Editor’s Note: This story was written before the recent death of a Kalamazoo 17-year-old. Two teenagers were arrested in connection with that death.

The Voices of Youth Kalamazoo program is a collaboration between Southwest Michigan Second Wave and KYD Network, funded by the Stryker Johnston Foundation.

One 13-year-old boy says there’s a good reason to fire a gun into someone’s house.

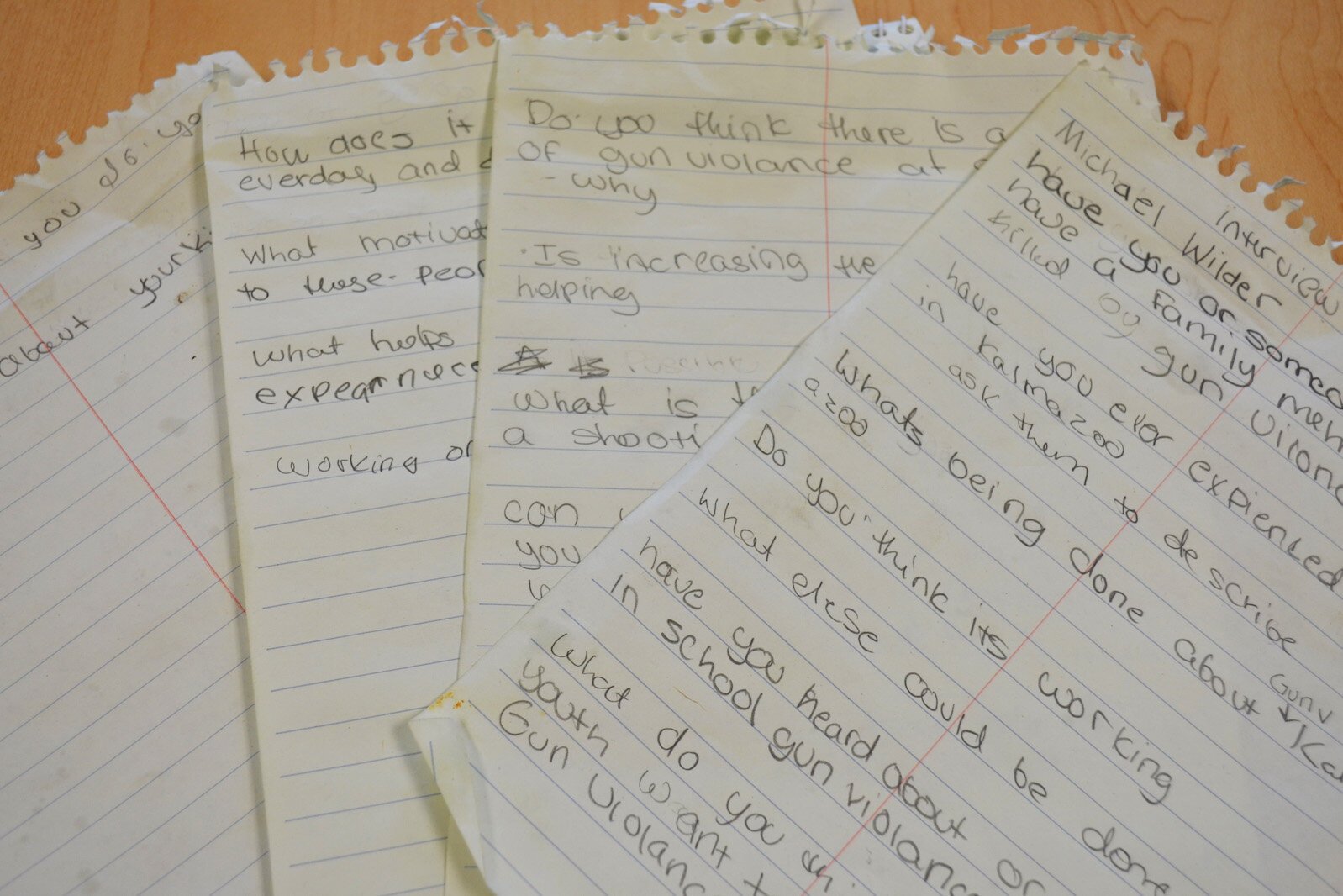

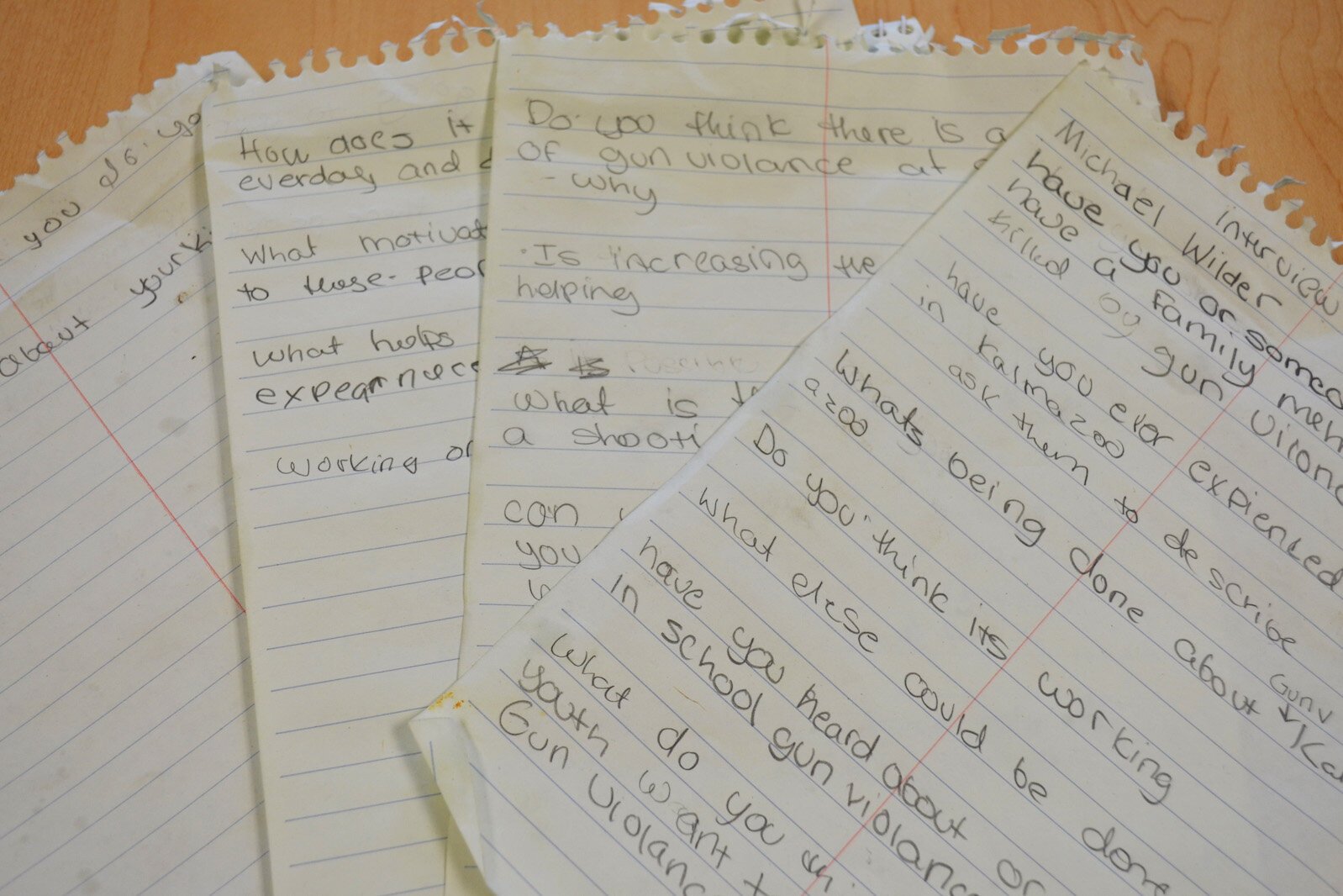

“That shocked me to death,” says Michael Wilder, recalling his conversation with that teen from a few weeks ago. Wilder is the coordinator of the city of Kalamazoo’s Group Violence Intervention Program, which aims to stop gun violence.

