A Way Home — Housing Solutions: This story is part of Southwest Michigan Second Wave’s series on solutions to homelessness and ways to increase affordable housing. It is made possible by a coalition of funders, including the City of Kalamazoo, Kalamazoo County, the ENNA Foundation, and Kalamazoo County Land Bank.

KALAMAZOO, MI – Jeremy Cole has an eye for creating housing that fits people’s needs.

It’s why the Kalamazoo native began buying run-down, unwanted houses here more than 20 years ago — to refurbish and resell them. It’s also why he is now focused on building a cluster of small homes off Cork Street in Kalamazoo’s Westnedge Hill Neighborhood — people need them.

“If you look on the MLS (the Kalamazoo Association of Realtors’ Multiple Listing Service database) right now, there’s probably a half-dozen houses under $100,000,” says Cole, a licensed builder who purchased his first house at age 19. “Out of 330 houses (for sale) in Kalamazoo County, there’s a couple listed for $50,000 that are caving in. They’re falling in. But that’s what you’ve got if you don’t have $200,000 to spend on a house, or if you can’t get approved for something on your budget.”

Cole is looking to offer more options to people of modest means. Working as KZOO BNB, he has acquired 2 acres of undeveloped land adjacent to 132 W. Cork St. with plans to build a “micro” home community. Located just north of Cork Street, between South Rose Street and South Burdick Street, it will include 16 houses, each with 640 square feet of living space.

A portion of the acreage, along the 100 block of Imperial Street, will also have three 1,200- to 1,800-square-foot single-family homes. All will be energy-efficient, quality houses for people who don’t need a large living space and yard.

“If you want something with land, this isn’t it,” Cole says of the micro home community. “You’re not our market. These are for the folks who do want a smaller home.”

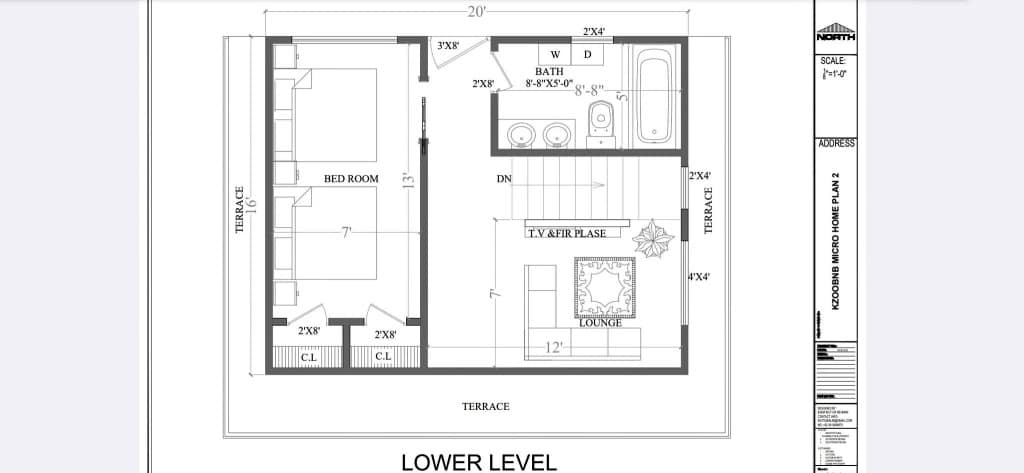

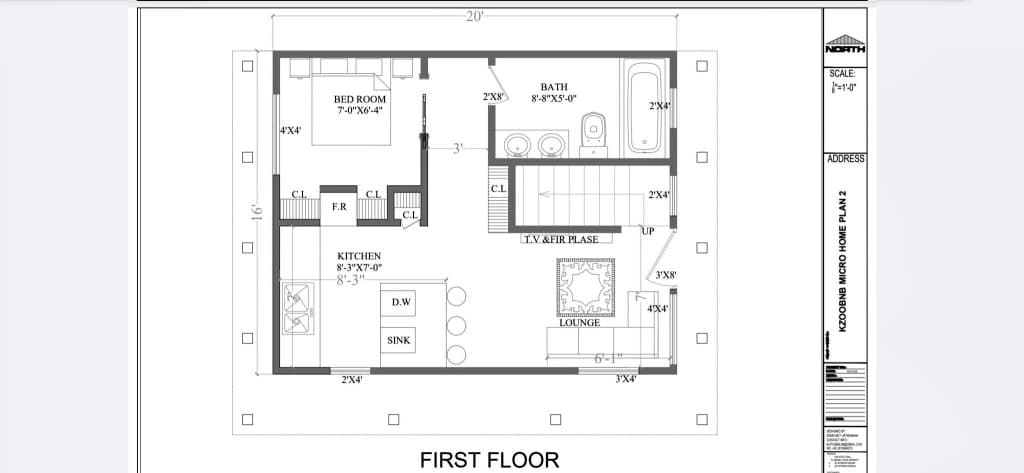

Each house will have two bedrooms and two bathrooms. Each will be built in one of two configurations, depending on the slope of the land in the wooded area. Some will be two-story dwellings with a ground floor and second floor. Others will have a ground-floor level and a lower-level walkout.

