Kalamazoo’s first Tiny Home: a three-decade long dream in the making

Could you live in a 230-square-foot house? Ben Brown wants to and is looking forward to the completion of his Tiny House.

Well before simplicity and downsizing were in vogue, Ben Brown had a core conviction – a drawing down into what he calls his farmer-parents’ “ethos for caring for creation.” For three decades, Brown has been on a quest for affordable, sustainable housing that leaves the smallest ecological footprint possible. And his tenacity has finally paid off. By year’s end, in partnership with Habitat for Humanity and with support from the City of Kalamazoo, Brown will own and occupy the first legal, permanently constructed Tiny Home in Kalamazoo–230 square feet of Tiny, to be exact.

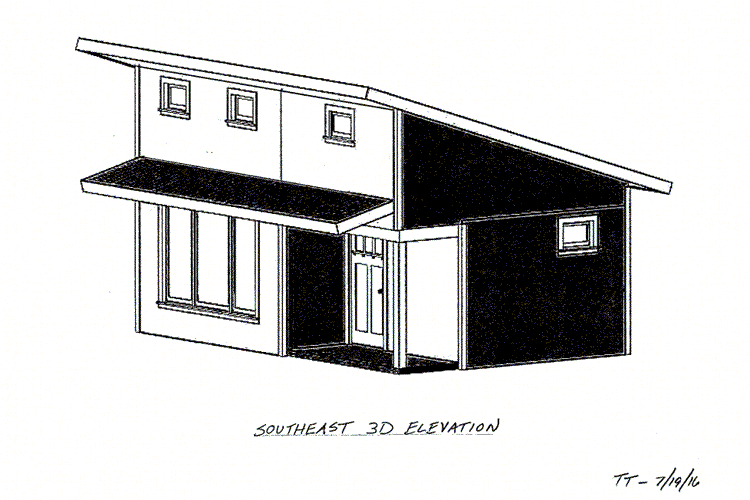

To fit an entire living space into the equivalent of about two parking spaces requires a lot of creativity and lots of planning. Every inch of Brown’s home, currently under construction in Kalamazoo’s Eastside Neighborhood, is arranged with efficiency in mind.

The Tiny Home is situated near the back of a corner, double lot, while the rest of the lot is reserved for the food gardens Brown plans to maintain on the property. The garden shed in the backyard is notably only slightly smaller than the home, itself.

Large, lower windows in the home will allow fall, winter, and spring sun to assist in warming the home, while awnings are designed to reduce solar gain in the summer. The great room’s cathedral ceiling rises to a 14-foot height with clerestory windows which will aid in ventilation. Up several stairs on the far end of the great room, will sit a raised office platform, and tucked beneath the platform will be a pull-out, trundle bed.

A wheeled, folding breakfast counter will separate the kitchen and great room. The rolling counter can be parked and integrated into the rest of the kitchen or moved about for other uses. A Hoover-style clothes washer and water extractor will be hidden underneath a sideboard. The washer unit sips water to clean clothes and can reuse 1st or 2nd rinse water to wash the next load of laundry.

To maximize the space, pantry and kitchen storage will reach to the ceiling, and just off of the kitchen will be a wide, all access, pocket door to the barrier-free bathroom.

Brown’s favorite features are the portable, Japanese soaking tub (useful for treating his chronic health issues), the window views of his gardens, and the way that this home will enable him to live out his values and core convictions.

“I’m very concerned about my great nieces and nephews and the next generation and their children,” Brown says. “You shorten their lives by how I live today. And this house and the property–if anything, I want it to help reverse our climate change, our impact… I don’t want to live to consume this planet or their future.”

Timeless, sensible, and practical housing

Brown’s values of simplicity and sustainability were born out of the way he was raised. As a child, growing up on a sustainable farm, Brown says he learned early on that “simplicity really springs from an awareness of relationship to nature–that you don’t take more from the soil than I can put back into it.”

In 1985, at 30 years old, Brown purchased a farm–paid almost entirely in cash from his savings. But within only two short years, he had to sell the farm in order to pay medical bills, incurred when his health deteriorated, following decades of industrial and agricultural chemical exposure. Brown says he was never able to rebuild his savings after that, leaving traditional home or farm ownership unreachable.

Brown is now 61, and for the past 30 years, he has shared living spaces with various friends, family members, and roommates. In his 50s he even experimented living with mostly college-age students in a housing cooperative. He says he’s watched as most of the friends he lived with over the years–and even their children–moved on and upward into home-ownership. Meanwhile, Brown’s own lower income continued to go to landlords or to basic survival and his commitment to avoiding debt.

Brown says it was at the time of his disability and recovery that his priorities around housing were rearranged. “Any housing I lived in needed to be environmentally clean housing, that did not contribute to further destruction of ecosystems and people. I was less concerned about stylish housing. I wanted timeless housing and a residence that would still be sensible and practical 200, even a thousand years from now.”

Habitat: From skepticism to partnership

Brown says that his conversations with Habitat may have begun as long as a decade ago, but over the course of the past several years, those conversations became more serious pleas. Brown began asking Habitat to consider partnering with him to build a tiny home through their program in Kalamazoo.

Tom Tishler is the construction manager for Kalamazoo Valley Habitat for Humanity (KVHH) and he says, that while providing affordable housing has always been a clear part of Habitat’s mission, they were “admittedly a bit skeptical at first.”