His rationale for why it’s OK to shoot?

“He said to me, ‘Well, it’s the dude’s fault.’ I asked, ‘Whose fault?’ And he said, ‘The person who lived in the house who did something that made these people mad enough to come shoot the house up. It’s his fault.’” The teen went on to say, “And if anybody gets hit in the house, it’s that person’s fault.’”

Gun violence, which seems to be featured every night on the news, has adults worried and also some young people who are simply trying to go to school seeking to avoid it.

“I mean, yeah,” says Solomon Thrash, 19, of Kalamazoo. “I see it on the news and I see what happens at schools. It could make me scared, yeah.”

But does the fear of gun violence change the way he does things?

“I wouldn’t say so,” says Thrash, who attends Kalamazoo Valley Community College. “I never really had a fear of guns in my personal life. I know it’s probably around a lot of people though, you know.”

Keylin Tilman, 14, a freshman at Kalamazoo Central High School, says it seems to him that gun violence is on the rise. He says his family is concerned about it, and he worries about his family.

“I mean, not me personally, but more like the safety of my family.”

He says his mother has responded by not wanting him to go “in different areas.” And, he admits, that, sometimes when he goes places, “there’s a fear in the back of my head that it (shootings) could happen.”

Firearms violence falling

While concerns about violence persist, David Boysen, Chief of the Kalamazoo Department of Public Safety, says the number of assaults with firearms in the city of Kalamazoo are actually down 15 percent compared to last year.

Assault with firearms is down – whether someone was shot and killed or whether they were shot and survived. Comparing this time of year to the same time last year, there were 390 firearm assaults in 2021, Boysen says. There have been 332 incidents this year.

“We’re trending way better than last year,” he says.

Boysen says the number of killings (homicides) is also down thus far this year. There have been nine homicides this year, compared to 13 last year. All involved guns. And overall, violent crimes – which include aggravated assault, robbery, and murder – are down 10 percent compared to last year.

Taken separately, aggravated assault (attacks in which someone is seriously injured), is down 16 percent, according to Boysen.

Of the shootings, he says, “The majority of the shootings are group involved, where groups are going back and forth.”

That means the shooters usually know one another and the shootings involve someone from one group trying to get revenge on someone from another group. He says the number of shootings rose in 2020 when COVID-19 caused many events to be canceled and there were not as many organized events for young people.

Shootings continued to increase in 2021, but are now declining, according to Boysen, as law enforcement is going back to working with the juvenile court system, social service organizations such as the Urban Alliance, and outreach efforts such as the Group Violence Intervention Program. That partnership was in place before the pandemic.

“All of us are working together to address this,” he says. “(Those efforts are) starting to take hold again and we’re getting back to pre-pandemic numbers. There is this notion that gun violence has increased, but in actuality, it’s trending in a positive direction.”

Donald Webster, chief of campus safety for Kalamazoo Public Schools, says people are “keenly aware” of gun violence at schools because there have been incidents in many other communities involving children. But he says there have also been incidents at malls, stores, and other places.

“I tell people this all the time,” Webster says, “…The safest place to be is in the schools.”

As with most school districts, there are fights between students in Kalamazoo Public Schools, but Webster says there have not been any shootings or stabbings. Enrollment stands at about 12,100 students, including about 1,700 students at Loy Norrix High School and 1,700 at Kalamazoo Central High School. KPS has about 24 school buildings, serving kindergarten through 12th-grade. Campus Security works to protect them all.

Concern about after school events

Still, Gavin Newsome, a freshman at Kalamazoo Central, says he worries about gun violence sometimes. “Not all the time though,” he says. But being worried that something might happen makes him not want to go to some social events.

