Solutions at home: How Battle Creek leaders are rethinking housing

Battle Creek is reimagining housing — with ideas such as ADUs, cottage courts, and zoning reforms — to ensure affordability and inclusion across income levels.

Editor’s note: This story is part of Southwest Michigan Second Wave’s On the Ground Battle Creek series.

BATTLE CREEK, MI — The greatest economic mobility comes not through work, but friendships that develop organically in neighborhoods where residents of mixed income levels live side by side, says Ryan Kilpatrick, President and CEO of Flywheel Community Development Services, who was the guest speaker at two different public meetings on Tuesday, Sept. 30 in Battle Creek.

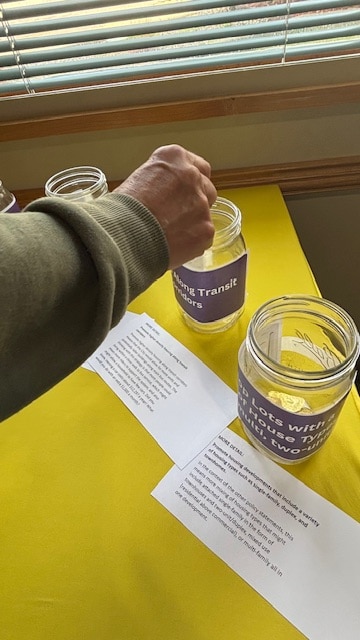

Held at the Kool Family Community Center, the late morning and evening gatherings were hosted by the City of Battle Creek to focus on housing, which city leadership says is among the city’s biggest challenges.

Flywheel’s work “is designed to help your local leadership understand what’s at the root of the housing mismatch and tackle the simple and effective steps required to achieve neighborhoods where everyone can flourish, regardless of age or income,” according to information on its website.

“We work all over the state of Michigan building momentum towards housing goals and pairing that with economic development goals,” Kilpatrick says. “People are drawn to a community because of a job, family, and natural resources. We help communities identify the economic drivers and what in a community is supercharging growth or what the barriers are to a community growing.”

Before the Tuesday meetings, city officials met with a group of 15 local religious leaders who either have housing development plans in the works or are interested in providing housing for marginalised populations through home ownership as a path to building generational wealth. This was the first of several outreach sessions that are being held to gather input from throughout the community about housing as it relates to the City’s Master and Consolidated plans, says Darcy Schmitt, Battle Creek City Planning Supervisor.

Although each of Kilpatrick’s sessions had more than 40 people in attendance, Schmitt says, “We understand that a lot of people are not going to be represented if we just hold these public meetings. Some of the people we’d like to talk to probably won’t be at these meetings either because they don’t feel like they’ll learn anything, or don’t feel comfortable.

“We’re trying to generate a thought process,” she says. “We want to hear from residents if there are certain types of housing that they feel it’s important for the City to focus on.”

The current housing mix in Battle Creek is 70% single-family homes, 15% small multi-unit homes, 11% large multi-unit homes, and 2% manufactured homes, according to Kilpatrick.

In the next five to 10 years, there will be a “massive wave” of Baby Boomers retiring, Kilpatrick says, and they will either stay in their current homes, purchase a second home, or move somewhere else. Those who choose to move into a smaller home will pay more.

A 30-year fixed mortgage rate rose three basis points to 6.39% while the 15-year rate moved up nine basis points to 5.72%, according to Zillow.

Even if they have the financial means, these buyers and their younger counterparts are facing a shortage of homes that will fit their needs, whether they are downsizing or getting into a starter home.

However, the availability of new starter homes and small house construction has fallen from 40% to 10%, a trend that began in 1999, according to Flywheel. The typical starter home is between 700 and 1,250 square feet. The average cost for these types of homes in Michigan is approximately $150,790, as reported by Realtor.com earlier this year.

What’s being built are homes in the $380,000 to $400,000 range.

No matter the size, Kilpatrick says the average cost of a new home is about $200 per square foot. One of the meeting attendees who works in the construction industry says he’s seeing these costs at $300 and up per square foot.

“There’s a mismatch between what we know is true about demographics and what actually gets built,” Kilpatrick says. “I see on a daily basis families coming in making $40,000 or less. The majority who come across my desk are making less than $60,000. Different things are hindering them. Their income needs to be three times the amount of their rent if they’re also paying utilities.

“We need more rental property for the middle income. They’re competing for a scarce supply of rental housing for low-and moderate-income earners. This puts downward pressure on our most vulnerable populations. Homelessness is a housing problem. We don’t have enough places for folks on the margins to catch them before they fall off.”

Possible solutions he shared during the meeting include:

- small cottages on small lots or a cottage courtyard

- attached housing for sale and for rent

- housing dedicated to older adults

- Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs) in existing spaces above a garage or in a basement, or stand-alone structures on the same lot

Depending on the housing option chosen and the cost of constructing that option, monthly rent is anywhere from $500-$1,500 per month, according to Flywheel.