“This is called a site-condo development,” says Cole. “Most people are familiar with a regular condo development, where you get one room on Floor 16 and you just own that unit. And lawn care and all of that is taken care of.” In a site-condo development, residents own a free-standing house, the land it sits on, and a driveway or parking spaces. There are also some shared services, such as snow plowing and lawn care.

As currently planned, with adjustments still to be made, the project is expected to cost about $1.5 million. Cole has been meeting with city officials to review plans for such things as sanitary sewer service, water service, property setbacks, and tree retention.

“This is considered a woodland,” Cole says. “The city requirement for a woodland is we have to save 25 percent of the trees. We are not developing 60 percent of the property. So we’re going to save 60 percent of the trees.” Construction is expected to begin in the spring of 2026 and be completed within about 18 months.

Stanley Steppes says Cole is taking his home improvement work to a higher level, describing Cole as an impressive, no-nonsense entrepreneur who is frugal, encourages others, and “sees things differently.”

“He’s a self-starter and extremely optimistic,” says Steppes, who is about three years older, has known Cole since their years at Kalamazoo Central High School, and has worked with Cole on a DIY reality TV show.

Now 42, Steppes was hired last year to be senior brand and marketing officer for the Kalamazoo Community Foundation. He is now its community impact officer. Since August, he has also been the part-owner of KatchaSteak, a pop-up cheesesteak vendor, and Phence & Post, a southern-inspired corporate and special-events catering concept. In 2016, Steppes was a burgeoning documentary film producer who was looking to create content that motivates and inspires people. Cole inspired him.

“There is, of course, resistance (to what he tries to do),” Steppes says, mentioning hurdles that Cole has had to clear as a young African-American man undertaking unique projects. “There are people who say, ‘Why are you doing it this way?’ or ‘You could do it this way,’ or ‘You could partner with this person,’ or ‘You could get this loan.’ But Jeremy — in the most positive way possible — is someone who says, ‘I see the path. I see what needs to be done. And I’m going to do it.’ What’s really amazing about him is that he’s doing it.”

Cole, 39, is a licensed builder who was in his third year at Western Michigan University’s Haworth College of Business en route to a career in banking when he dropped out to focus on real estate investing and development. He says he has never had an interest in building an apartment complex and says building a large housing development is out of his range. But he has always lived in single-family homes and believes people appreciate the feeling of owning their own home. Building micro homes, he says, “is kind of like that middle ground where you can house quite a few people.”

“This is the biggest one we’ve done,” Cole says of the housing projects he has undertaken. “It’s the first one like this in Kalamazoo — where it’s a micro home community. They’re brand new. They already fit within the existing community. And it’s just fun. It’s new. It’s something that hasn’t been done here. And I think people are going to love it.”

While others have built small homes in Kalamazoo, this is expected to be the first small-home community. Cole’s company will be the builder, working with a network of local subcontractors he has cultivated. But Cole’s company does not intend to be a landlord or sell the individual micro homes.

“The idea here is to sell them to one entity and then allow them (that entity) to resell them to the local community,” Cole says. There are organizations such as Kalamazoo Neighborhood Housing Services and the Kalamazoo County Land Bank that have home-buying programs for people who are looking for affordable housing.

Pricing for some of the homes could be structured to attract families with annual household incomes well below the Area Median Income. (For Kalamazoo, the federally recognized AMI for 2025 is $95,800.) That would allow some to move out of rental properties and into their own homes. Cole says the sale price of the micro homes will ultimately be set by the organization that buys the group of homes from him and resells them.

“We tried to do a program like this five-six years ago where we would buy a bulk of houses, resell them to folks, and try to tell them, ‘Hey, please don’t sell this house within five years just to recoup the equity,'” Cole says. “None of them kept the houses. They all sold. They all pocketed $30,000 to $40,000. That wasn’t the intent.”

He estimates that he rehabbed about two dozen homes before the COVID-19 slowdown in 2020 caused him to shift his focus to buying and remodeling houses for short-term rentals. He was able to keep the selling price of the homes he rehabbed low. None sold for more than $120,000.

