Neighborhoods Inc. of Battle Creek plays a key role in unlocking housing for the justice-involved

A new state-funded program in Calhoun and St. Joseph counties helps justice-involved individuals secure stable housing through landlord partnerships and financial incentives.

Editor’s note: This story is part of Southwest Michigan Second Wave’s On the Ground Calhoun County series.

The keys to unlocking a new lease on life for individuals in the criminal justice system will include safe and affordable housing in Calhoun and St. Joseph counties.

In July, the Michigan Department of Labor and Economic Opportunity (LEO) announced that the Housing Access for Justice-Involved Individuals pilot program was awarding grants to support residents who the criminal legal system has impacted in finding and obtaining housing. Neighborhoods Inc. Battle Creek is one of two organizations in the state of Michigan to receive a grant valued at $390,817. The other grant, for $279,183, was awarded to the Ann Arbor Housing Development Corp.

“Under this grant, we will be able to provide a landlord sign-on bonus or incentive of a one-time payment,” says Whitney Wardell, President and CEO of NIBC. “The grant will also provide some rental assistance and case management to justice-involved individuals, advocate for those involved in the justice system, and advocate to landlords about why they should work with these individuals as they re-enter society or work through justice issues.”

In her program description detailing NIBC’s plans for use of its grant funds, Wardell says, “We will provide financial support and incentives to increase housing access and the number of landlords who rent to justice-involved individuals for Calhoun and St. Joseph Counties, with a focus on rural landlords.”

NIBC is home to a Housing Assessment and Resource Agency (HARA), which enables NIBC to provide services to house the unhoused in Calhoun and St. Joseph counties. Each of Michigan’s 83 counties has a HARA, which “provides centralized intake and housing assessment, thereby assuring a comprehensive communitywide service and housing delivery system.”

Wardell says NIBC’s HARA in St. Joseph includes the villages of Constantine and White Pigeon. That county’s HARA operations came under NIBC after conversations between Wardell and representatives of the Michigan State Housing Development Authority (MSHDA), who expressed concerns about what had been going on in St. Joseph County. In an earlier story, Wardell declined to go into specifics.

The Housing Access pilot program aims to provide housing assistance and placement to low-income individuals with barriers to stable housing, particularly those with a criminal record, according to a press release from LEO.

“It will also increase the number of landlords in the selected areas who are willing to rent to these individuals through targeted education and incentives.”

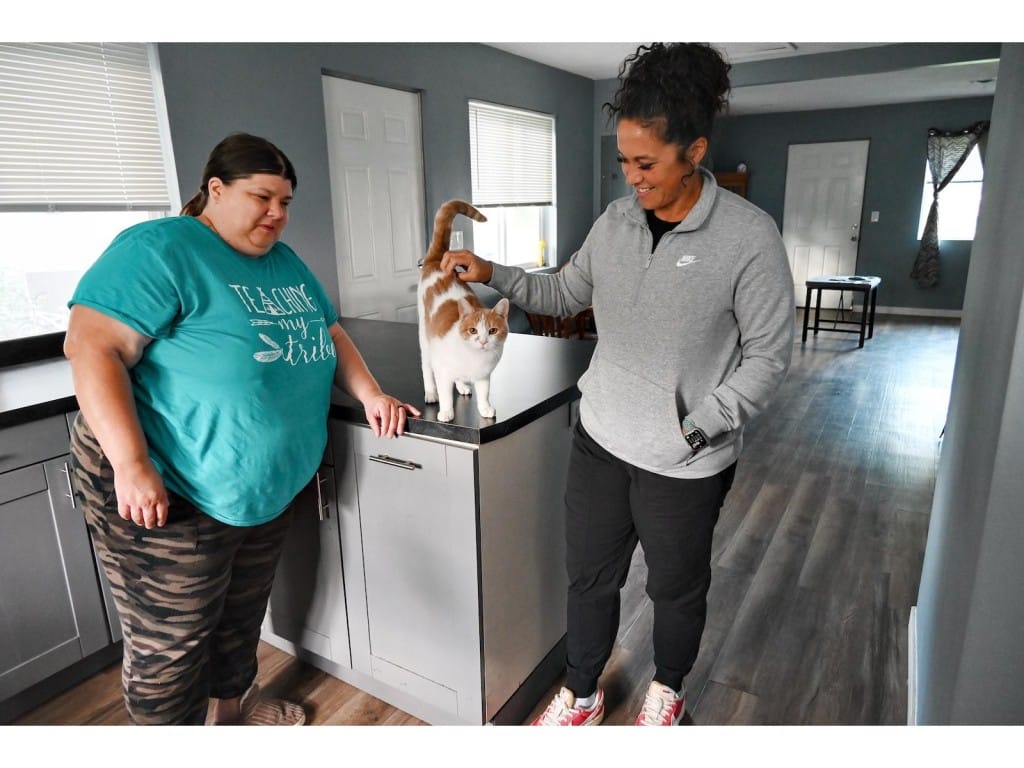

Bre Johnson, who co-owns MBJ Properties with her husband, Mike, says they have a longstanding relationship with NIBC.