“Sometimes like the football games,” Newsome says. “Football games, usually, that’s when most of the stuff will happen when it comes to (fears that there may be) gun violence. So that’s when I will decide that sometimes I may not want to go.”

Going to school events is part of the school experience, Webster says. “We want all of our students who wish to attend these events to feel comfortable doing so, knowing that there is a great deal of planning that occurs behind the scenes to make it an enjoyable and safe experience.”

Webster says Kalamazoo Public Schools is ahead of many school districts when it comes to security. It has added exterior public announcement speakers that allow the schools to communicate with everyone outside. It uses weapon detectors, has a visitors’ management system, has increased the number of campus safety officers, and stays in contact with area police, so administrators know when there’s a problem with someone that could end up at one of the schools.

He says he thinks those things are working extremely well.

“I think the things that we have put in place have addressed the threats that have come to our buildings,” he says. “I think that the things we have put in place have provided a safe environment for our social events, such as basketball games and football games. I think our partnership with our local law enforcement has allowed us the ability to address threats that our students, staff and our visitors don’t see. We work 24 hours a day to make sure that the schools are a safe environment.”

How to stop gun violence?

Wilder, of the city’s Group Violence Intervention Program, says he doesn’t understand the thinking that has young men shooting into homes to try to get even with one another. He says, “Shooting houses where you can hit someone’s little brother, little sister, someone’s mother, someone’s father, that’s crazy.”

He asks, “What is our youth going through that they believe that?”

The Group Violence Intervention Program tries to stop gun violence by figuring out who is involved and explaining the possible deadly outcomes to them. It also tries to steer those involved onto a path toward education or employment.

Wilder says he can connect with troubled young people because he was one of them. The 50-year-old was born and raised in Chicago. He says he once sold drugs and he lived a gangster life during his younger years. During that time, he was sent to prison three times. But he got out and turned his life around.

His day usually starts with him getting a list of suspected shooters from the police – young people they suspect were involved in recent shootings. The police tell them that, if they catch them with a gun, they will face serious criminal charges. The suspects are told they are being watched and the police are prepared to arrest them or any other family members or friends.

The police ask Wilder to offer them alternatives – such as going back to school or finding a job. He says he tells them, “I’m here to offer you a way out. If you follow me, I can make sure you won’t be in any trouble anymore. But if you don’t follow me, what he (a police officer) said, is waiting for you.”

When Wilder talks to young people who carry a gun, he says he asks them what’s their favorite subject in school.

“You’ll be surprised when one of those people looks at me and says, ‘Math,’” he says. “But yet they’re shooting at people and throwing their lives away – making these callous, irresponsible decisions.”

Wilder says they’re intelligent if math is their favorite subject. But a lot of times, they forget that they’re intelligent because they’ve been getting suspended from school since second grade.”