With single-family homes for rent slowly regulated out of communities, Kilpatrick says, “We need to allow existing homes to add a dwelling. That’s exactly what works. The problem wasn’t that we allowed different housing to exist in old family homes, but that we saw that investment flooding out. We need to invest in people and communities like we love them and make a greater investment.”

Cottage courtyards, he says, are a way to bring a lot of houses occupied by Baby Boomers and young families around a shared green space. These houses would not require much square footage and could be located on one or two city lots. Additionally, he says allowing existing homes and new builds to be adaptable for additions also works well.

Schmitt says the city’s current Housing Master Plan serves a lot of different purposes.

“Through the approval of the city’s Planning Commission and the City Commission, I can propose changes to the ordinances for certain types of areas within the city to City Commissioners,” Schmitt says. “We want to know what obstacles in the Zoning Code are preventing the types of housing the city needs and what types of obstacles in general are preventing this from happening.”

Kilpatrick says demand, not zoning or population density, determines property values.

More than half of buyers will accept less green space and square footage to live in walkable, amenity-rich neighborhoods with easy access to parks, trails, restaurants, libraries, and good public schools, he says.

“Between 2 and 3 percent of what we’re seeing is dedicated to neighborhoods like this. If 53 percent want it and only 2 percent can get it, prices go up.”

Home Economics 101

The average age of residents in Battle Creek is 37.5 years old, with 33 percent of the city’s population expected to retire in the next 10 years.

“When a person retires and decides to stay in their current home, local employers are going to have to hire new workers to replace the Baby Boomers,” Kilpatrick says. “They will be hiring younger and newer people into the community, and they will need a place to live. We need more housing to accommodate that shift in the workforce.”

He cites negligible increases in the City’s population. The U.S. Census Bureau estimated the population of Battle Creek to be 52,205 as of July 1, 2024. This figure represents a 1.0% decrease from the April 1, 2020, estimate-based population of 52,754.

“The city needs new housing. You don’t want people to move out for newer workers to move in,” Kilpatrick says.

An influx of these newer workers is anticipated as Ford Motor Co.’s new BlueOval Battery Park in Marshall begins operations. Between 1,840 and 3,740 workers employed there will lead to new households in the area.

“An estimated 900-2,760 new Battle Creek households will be needed,” according to Flywheel data. “This breaks down into 550-1,690 new renter households and between 350-1,070 owner households.”

About 60 percent of Battle Creek residents are homeowners, and about 40 percent are renters. The current housing demand is about 1,540 for households making $238,000 annually, with the rental demand being about 2,800 rental units for households making $60,000 or more.

The median household income in Battle Creek, MI, was $51,699 in 2023, according to the U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts. This figure represents the average income for households in Battle Creek during the 2019-2023 period and shows a 4.06% increase from the previous year’s median of $49,684, as reported by Data USA and U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts.

Kilpatrick says solutions to the housing challenges facing Battle Creek include:

- Creating a regulatory environment that supports much greater housing choice in the market,

- Development incentives that allow some new housing to be available and affordable to the local workforce

- Impact capital to fill financing gaps.

Starting to flee the nest

‘After an 8-year trend, which found young adults unable to move out of their parents’ homes because they couldn’t afford to, the trend shifted in 2022, with some of them able to move, but still struggling because they didn’t have enough money for a starter home,” Kilpatrick says.

Pew Research Center data show that about 36% of women and 48% of men ages 18-34 lived with their families in 1940. Young people started moving out mid-century as they became more economically independent, and by 1960, only 24% of young adults, total — men and women — were living with mom and dad. But that number has been rising ever since, and in 2014, the number of young women living with their parents eclipsed that of the 1940s — albeit by less than a percentage point. And last year, 43% of young men were living at home, which is the highest rate since 1940.

“Kids not moving out is not adding to the population. But they are adding to the housing demand,” Kilpatrick says.

What they’re demanding is housing they can afford.

“In most communities, there’s a great discrepancy between what people can afford and what housing costs,” Kilpatrick says.

This is especially true for young adults who are just beginning their careers and are looking for a starter home or other types of affordable housing. A general guideline is to spend no more than 30% of your gross monthly income on housing costs (rent or mortgage), according to Freddie Mac.

“Younger generations are actively seeking and utilizing affordable housing options as a result of high housing costs, including creative solutions like house-hacking, co-buying with friends or family, moving to more affordable rural or secondary markets, or even embracing renting as a lasting choice rather than a temporary step to ownership,” according to several media reports.

“They are exploring unique housing types like tiny homes and shipping container homes, relocating for remote work, and taking advantage of incentives like those for first-time buyers or lower interest rates from builders.”

When people hear “affordable” as it relates to housing, Kilpatrick says they assume that it refers to Section 8 housing or deeply low-income housing.

“What it means is that it’s affordable to the person living in it. If you’re living in a place that’s not affordable and you’re spending more than 30 percent of your income, it makes it harder to afford other costs like childcare or recreational opportunities.”

The current state on the ground in the United States is that you don’t just build housing for housing’s sake, he says.

“You build to create a sense of community. Most people are drawn to a sense of belonging. At some point, they’re looking for community and connectivity. They want to be tightly woven in the community. You want to build that place for them.”