Remembering the Block: How Black history and culture inform Kalamazoo’s present

As downtown Kalamazoo transforms, residents are turning to the deep history of Black art, culture, and community on North Burdick Street to ground the present by understanding and respecting the city’s roots.

KALAMAZOO, MI — There was a time when the 300 block of North Burdick Street was alive with art and culture, and a gathering place for people looking for friendly faces.

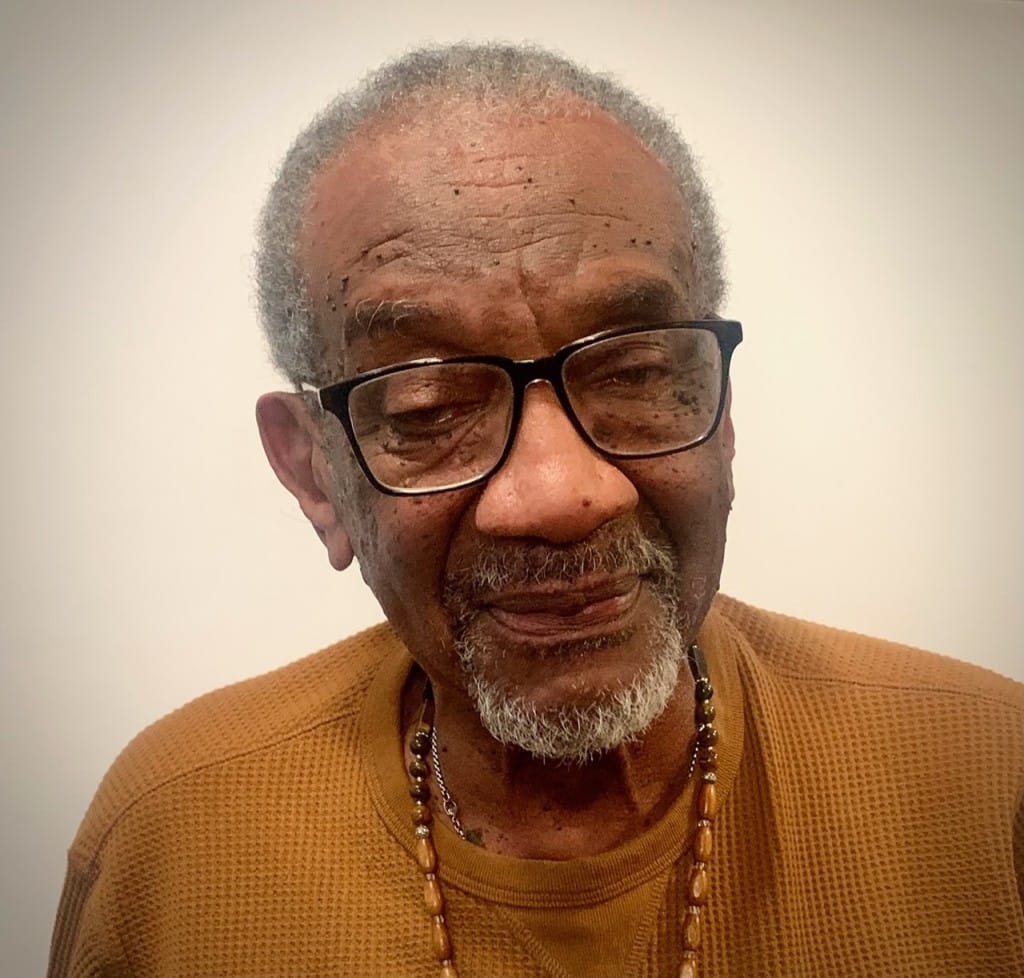

“A lot was going on in the 1980s all over the country,” says local poet and performer Buddy Hannah. “But from a cultural standpoint, from an entertainment standpoint, and just for people gathering and having a good time, we had all that here.”

Hannah was among five speakers to pay homage last week to the history of North Burdick Street during the sixth installment of the Institute of Public Scholarship’s “Remembering the Block” series. Located at 313 N. Burdick St., the Institute has spent this year appreciating the history of the area by hosting spoken-word accounts from people who have researched the history of the area, and those old enough to remember it.

The series is led by Dr. Michelle Johnson, a local historian and educator, as well as the founder and executive director of the Institute of Public Scholarship. Its focus has been on institutions that were significant to the development of Kalamazoo’s African-American community since the early 1900s.