“I was very naive when I started, ” says Cole, who became interested in home repair work as a teen, helping his father and uncle fix up a house on Kalamazoo’s East Side. He purchased his first house at age 19 and by age 32 (in 2016) had become the subject of social media videos and news reports after buying and reclaiming local houses that no one else wanted.

In February of 2018, his efforts to convert distressed, tax-foreclosed houses in Kalamazoo’s core communities were the subject of a pilot show for the DIY TV Network called “Gritty to Pretty.” Steppes, whose i83 Entertainment company produced that pilot and pursued the idea of making it a reality TV show for HGTV, says Cole has always been driven to work with troubled properties to get families back into them.

“We were buying houses that were going to be demolished and remodeling them and then selling them to folks with the intent that they’d stay in the neighborhood, plant grass, cut their lawns, and kind of improve the area,” Cole says. “But they bought them, extracted the capital out of them, and moved on.”

He says the home-buying program at a nonprofit organization could be structured to stop buyers from reselling quickly by making them forfeit any discounts or incentives they received.

Cole explains that he is not building “tiny” houses. Tiny houses are generally defined as being 400 square feet or less. They have grown in popularity in recent years among people looking to downsize, live more efficiently, and cut some of their housing expenses. But Cole says neighbors worry that tiny homes will bring down adjacent property values. He says that should not be a concern with the small homes he intends to build. Each of his micro homes will be 640 square feet.

“‘Micro’ homes is just the idea of a smaller home,” Cole says. “If you look around Westnedge Hill, there are probably a half-dozen of these micro homes that are within that (640-square-foot) size range that have sold recently or are pending (sale) right now. There is one on Hutchinson that is a little over 500 square feet that just sold. It’s smaller than ours. There’s a couple over here right on Ash Street that have either just sold or are pending now. There’s even a 400-square-foot home on Imperial Street, a few doors down. … We already have this size home in this neighborhood, and just one street over. So it’s nothing different than what’s already here. We’re just, I guess, congregating them all on one new street.”

Of Cole, Steppes says, “He is just that type of person who, I wouldn’t say, looks for opportunities. But when he has an idea for something, he does what makes sense.”

In 2016, Steppes says, Cole had a stock of unwanted properties that he was fixing up and renting. “But then he was also encouraging other people to … take the risk, make the investment in turning these properties around, and it’s going to be better for all of us.”

Cole is very concerned with making sure his new project benefits the community and that he remains approachable to people who live in the surrounding neighborhood. He and his young family live within walking distance of the yet-to-be-named micro homes project, so its residents will be his neighbors. Cole’s home was among the houses that were set to be demolished before he and his family found and remodeled it.

Cole says he learned that neighbors didn’t like the idea of additional vehicle traffic entering and exiting the micro homes property via Imperial Street, a small street that runs east from Rose Street for about a quarter-mile before dead-ending at the wooded acreage in the 100-block of Imperial Street. So plans have changed. All vehicle traffic will access the property via Cork Street, which runs along the south edge of the property. The three new standard-size houses will face Imperial Street.

The micro home community will be an attempt to use an undeveloped – and largely unnoticed — property in the heart of Kalamazoo to provide housing that may allow people to move from renting a house or apartment, into owning an energy-efficient, affordable home.

Cole acquired the undeveloped property this past summer from the resident of an adjacent parcel who had no buyers over the last four years. A zoning ordinance prevents houses, once they are built there, from being used as short-term/vacation rental properties, he says. Questions about how the houses will be used arises based on the growing portfolio of short-term rental properties operated by KZOO BNB.

Cole was focused on buying, refurbishing, and selling dilapidated houses from 2005 until the COVID-19 pandemic struck in 2020. Affected by the COVID slowdown, he pivoted to build new homes and remodel existing homes. Among them are properties used as short-term/vacation rentals. The latest of those are three houses that Cole and company built on an unused 1-acre plot of land on Long Lake in Pavilion Township. Renters have immediate access to a 240-foot beachfront that Cole also created. He bought the properties in 2014 and developed them after the pandemic struck.

“For me, altogether, anything Jeremy announces he’s doing, No. 1, it’s about community,” Steppes says. “He’s never self-serving. And he’s figuring out how to do it on his own. And if you want to come alongside, great. If not, he says I see this as a path that makes sense and I want to move forward.”

Standing on the wooded micro homes property recently, Cole says, “I want to see this as a vibrant area. I want to see kids riding bikes. I want to see people going for walks. One of the things we want to do is put in some sort of walking trails so you can actually experience it. When you’re inside your house looking out that back window, you’re going to feel like you’re in a forest, a woodland, because we are saving so many of the trees. That’s the vibe, that’s the feeling we want to exude, that we want to show, and that we want to see.”