities.

Holly Carmichael has been Chief Operating Officer and, from 2021 to early 2025, CEO of GT. Her brother-in-law, John Carmichael, who was also mayor of Sturgis, has been GT’s President and is now CEO. In 2021, radio station WTHD reported that GT manages over $350 million in Medicaid funds and serves over 22,000 people in 12 states.

Watershed Voice reported Oct. 6 that GT joined with an investment partner, H.I.G. Capital, with the Carmichael family remaining “a significant stakeholder.”

“Safe… enough”

Dan and Holly took me onto the stage and backstage.

Nearly a century of entertainers trod (danced, rocked, joked) on that old wood. There’s still the outline of the trap doors where magicians would “make baby elephants appear and disappear,” Holly says. It could be fun to get that working, she says. But it was sealed long ago to make sure live acts didn’t unintentionally fall below.

A shuttered balcony, hidden from the audience’s view, overlooks the stage on the left wall. Stephanie Hinman, Executive Director of now-former owners the Hinman Company, watched Primus from there, Dan says.

Backstage are numbered doors to enough dressing rooms for a vaudeville troupe. The green room has a painted wall — the guy who painted it in the 1990s was fired the same day after painting over autographs from entertainers dating back to 1927.

Maybe they can find a gentle paint remover to uncover that history, Dan and Holly speculate, but that’s another item lower on their list.

Holly opens a door to a dusty cubbyhole to show the old organ and ancient hydraulic hoses. The organ and its player would rise to the stage, to play music for silent films and audience sing-alongs.

Back on stage, we inspect the large black bank of old light switches, 1927 technology, looking like it’s from Frankenstein’s lab. Some still work — Holly pulls the handle down on an old knife switch with a satisfying metallic “CHUNK.”

A nearby metal ladder attached to the rear wall goes up a couple of stories into darkness. Rope rigging with heavy sandbags and weights also tower above. Ropes are secured together with electrical tape.

Holly looks up the ropes. “These are operational and…” she hesitates, “safe… enough.”

Yes, but in every murder mystery that takes place in a theater, sandbags exactly like those eventually come down on someone’s head, we point out.

Dan and Holly will be going over all the issues with the building, making sure it’s safe and operational, they promise.

It’s an old antique that needs improvements that don’t ruin its 1927 aesthetic.

There will need to be some modernization, but the Carmichaels want it to look the way it exists in people’s memories.

“We love this space. I don’t know if you’re human, if you can come in here and not feel how amazing this space is,” Holly says.

Lead Balloon hopes and dreams

The couple bought the State through their recently formed Lead Balloon production company.

Why Lead Balloon?

“Well, it went over like a lead balloon,” Holly says, laughing.

Dan shows a tattoo on his arm of a hot air balloon lifting a ship’s anchor.

“It’s a way of reminding yourself not to get too high, not get too low,” he says.

The image is the logo of Modest Mouse. Dan and Holly had their first date at the State, seeing the band in 2006.

Dan Carmichael is a stand-up comedian who’s worked with Doug Stanhope (he appeared in Stanhope’s 2023 movie “Road Dog”), Bobcat Goldthwait, Tommy Chong, and Todd Barry.

The couple has seen a lot of comedians and bands at the State. The last was comedian Jim Jeffries, who played in October last year. A few weeks later, they were shocked to see the theater close without warning.

They thought, “Hey, what a bummer,” Dan says.

Then they both began speculating, “What if….” Speculation turned into “Hey, we could do that” in repeated conversations.

Dan says, “We reached out to our good local friend Dann Sytsma,” of the Crawlspace Comedy Theater and Kalamazoo Nonprofit Advocacy Coalition, to ask what he knew about the state of the State. Sytsma then linked the Carmichaels up with Stephanie Hinman.

The Hinmans “had a strong vetting process. It wasn’t just going to be anybody that they handed the reins over to,” Holly says.

Then the word came that Hinman property, Harvey’s on the Mall, was also closing. They threw that in the deal. “Harvey’s was a bit of a surprise for us,” she says. The buildings are linked — there’s a literal door backstage at the State that would open up into the restaurant, but it opens up to a wall on the other side.

The Carmichaels have been close-lipped about the price they paid, but WOOD TV revealed that property records showed $1 million for the State Theatre and $525,000 for Harvey’s.

WOOD gave out their secret?

“They did!” Holly says, mock-mad.

So, how are they funding this venture — the upfront cost, and the future cost of renovations?

Dan says, “I’ve got a pretty good hunch about the 49ers next week. So….”

Holly laughs, “He’s not betting to save the theatre. No, I think we expect to fund a lot of it just privately,” she says.

What’s next?

They’ll “explore and do research about what makes the most sense,” in funding the future of the State. There are tax credits on historic buildings, Holly says, “there’s probably a lot of other types of support that we could get. But we’ve got to explore that and kind of figure out, you know, even what may be needed for certain.”