“Our ultimate goal is … to make sure that our stories are not forgotten, that the people are not forgotten,” Johnson says, “and that we continue to lift up the past and use that past to inform our future.”

She says that is especially true as significant changes are happening in parts of downtown Kalamazoo. She mentioned the Kalamazoo Event Center, a 453,000-square-foot sports and entertainment venue that is under construction and set to open less than a half-mile away on West Kalamazoo Avenue.

“And so the Remember the Block series is set on remembering our past,” Johnson says. “And not in any old kind of dusty way, but to be able to create opportunities for us to do interpretive installations for this.”

A home for arts and culture

On Wednesday, Nov. 12, 2025, speakers focused on the development of three establishments that were key to the social and cultural health of African-Americans here: the Douglass Community Center, the Turn Verein Building, and Kalamazoo’s Black Arts and Cultural Center.

“It started 40 years ago in 1987,” Executive Director Janine Seals says of the Black Arts and Cultural Center. “So our 40th year will be next year. It started as a place where artists could come and work and share their work. And kind of get together as Black artists.”

A group of creative individuals came together as the Black Arts & Cultural Committee to shepherd Kalamazoo’s first Black Arts Festival in August of 1986.

“The festival started first,” Seals says. “And then they needed a place for it. So they found an old boxing academy downtown, and they were there for a couple of years. They started there after the festival and then became incorporated as a 501c3 (nonprofit organization) after that.”

The organization initially used space on the second floor of what was the Kalamazoo Boxing Academy. The location was demolished later to make way for what is now part of Kalamazoo Valley Community College’s downtown campus.

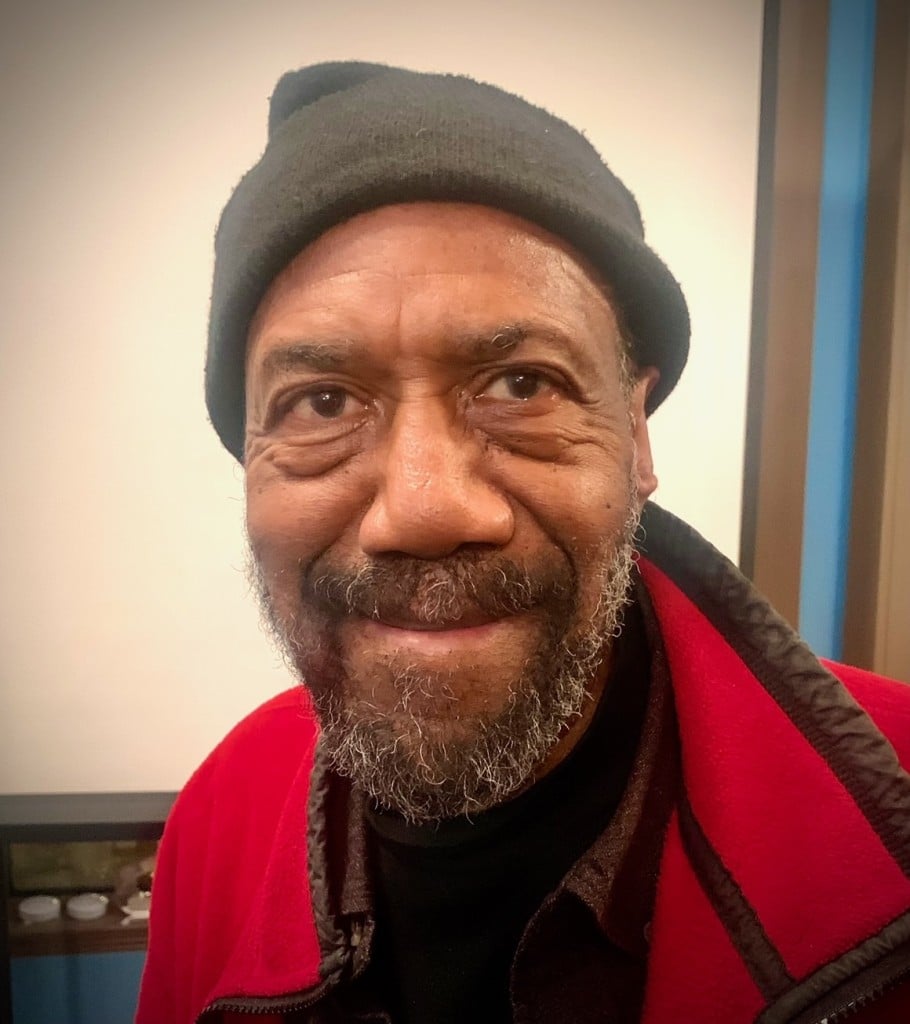

The BACC grew to provide African-Americans a place to create and display works of art in any form, and from a cultural standpoint, “to let people know we were here,” says co-founder James Palmore.