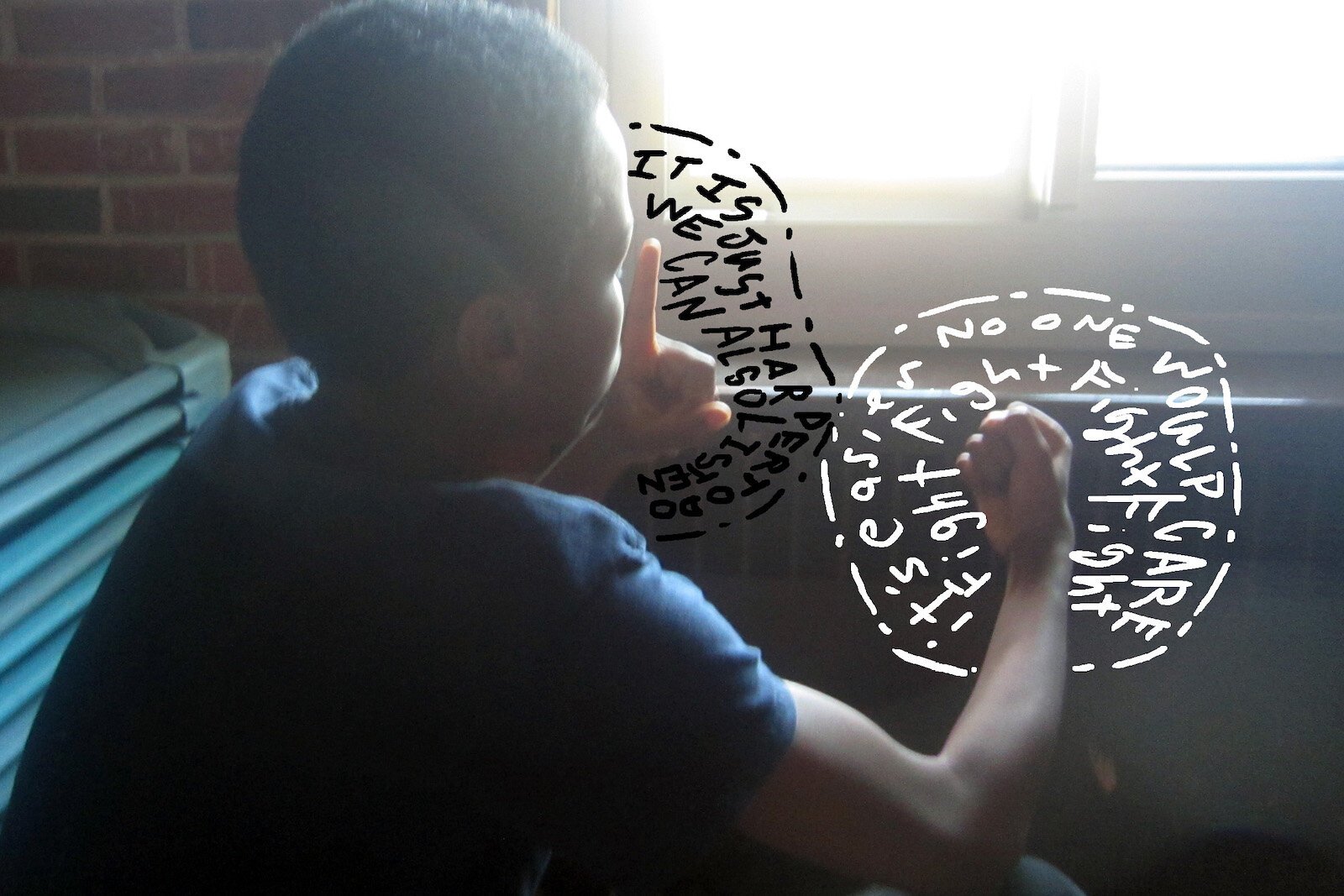

“They resent authority since second grade. They won’t do what the teachers say. They get suspended. They get kicked out. And people forget. The teachers forget they’re smart. The parents forget they’re smart. Because they’re so busy being bad. And so, I remind them that they’re smart. I remind them that they’re talented. I remind them that they’re loved.”

He says almost everybody has someone who loves them. He shows love by letting them know he cares about them, by telling them he cares about them, and by telling them he will do anything he can to help them, even if that’s only picking them up to go for a ride in his car when they have nothing else to do.

In the Kalamazoo Public Schools, security people are behind the scenes keeping watch on social media traffic, on people who have caused problems in the past, and those among their students who may have a “beef” with someone else.

“We don’t let them into games,” says Webster.

When asked what can be done about gun violence, Webster, who is a former deputy chief of the Kalamazoo Department of Public Safety, suggests parents help students develop a sense of awareness regarding all safety issues. “As we know, acts of violence can occur anywhere.”

He says one step in stopping gun violence in schools is addressing gun laws.

“Students, parents, and school personnel can push for gun reform,” he says, “by speaking up, organizing, educating others, writing to your local legislators, and voting.”

Regina Kibezi, 15, is a sophomore at Loy Norrix High School. She was a participant in the Fall 2022 Voices of Youth Kalamazoo program that took place in October. It is her second time attending.