Tishler says that after Brown applied and qualified for Habitat’s program, Habitat wrestled with questions regarding a tiny home project. “Were we being drawn into a “fun” or “trendy” project influenced by a national “buzz” about tiny homes? Would a tiny home be a real asset to the owner (and to Habitat) or a limitation, should the home come back as a foreclosure–a burden with little value and future prospects of ownership?”

In the end, Tishler says, “a tiny home did, indeed, fit into our mission of affordable housing and, in fact, would exemplify how far affordability could be taken in both initial cost and long-term operational costs.”

Tishler says that with Brown’s tiny home, they are far exceeding energy codes by building the home to the rigorous Department of Energy Zero Energy Ready Home standard, Energy Star for homes, and the EPA Indoor air plus standard. “Even without renewable energy use,” Tishler says, “this home will be one of the most–if not the most–energy efficient in Kalamazoo.”

As an award-winning Habitat, KVHH has a solid track record for innovation. Just this year, KVHH was awarded a 2016 Housing Innovation Award in the Affordable category by the U.S. Department of Energy. The award recognizes the Habitat-built home on Glendale Boulevard in Kalamazoo that was completed last spring. The award demonstrates that KVHH is, according to the US Department of Energy, “leading a major housing industry transformation to zero energy ready homes.”

Barriers in alternative housing concepts

Tishler says he was surprised when he learned that Kalamazoo does not have a minimum housing square-footage ordinance and that Habitat wouldn’t need to apply for a zoning variance. What Kalamazoo lacks in restrictions on housing size, though, is made up for in their restrictions on build-able lot size. The current city ordinance states that the minimum lot size for building a new home on a vacant parcel is 5,000 square feet.

Kalamazoo City Planner, Rebekah Kik, says the problem with that minimum size is that “the majority of the city has lots a lot smaller.” Kik says, “This usually requires adding a side lot–or even demolishing another home–to build one on a lot that meets these requirements.”

Kik says that they plan to review the existing lot sizes in the city and revisit the setback requirements so that more options could be open to residents–like the flexibility to construct smaller or even Tiny Homes on smaller lots throughout the city. In addition, Kik adds, “We are also exploring the use of Accessory Dwelling Units.”

Accessory Dwelling Units (ADU’s) range from an apartment built above a garage to another dwelling (i.e. a tiny house) built in a backyard. An Accessory Dwelling Unit ordinance would most likely restrict rental properties from adding an ADU and would require that the primary residence is owner-occupied in order to build one.

Kik, an architect by trade, has direct experience with alternative housing models and Tiny Homes. Prior to her position as Kalamazoo’s City Planner, Kik worked for an architectural firm, whose engineers, in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, designed tiny homes, called, Katrina Cottages, as an alternative solution to FEMA trailers.

“The Katrina Cottages presented the opportunity for displaced people to have a real home, one that could be added to over time as they rebuilt their lives. The FEMA trailers were always meant to be a temporary solution. The tiny homes were a way to rebuild,” Kik says.

Brown says he has tried to talk to officials in other cities, who wouldn’t even let him in the door to talk about Tiny Houses. Rebekah Kik’s commitment to not just Brown’s Tiny Home project, but to the larger implication of what this kind of housing option could mean for other Kalamazoo residents, besides himself, is the reason he refers to Kik as not just a “champion” for his project, but as “The Galadriel of Kalamazoo.” (That’s a Lord of the Rings reference, for those not in-the-know, and according to fantasy translators–my kids–it means she is basically awesome.)

The Future

The Tiny Home concept has taken off in wild extremes. Some communities – like Detroit, and Austin – have used tiny homes as a simple, cost-effective solution to homelessness. On the other extreme are wealthy outliers, who are building simplistic, but high-end versions of these homes.

Brown doesn’t think either are wholly representative of Tiny Homes. Instead, he calls Tiny Homes “simply another housing strategy.”

“There are people that are building $200,000 tiny houses and the same size place can be also found for like $10,000,” Brown says.

Habitat does not yet know what the final purchase price of Brown’s Tiny Home will be, but it will not be on either the low or high extreme. In the end, Brown will hold an interest-free mortgage with Habitat, the principal of which will be recycled into future Habitat projects. Like any other home, Brown will have homeowner’s insurance and an appraisal on the home, as part of the underwriting process.

Tishler says, “Possibly the biggest obstacle we may face will be the appraisal. We have contacted local appraisers that said they don’t know how they would appraise the tiny home because there are no comparable homes to base the appraisal on. We’ll see how it works out when our mortgage underwriter begins the closing process.”

Brown says he hopes that his decades of perseverance go beyond seeing his own personal dream realized and that his hard work will have helped to pave the way for others who are looking for less-than-traditional options when it comes to housing.

“Everyone I’ve talked to who has worked and built a tiny house that they’re living in has said it was absolutely the best expenditure of money that they have ever spent in their entire lives because it freed them from mortgages, it freed them from this and that. And once they had disposable income, they could do things that no one could have ever imagined people would do.”

Brown’s home is scheduled for completion near the end of the year. Habitat plans to open the home for the public to view, upon completion.

Kathi Valeii is a freelance writer, living in Kalamazoo. You can find her at her website, kathivaleii.com.

Photos courtesy of Habitat for Humanity and Ben Brown