“With the Black Arts & Cultural Center, the ‘arts’ parts of it are kind of obvious, but the word ‘culture?’ Palmore says. “That word culture is basically our essence — who we are. This is a place to come and connect with it for inspiration, encouragement, knowledge, skill-development, and basically the confidence to stand up. To let people know that we are part of the human race. We have to let people know that’s who we are.”

Hannah, who has played a leadership role at the BACC since the late 1980s, remembers it as a place where he was challenged to evolve from being a person who writes poetry to someone who is an actual poet — sharing his work in performances.

Editor’s Note: Please see Buddy Hannah’s poem about Allen Chapel A.M.E., one of the Northside’s oldest churches, in this week’s Poet’s Press.

“We had all kinds of things going on,” he says with a smile.

Executive Director Seals says people should know that the BACC, now at 359 S. Kalamazoo Mall, has programming for adults and children.

“So we’re not just the Black Arts Festival. We do programming, everyday activities, and summer programming,” she says. That includes plays, poetry, dance performances, educational resources, art classes, and cultural events. The BACC also has a large gallery space that allows it to feature the works of a new artist each month. It also continues to collaborate with other organizations.

A turn for the better

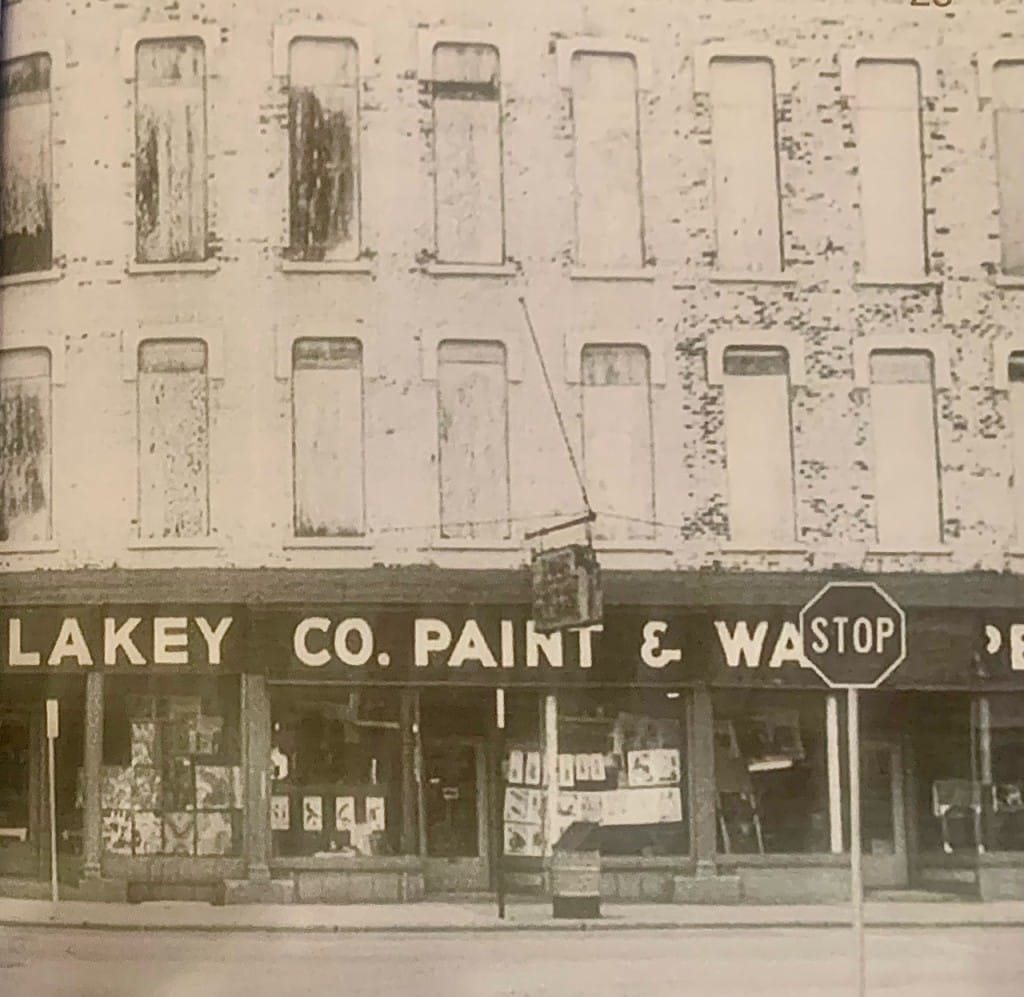

From the late 1880s to the 1920s, the east side of the 200 block of Burdick Street was home to Kalamazoo’s original Turn Verein Building, a place that became a social refuge for Black soldiers and the first large gathering place for Kalamazoo’s Black community.

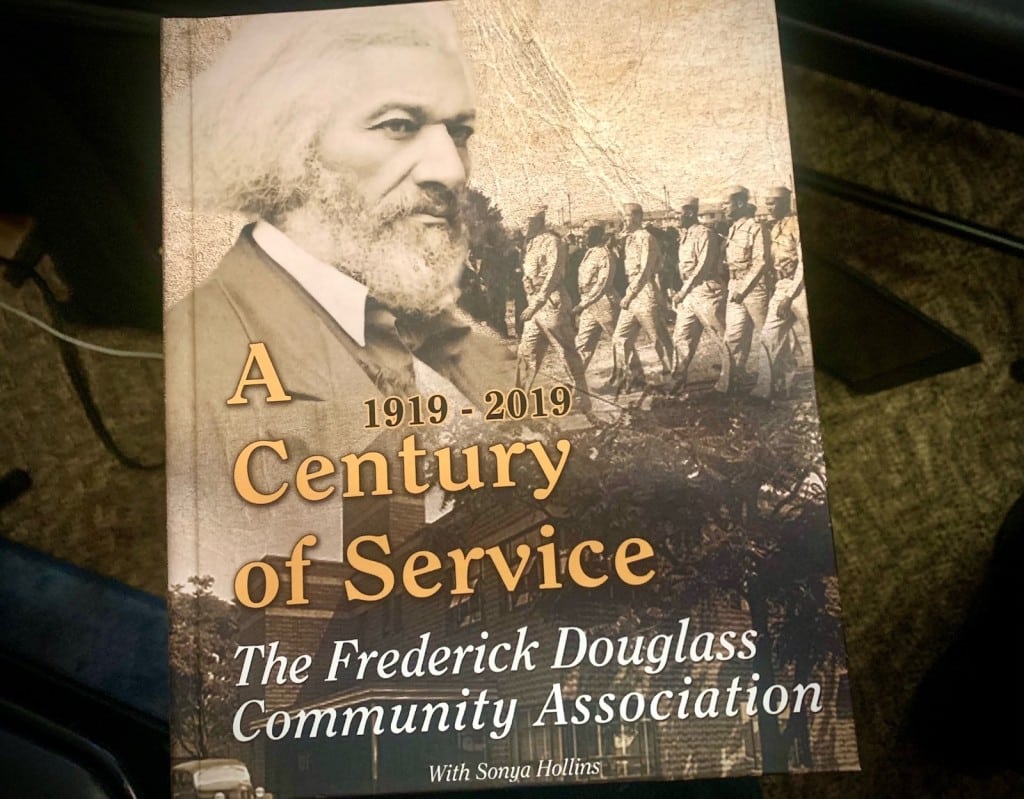

“There was a lot of drama in our community,” Sonya Bernard-Hollins says of the years following World War I (1914-18). That inspired African Americans in Kalamazoo to want to create their own place for events and gatherings. But the effort started in a space created by German immigrants.

“In Michigan, you look at integration and segregation as being in the South,” says Bernard-Hollins, who is editor of Community Voices magazine and the author of “A Century of Service – The Frederick Douglass Community Association.” “There was a lot of segregation here, even in Kalamazoo. If you go back and look at the archives, you will see that they were putting Chinese people in jail because they were not supposed to be in this area. There was a report saying they put two Chinamen in jail because they were out of place.”