Dan says, “A lot of similar theaters are run by nonprofits, and that’s something that we may explore down the road. But right now our focus is to get the resources into this theater and get it preserved.”

They’re enlisting the help of Wilson Butler Architects, a Boston company that specializes in arts and entertainment spaces.

“Our work will focus on respecting the theatre’s historic character while ensuring it thrives as a cultural hub for generations to come,” Rebecca Durante, of Wilson Butler, says in the Carmichaels’ press release.

Sustainable theater?

How much will it cost to get the theater operational again?

“We’re probably in an eight-figure number,” Holly says.

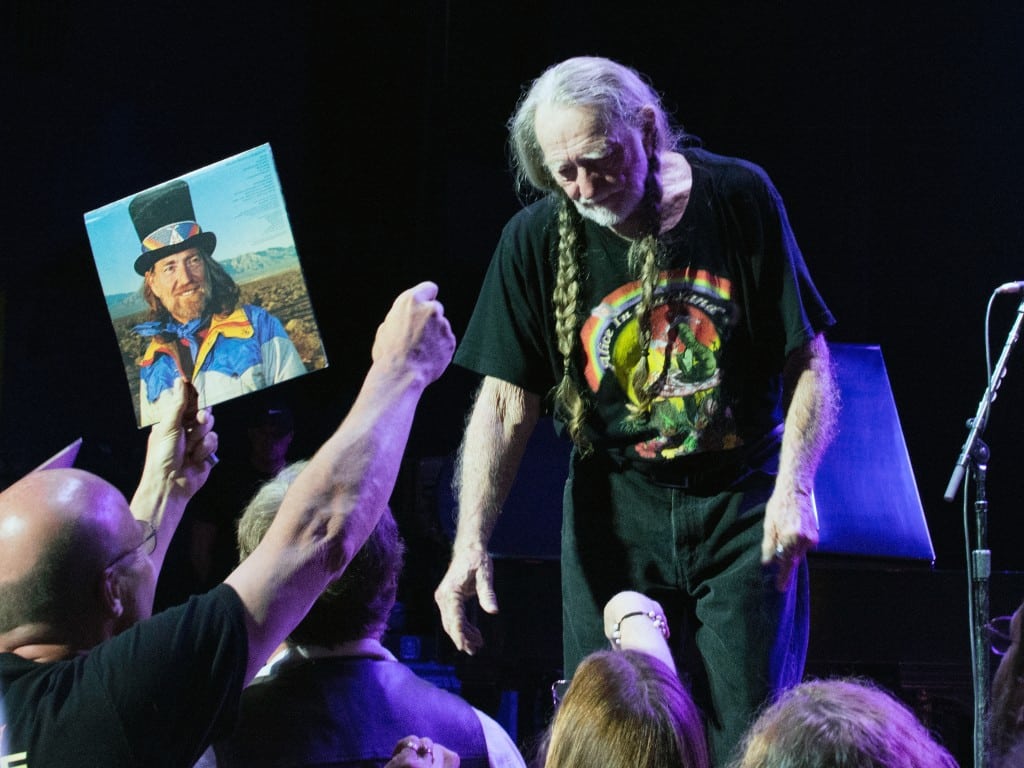

That’s a big investment. Will they be able to stage the shows that’ll pay it off? The State had been, from the 1980s on, known for bringing in mid-sized touring acts that aren’t arena-fillers or small-time bar bands. State acts include up-and-comers like Chappell Roan — who sold out the theater last year, and this year won a Grammy for Best New Artist — or old classics like Willie Nelson, Bob Dylan, Arlo Guthrie, and Buddy Guy, who found a home in the antique setting.

There has been, and will be, competition with downtown venues. Bell’s Eccentric Cafe sometimes brings in acts in that mid-range category. And the upcoming downtown arena, what kind of entertainment will be there?

The Carmichaels don’t want to get too far ahead of themselves, they say.

“We want this to be an artists’ venue,” Dan says. It should be an experience for the audience, and “We want it to be an experience for (acts) as well.”

As for competition, Holly says, “There really is a venue for every type of event” in Kalamazoo.

The couple has contacts in the entertainment industry, “will likely bring on a team” who’ll book shows, Holly says.

They’ll need to find “balance” with the acts they’ll bring to Kalamazoo. “You can have some shows where you do well, and maybe some shows where you don’t,” Holly says.

But first, they have to reopen. They hope to do that in 2027, to celebrate the centennial of the State. But at this point, the Carmichaels aren’t ready to commit to a firm date for when the first act of this new era will be in front of an audience.

“Our first step is focused on restoring and preserving the theatre and modernizing it so it can last the next hundred years. Then comes the business plan to make money,” Holly says.

She adds, “We don’t have any wild-hair dreams that this is going to be a massive money-printing machine.”