“We often go to Whitney first to take care of their people,” Johnson says.

Of the 48 units MBJ owns, which include duplexes, fourplexes, and single-family homes, about 40 percent are rented to NIBC clients. The majority of these units are located on 22nd, 23rd, and 24th streets in Battle Creek, with a few being Section 8 housing.

Four of these units are being renovated, and the remainder are full,” Johnson says. “We’re on the lower end compared to what other landlords are charging.”

But, this does not come at the expense of creating quality, attractive units that include hardwood floors and newer kitchens and bathrooms, she says.

“We’re all about giving people chances and helping people out. A lot of times, the people Whitney brings to us struggle with housing,” Johnson says. “As long as they stay in good touch with me, we are willing to work with them. We all make mistakes and deserve second chances.”

Wardell says NIBC already works with justice-involved individuals to find them housing.

“None of our programs that we offer here will prohibit anyone from accessing our resources,” she says.

Before the program’s official August 1 start date, Wardell says NIBC already had eight people on a waiting list. In the lead-up, she created intake worksheets for clients and landlords.

“We are good and ready to go,” she says.

Unlocking opportunity and second chances

The majority of justice-involved individuals are currently experiencing homelessness. Wardell says some of them could be “staying in shelters or rehab program houses like K-PEP.”

Michigan currently has a recidivism rate measured at 21%, the lowest rate ever recorded by the state, according to the LEO press release. The rate measures those who are three years from their parole date and records how many individuals have reoffended and returned to prison within that timeframe.

A recent report from the Michigan Department of Corrections shows a 79% success rate of those paroled not returning to prison. The housing pilot is one example that showcases how the state is committed to lowering the recidivism rate even further through targeted support for justice-involved individuals.

“The grant program also supports the recommendations of the Michigan Poverty Task Force, whose goal is to remove barriers to economic mobility and lower costs for struggling Michiganders,” says the press release.

Incentives offered by NIBC include a one-time sign-on bonus, access to a risk mitigation fund, first month’s rent and security deposit, and emergency rental assistance. The program will also include education for both landlords and tenants on fair housing practices, debunking myths related to justice-involved individuals and housing readiness. The program will connect tenants to other available resources in the community and provide 12 months of follow-up services to ensure a successful housing placement.

Johnson says she had extensive conversations with Wardell about the Housing Access program. Future tenants will still have to go through an application process and show proof of income, “so that a couple of months in, we’re not having to deal with an eviction,” she says. “We are providing two units right out of the gate for them.”

While there have been issues at times with NIBC client-tenants, Johnson says she always communicates with Wardell about what’s happening as a way to address various areas of concern.

“It’s a low percentage compared to what she’s given to us as tenants,” Johnson says of instances where the landlord-tenant relationship has been severed.

Strong and ongoing communication as a landlord is key. Johnson says she and other landlords have conversations that include alerting each other to tenants who may not have good track records.

“It can be work at times, and you have to have good open communication and stay on people. I always tell tenants, ‘If you’re struggling and need an extra five or 10 days, we can work it out.’ These people are lower-income and living paycheck to paycheck. We need to continue to provide housing for them.”

Landlords, Johnson says, have to be willing to take the risk for these tenants, but they don’t want that extra work.

“Working with NIBC has been phenomenal for us,” she says. “When their clients walk into their new home, they are usually ecstatic, super-appreciative, and thankful. It’s good to be able to help people who are putting forth the effort to improve their circumstances.”

Wardell says she is hoping to develop relationships with other landlords to meet the increasing demand for safe and affordable housing for the demographics served by NIBC, which includes the justice-involved.

“If there are landlords reading this, I’m asking that they become open and giving, not just to our justice-involved but to all those who deserve this opportunity,” she says. “Safe, affordable, accessible housing is a necessity, not a luxury.”