Violent racial incidents in 1919 in Chicago, Tulsa, Okla., and other places made for tense relations nationwide, she says.

“They had a huge Ku Klux Klan population here in Kalamazoo,” she says. “We also had the Fort Custer military base in Battle Creek at the same time. Now we put everything together. We have these Black soldiers who are in Battle Creek with nowhere to go. They come to Kalamazoo, which was the big city, on the Suburban, which is like a little inter-urban transit system. And they’re coming around, and there’s nothing for them to do. You’ve got all these Black men standing around with nothing to do.”

She says Black leaders realized they needed to find somewhere for the soldiers to go to avoid trouble. Working with White business and civic leaders, they found the third floor of the Turn Verein Building.

A safe place to socialize

The large, three-story structure (formerly 226 N. Burdick St., running south along what is now the Kalamazoo Mall) was established by German immigrants to serve as a center for their social and recreational activities. It included a dining room, kitchen, stage for musical performances, reception rooms, bowling alley, and a gymnasium. It was one of many such centers established by German immigrants across the United States in the late 1880s.

In Kalamazoo, its third floor became a safe respite place for Black soldiers training at Fort Custer to serve in World War I. As that war ended, the need for a community center for Black people of all ages continued, and the location became the first Douglass Community Center.

At a time when most of Kalamazoo’s Black community lived in various places east of the railroad tracks that cut through Kalamazoo’s central business district, and “white-only” signs barred their access to many places and services, the location provided a place for community members to have dances, host theatre productions, churches meetings, basketball games, and even beauty pageants (where the winner was the young woman who collected the most charitable donations).

Johnson marveled that the German community had a great appreciation for the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863, which essentially ended chattel slavery in the United States. She says an Emancipation Celebration hosted by Black organizers and held at Turn Verein Hall on Aug.1, 1894, included visiting speakers, a concert, and a raft of activities, including bicycle races, foot races, a tug-of-war, and a greasy pole climbing contest.

“This was a popping area,” Bernard-Hollins says of the Northern part of downtown Kalamazoo. From the late 1800s to the 1920s, it was home to any number of shops and businesses operated by German immigrants. In 1941, Douglass built a new home at 231 E. Ransom, where community members continued to host visiting soldiers as well as various programs and community events. In October of 1984, it relocated to its present location at 1000 W. Paterson St.

Holding the line on history

The area of North Burdick Street near Eleanor Street in downtown Kalamazoo has been home to a variety of businesses and organizations that served the entire community. Since the 1970s, they have included Mr. President’s Restaurant & Lounge, the Kalamazoo Boxing Academy, the Nimble Thimble tailoring shop, Flipside Records, Sarkozy’s Bakery, and Bell’s Brewery (which got its start in space on the lower level of Sarkozy’s).

The 313 N. Burdick St. offices of the Institute of Public Scholarship were once the home of Missias Tavern, a “working man’s” bar operated by Greek immigrants from the 1930s until 1977. For many years, it was considered Kalamazoo’s only truly integrated bar and prided itself on being a friendly place for people of all races and ethnicities.

While there appears to be a national movement to rewrite some less-than-proud parts of American history and erase some historical accounts altogether, the effort to preserve African-American history here has been a mission of the Institute of Public Scholarship.

“Our history is rooted in these organizations,” Seals says, “especially the Douglass Community Association and the Black Arts and Cultural Center, where we as artists and we as Black individuals become more proficient at what we do. It is something to say, ‘Hey, this is where I come from. This is the roots.’ And the people who started these organizations are just amazing people that you would never know are here in Kalamazoo. Just average people that created these amazing organizations.”

Knowing our roots

Stacey R. Ledbetter, executive director of the Douglass Community Association, echoed that sentiment, saying, “History is important. It helps us know our roots.”

Knowing where we came from, she says, “helps to cultivate how we want to maintain (ourselves), and forecast for the future.”

While she has been focused on the 300 block of North Burdick, Johnson says, “We understand there are many other blocks that could be the focus in the future. She says the most important thing is for people to recognize the long-standing history Black people have in downtown Kalamazoo.

“People don’t understand that we have these long-standing roots in Michigan and that go in Kalamazoo (back) to the 1860s,” Johnson says. “And so it’s imperative that people know that we were here. But also for our young people to see themselves in this place, to have a sense of belonging in this place, and to know that their ancestors helped to build this place.”