Where memories took the stage

It can’t be overstated how ingrained the State Theatre is in Kalamazoo’s cultural memories.

I asked my Facebook friends about their favorite times at the State, and was flooded.

Older generations remembered live acts like the magician Blackstone and big band groups. Craig Vestal says his mother saw Billy Eckstine there, and ’50s gimmick movies like “The Tingler,” “where they put buzzers under the seats to scare people,” he writes.

Second Wave photographer Fran Dwight remembers watching The Beatles’ movies “Help” and “A Hard Day’s Night” in the ’60s. My Gen-X friends were all about bands like Soul Asylum, and some played on the stage at Kalapalooza — a festival of Kalamazoo bands in the early ’90s.

Long ago, my mother told me stories of how she, known as Ruthie Gilkison then, would ride bikes with friends all the way from Austin Lake in the 1940s to see reruns of old monster movies like “King Kong” at the State.

My conservative parents took me to every G-rated Disney movie at the State in the ’70s. In 1984, the teen me rebelled by seeing the angsty punk acoustic trio Violent Femmes, my first concert, at the State.

Between 1992 and 2015, it felt like the theatre was my workplace. As an A&E freelancer for the Kalamazoo Gazette, I reviewed bands and comedians, Marilyn Manson to Ray Charles, Carrot Top to George Carlin, around once a month, sometimes once a week.

I’d pester box office manager JW Ferris for reviewer’s tickets, and he’d crankily suggest I ask the acts’ manager or pr person next time. But he never turned me away. Once, he sat me on a hard marble bench in a theatre alcove, because I was too late in getting reviewer tix for a sold-out BB King show.

“He was a cash guy, he was old-school,” Ferris, 78 and now retired, says of blues great King.

Ask Ferris about his State memories, and he tells of dealing out “$20 grand” in cash to King, and also paying blues singer KoKo Taylor in cash. “I’d give her the money and she’d peel off all these bills, put a bunch in her bra and said, ‘Well, this is for the rest of the band,’ which she meant the bills she still had in her hand.”

Ferris loved the Budweiser Blues Series, where the beer company paid for countless blues acts who played the State. One year, they were auctioning off a guitar signed by all the classic blues acts.

“We had it displayed on the second floor…. I was downstairs in the lobby, and I saw this guy walking down the stairs with the guitar!”

A thief was making off with a piece of State Blues history. Ferris and security took off on foot, chased him down Burdick until he threw the guitar under a car. “We got the guitar back, that was really all we were interested in.”

He remembers getting bands from Seattle before they broke huge, seeing Eddie Vedder of Pearl Jam walking among the audience in the upstairs lobby, no one mobbing him.

“Oh, Marilyn Manson, that was interesting,” he says of the controversial ’90s singer. “We had church groups out picketing in front of the theater.”

Morrissey, a famously high-maintenance singer for The Smiths, “had to have special aroma fragrance candles that we had to search out for him.”

Comedians were much easier, “because they come with a notebook or cards, that’s about all they have to load in.” George Carlin was his favorite, “but he would be gone before the first patron hit the street. He’d finish his show, run out the back door, his car was waiting, and off he’d go into the night.”

Bob Weir of the Grateful Dead brought his band to play a few times, “The basement smelled like marijuana — heh, heh, heh! — long before it was even thought about being legal,” Ferris wryly says.

Of the building, Ferris remembers the “spaghetti wires” of the old phone system and the lack of air conditioning.

He wishes the new owners well and appreciates their promise to make the State accessible for people with disabilities. “It’d be nice if there was a way people could get upstairs,” Ferris says.

Puddles Pity Party

The Carmichaels’ favorite State Theatre memory includes a situation where their daughter couldn’t get up the stairs.

Magdalene was around six when she became a fan of Puddles Pity Party videos.

If you don’t know, Puddles is a tall, sad clown who sings sad versions of pop hits in a melancholy baritone. The deadpan humor of the act got him booted from “America’s Got Talent” (though he did reach the quarterfinals), and he’s been opening for “Weird Al” Yankovic on his latest tour.

Magdalene has a rare genetic disorder and uses a wheelchair, her parents say. “That slow, deep voice was easier for her to follow,” Dan says. “She just kind of fell in love.”

Puddles was coming to play the State in 2018, so the Carmichaels got Magdalene meet-n-greet tickets. But there was disappointment — the meeting with fans was upstairs. They missed it.

Stephanie Hinman, however, took the family aside and took Magdalene backstage to see Puddles. “For 15 minutes or so before the show, he just hung out with her and played games and sang songs,” Dan says. “Her little eyes just exploded, and you could just feel the joy.”

During the show, Puddles interacted with Madalene, who was in the front row. Then the “crowd got into it, and they started feeding into it and interacting with her. She was just on cloud nine.”

Dan continues, “I don’t know, the idea of this theatre not being around to provide that next experience for somebody was just not acceptable.”